Introduction

The size and depth of U.S. capital markets is the envy of the world and facilitates a significant amount of corporate investment that helps grow our economy. Companies raise funds from capital markets by issuing equity and debt securities to a variety of investors, including pension funds, mutual funds, and households. This critical activity is facilitated largely by large bank intermediaries that “make markets” in these securities. In the U.S., Financial Services Forum members account for roughly three-fourths of this market-making activity. U.S. regulators recently proposed a significant increase in bank capital requirements, known as Basel III Finalization, that would substantially increase the cost of market making. The proposal would increase the cost of corporate investment and for investors to buy and sell these securities in the open market. In this post, we will discuss the role of capital in market making, recent trends in market-making activity, the potential impact of the proposed requirements on the provision of market-making services by banks as well as their likely impact on overall financial stability.

Large Banks, Securities Underwriting, and Market Making

A wide range of U.S. companies raise investment funds from the public by issuing debt and equity securities. These funds are then used for a variety of investment purposes such as new factories, research and development, or expansion into new markets. All of these activities support our economy. Companies typically raise investment funds by partnering with a large bank to execute the sale of the securities. A large bank will buy a fixed amount of securities from the company and then market the securities to investors such as pension funds, mutual funds, and households who want to purchase these securities for saving and investment purposes.

Once the securities have been sold to investors, large bank intermediaries play a further, critical role. At some point, an initial investor, such as a pension fund, will need to sell the security it owns to raise cash. Similarly, another investor may have a need to purchase a security, perhaps because it has recently received cash that it needs to invest. Large bank intermediaries operate a constant market for these corporate securities to ensure that both buyers and sellers of securities have a ready market in which they can transact easily and at reasonable cost. Without banks acting as market makers, it would be very difficult and costly for buyers and sellers of corporate securities to adjust their holdings as their needs change. Accordingly, market-making activities by banks are critical to ensure well-functioning capital markets.

In order to maintain a ready market, large bank market makers maintain an inventory of corporate securities. This inventory is actively used to make markets and ensure that market participants can readily transact at reasonable cost. To analogize, this is akin to the inventory at a car dealership. A car dealer without any inventory will be hard-pressed to facilitate any car sales or purchases! Similarly, bank market makers need to maintain sufficient securities inventory to facilitate security purchases and sales. A market in which buyers and sellers can transact easily and at reasonable cost is known as a “liquid” market and market makers effectively provide liquidity to the public by maintaining a sizeable inventory of securities.

Bank Capital and Market Making

As we all know from watching the stock market, security prices go up and security prices go down. Accordingly, banks that actively hold sizeable securities inventories need appropriate capital to ensure that they can withstand market fluctuations. At the same time, equity capital is costly. As a result, while maintaining more capital improves a bank’s safety, it also raises the cost of providing market-making services to investors. Significant increases in required capital for market-making activity would increase costs and lead to smaller inventories and less liquid markets. Indeed, the past decade provides a clear case study of how increased capital requirements lead to less liquid capital markets.

Market Risk Capital Requirements and Market Liquidity: Recent Evidence

Following the 2008 financial crisis, bank regulators substantially raised the amount of capital that is required of banks to engage in market-making activities. These increased capital requirements came in two forms.

- First, global bank regulators increased market-making capital requirements through what is commonly referred to as “Basel 2.5.” According to regulators, Basel 2.5 increased market-making capital requirements by 40 percent.

- Second, in the U.S., bank regulators introduced a new stress testing capital regime that applied an extremely conservative “market shock” to market-making inventories that further increased required capital for market-making activities.

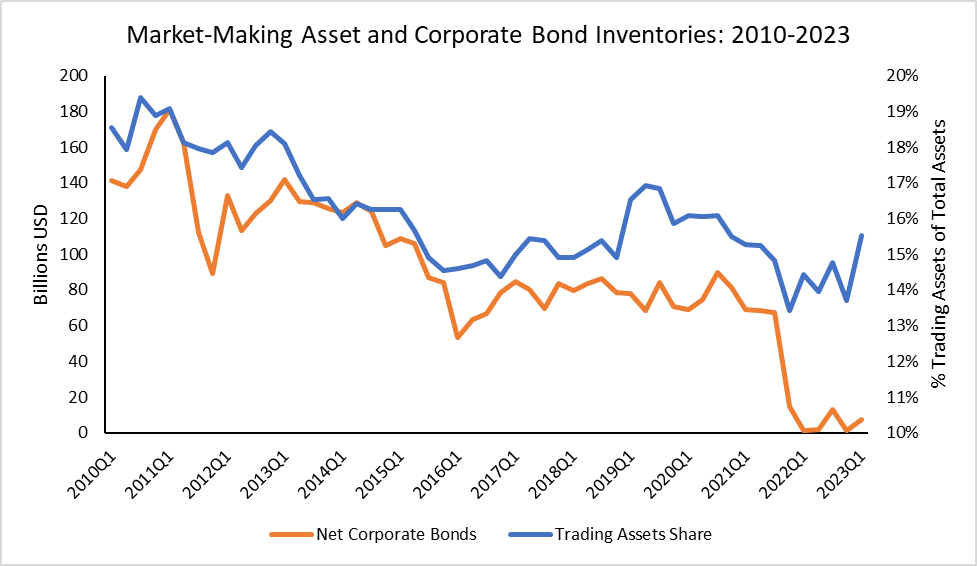

So, what has been the impact of these significant increases in capital requirements? The chart below addresses this question in two ways. First, the chart shows the proportion of all large bank assets devoted to market making assets such as stocks, bonds, commodities, and derivatives. Second, the chart also shows data for a narrower class of securities – corporate bonds held by market makers.

