Introduction

Recently, the Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (US agencies) issued a proposal to increase capital requirements for all banks with total assets greater than $100 billion. This proposal is directly based on a revised capital framework that was agreed to by a group of global bank regulators, known as the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), in 2017. Importantly, the U.S. agencies are all active members of the BCBS and each played an important role in crafting the 2017 framework.

It has been estimated that the proposal will increase large bank capital requirements by 20 percent or more. In this Capital Insights post, we will focus on one specific aspect of the heightened requirements – the negative impact these new capital rules would have on small business lending. Further, we will discuss how the U.S. capital proposal is out of step with proposals made by European Union (EU) and United Kingdom (UK) bank regulators to implement the 2017 Basel framework.

Risk Weights for Investment Grade Corporate Loans

Today, all corporate loans receive a “risk weight” of 100 percent. This means that if a bank has a capital requirement of, say, 10 percent, that bank would need to use $10 of equity capital to make a $100 loan. The other $90 would be sourced from a bank’s deposits. A risk weight of 50 percent would mean that the same bank could make the same $100 loan using only $5 in equity capital (and $95 in deposits). The risk weight assigned to corporate loans is important because as banks are required to use more equity capital, the cost of lending rises because equity capital is the most expensive form of finance. Loans requiring more equity capital are more expensive and less available than loans requiring less equity capital.

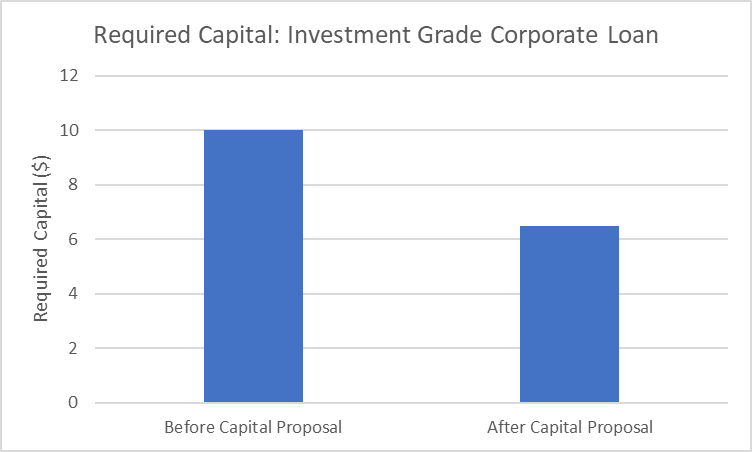

The Basel framework and the recent U.S. proposal both make a change to the risk weight for corporate loans. Specifically, corporations and businesses that have a demonstrated ability to repay their loans can be classified as “Investment Grade” and receive a reduced risk weight of 65 percent rather than 100 percent. In the context of our earlier example, this would mean that a bank could make a $100 loan using $6.50 in equity capital rather than $10.00. In the chart below, we show the difference in required capital for an Investment Grade corporate loan both before and after the proposed change to the capital regime.

In principle, this is a sensible and important change to the capital rules. All companies should not be painted with same brush. Financially responsible companies with a demonstrated ability to repay their debts are less risky and should require less equity capital. This clear link between “risk and return” is a bedrock principle of modern finance that should be reflected in bank capital requirements.

Smart Policy is Poorly Executed in the Capital Proposal

So far so good. Strong companies that are low risk can receive a lower risk weight of 65 percent and access bank financing on better terms, which makes a lot of sense. Where is the problem?

The problem arises from a provision of both the Basel and U.S. proposals that severely limits the application of Investment Grade status to only the largest public companies. Specifically, the only companies that are eligible to be classified as investment grade are companies that have “publicly traded securities outstanding,” such as debt or equity securities (see page 89 of 1087 in the proposal).

This limitation is not motivated by any sensible risk considerations and is completely unnecessary for two reasons.

First, there is no connection whatsoever between whether a company is high risk or low risk and whether it issues publicly traded securities. Publicly listed companies run the gamut from very conservative and low risk to the most speculative and risky of companies. A public listing is in no way a conclusive statement about underlying risk. And only the largest companies have the scale to issue public securities. At the same time, our economy is chock full of smaller companies that have borrowed and repaid many bank loans over an extended period. Why should these smaller companies with an established strong credit record be excluded from the Investment Grade designation?

Second, smaller companies that do not have the scale to issue publicly traded securities are precisely the companies that rely most heavily on bank borrowing. And most companies in the United States are indeed small. According to the Census Bureau, the U.S. economy has over 28 million companies and only about 4,200 – or .015 percent – of these companies are publicly listed. As a result, denying smaller creditworthy companies access to better funding excludes the vast majority of U.S. companies and these firms don’t have as many alternative funding sources as do the very largest companies that are publicly listed.

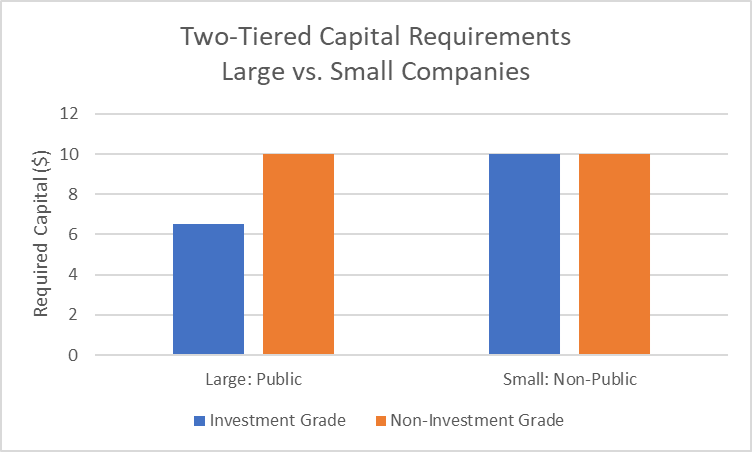

This unnecessary limitation will have the effect of creating a “two-tiered” credit system in which loans to creditworthy, public companies will require less capital than creditworthy small businesses as depicted in the chart below. As a result, bank lending to small businesses will be disadvantaged relative to lending to larger public corporations because smaller companies will be excluded from the investment grade classification.

Fixing The Mistake: Look Across the Pond

Both the UK and the EU are also in the process of implementing the 2017 Basel reform. Both the UK and EU proposals are cognizant of the potential for this type of limitation to severely harm small businesses and have taken steps to ensure that small businesses are not denied Investment Grade status simply because of their smaller size. U.S. regulators should closely consider the proposals made by the EU and UK and find a way to ensure that creditworthy, small businesses in the U.S. have access to needed bank funding at reasonable cost. In addition to the disadvantage relative to U.S. public companies, small and mid-market companies in the U.S. will be disadvantaged relative to UK and EU companies, which means they could lose out on valuable business overseas. Our capital rules should not unnecessarily make it harder for U.S. companies to sell and grow through trade.

Conclusion

Small businesses are important to the vitality and dynamism of the U.S. economy. One key aspect of newly proposed bank capital rules would unnecessarily and unfairly increase the cost and decrease the availability of lending to small businesses. This result is not based on any sensible measure of risk and is not appropriate. European and UK regulators have recognized that this outcome is not sensible and have adjusted their implementation of the Basel capital framework to ensure creditworthy, smaller companies are not cut off from accessing bank financing at reasonable cost. The U.S. agencies should adjust their proposal to ensure that new bank capital rules do not unfairly and inappropriately disadvantage small businesses from accessing bank credit.