The fraction of market-making assets held by banks (blue line) has declined from roughly 20 percent to about 15 percent since 2010. The second line in the chart shows the experience for the more narrow class of corporate bonds (orange line). As shown in the chart, market makers have substantially reduced their inventory of corporate bonds over the same period. As regulators markedly increased required capital, large banks have reduced their inventories to conserve capital.

Source: Financial Accounts of the United States, Quarterly Trends for Consolidated U.S. Banking Organizations

Given the demonstrable decline in inventories, is there any evidence that capital markets have suffered as a result? Yes. A broad range of market commentary has noted a steady decline in the liquidity of capital markets over the past decade. In addition, reports from the official sector such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS) have discussed the issue of declining liquidity over the past decade, including the contribution arising from reduced inventories of market makers. The clear link between rising market-making capital requirements, declining inventories, and reduced market liquidity raises serious questions about a further, unnecessary increase in market-making capital requirements.

Proposed Bank Capital Increase is Unnecessary and Would Further Worsen Market Liquidity

The new requirements that are being proposed by U.S. regulators would significantly increase capital requirements for market-making activities. According to the proposal’s own analysis, the amount of large bank capital required to make markets would increase by more than 75 percent.

In light of such a significant increase in capital, it is important to ask what specific events or facts suggest such an increase is necessary? Previously we discussed Basel 2.5 and the advent of stress testing. Both developments followed the financial crisis. And while one may argue about the causes of the financial crisis or the role played by financial market activities, there was a clear economic event that precipitated these changes.

There is no analogous event or fact pattern in the present situation. U.S. regulators are proposing a substantial increase in the required capital for market making yet there have not been any events to suggest that these activities are undercapitalized. Rather, the contrary is true. During the real-world stress test of the COVID pandemic, financial markets came under significant stress, but large banks performed extremely well while also engaging in record-breaking amounts of securities underwriting to support a wide range of companies that needed financing to deal with the challenges presented by the pandemic.

An increase in required capital of this magnitude would only exacerbate recent trends that have challenged market liquidity. Ultimately, increased requirements would increase costs for companies seeking to make investments to grow the economy as well as savers looking for a liquid store of value for their hard-earned investment capital. At the same time, given the already significant increases in capital over the past decade, further increasing capital would have relatively small effects on the safety of market-making activities.

Increased Market-Making Capital Requirements Would Drive Activity Outside the Banking System

Finally, it is critical to consider the effect that raising capital would have on the overall composition of our financial system. Over the past decade or so, much capital market activity has migrated out of the highly regulated banking system and into less well-regulated non-banks. As a specific example, today roughly 50 percent of U.S. equity trading is handled by high-frequency trading (HFT) firms, which are outside the banking system. As bank capital requirements for market-making services increase, banks become less competitive in offering these services and non-banks may fill the void. A trend toward non-banks raises serious questions about financial stability as these non-banks typically are not subject to bank-style capital (or liquidity) requirements and may pose broader risks to financial stability – especially in times of market stress when market-making services are in such high demand. In this vein, analyses of events surrounding the COVID pandemic have suggested that non-banks were more fragile and less resilient than highly regulated banks. As a result, the current proposal to increase market-making capital requirements is even more concerning because it may further alter the balance of banks and non-banks in the provision of capital market services.

Conclusion

U.S. capital markets are the envy of the world. Everyday companies use these markets to raise funding for needed investments that grow our economy. At the same time, savers use these markets to find a liquid and valuable store of value for their hard-earned savings. Over the past decade or so, bank capital requirements have increased tremendously, and market liquidity has broadly declined, which has raised costs for companies seeking investment capital and savers looking for a solid financial return on their capital. The Basel III Finalization proposal would dramatically increase required capital for market-making activities by an additional 75 percent for large banks. The proposed increase is not tied to any observable increase in financial risks or specific events that would, in any way, suggest that market-making capital is too low. Rather, available evidence clearly demonstrates that large bank market makers have been resilient during times of stress while their non-bank counterparts have been demonstrably less resilient. Imposing unnecessary costs on companies, savers, and investors would harm our capital markets and the economy. U.S. regulators should revisit their proposal and avoid these impacts before finalizing, otherwise we will see further strain on market liquidity and increased potential for financial instability.