Introduction

This Spring, Federal Reserve Vice Chair for Supervision Michael Barr gave a speech previewing some changes to large bank liquidity regulations that may be proposed by the banking agencies. In particular, the Vice Chair indicated that the “regulatory adjustments we are considering would ensure all large banks maintain better liquidity risk management practices going forward.” The largest banks, however, already maintain heightened liquidity risk management practices. In this post, we review the current requirements for Forum members (U.S. GSIBs), discuss the lack of any nexus between the regional bank turmoil of last Spring and the state of Forum members, and make some recommendations to ensure that any proposed liquidity regulations are appropriately targeted, thoughtful, and, critically, informed by data and analysis.

SVB as a Pretext for Tighter U.S. GSIB Liquidity Regulation: A Shoe That Does Not Fit

The events of Spring 2023 that resulted in the failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank and stirred turmoil among a variety of U.S. regional banking organizations have been cited on several occasions as evidence that all large banks need tighter regulations for liquidity, or the assets banks have available to quickly meet short-term obligations. Unfortunately, this assertion misapplies the lessons from last Spring and does not recognize the liquidity profile and regulatory framework for U.S. Global Systemically Important Banks, or GSIBs.

The failure of SVB, Signature Bank and the turmoil that roiled some regional banks in 2023 had absolutely nothing to do with U.S. GSIBs. SVB and Signature were smaller regional banks that were not subject to the broad and extensive panoply of liquidity regulations that apply to U.S. GSIBs. More specifically, these regional banks, and other banks with similar size and activity profiles, were not and are not subject to:

- The most stringent form of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR)

- Resolution-based liquidity requirements (RLAP, RLEN)

- A supervisory liquidity oversight program through the Federal Reserve’s Large Institution Supervision Coordinating Committee (LISCC) – only U.S. GSIBs are covered by the Federal Reserve’s LISCC supervisory program.

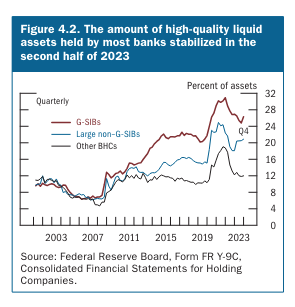

These requirements represent much more than an inscrutable regulatory alphabet soup. The extreme focus on U.S. GSIB liquidity since the financial crisis has had a transformative effect on the liquidity profile of U.S. GSIBs. To wit: consider the following chart and commentary from the Federal Reserve’s most recent Financial Stability Report.

In particular, the Federal Reserve said regarding High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA), “U.S. GSIBs continued to hold more HQLA (liquid assets) than required by the LCR – the requirement that ensures banks hold sufficient HQLA to fund estimated cash outflows for 30 days during a hypothetical stress event.” As the chart, and the statement in the Financial Stability Report clearly show, U.S. GSIBs maintain ample liquidity that is well ahead of other U.S. banks. In the face of such clear and unambiguous data, it is difficult to fathom why regulators would think that U.S. GSIBs require even stricter liquidity requirements.

Finally, two specific events that unfolded during last year’s regional banking turmoil clearly demonstrate the liquidity strength of Forum members. First, as documented in research conducted by the Federal Reserve, Forum members actually gained deposits during this period as households and businesses sought the safety and stability provided by Forum members with their high levels of capital, liquidity and overall resilience. Second, amid the unfolding turmoil, Forum members were called upon to help stabilize another struggling bank, First Republic, and contributed the majority of a $30 billion liquidity injection to First Republic to provide regulators more time to resolve the failing bank.

The strong liquidity profile of Forum members as well as the actual events of Spring 2023 clearly indicate that U.S. GSIBs do not have any liquidity problems requiring redress. Rather, Forum members are a source of liquidity strength and resilience that supported the banking sector and the entire economy during that challenging period. Accordingly, any suggestion that the events of SVB “clearly show” a need for more and tighter liquidity regulation for Forum members is plainly inconsistent with the clear and incontrovertible facts from that event.

A Way Forward on Liquidity Regulation

Vice Chair Barr’s speech clearly indicates that regulators are preparing to suggest some important changes to bank liquidity regulation. The issues that regulators are considering are quite complex and would impact the entire economy. Accordingly, regulators should be committed to getting it right rather than getting it done.

A precondition to getting it right is clearly defining the problem to be solved with due regard for differences in the state of liquidity profiles and liquidity regulation across the banking sector. Accordingly, before any new liquidity regulations are proposed, banking regulators should release a data-based, comprehensive analysis of the existing liquidity regulatory framework that clearly identifies the specific problem that needs to be addressed. Importantly, the report should clearly account for the graduated stringency of regulation that is applied to larger and larger banks with Forum members being subject to the most stringent liquidity requirements. The analysis and data used to arrive at its conclusions should be available for public comment.

Recently, the banking sector has dealt with a capital proposal that was subsequently followed by a data collection that is being used to further define and refine the policy proposal. This approach has raised several legitimate and difficult to cure process concerns that should be avoided in the context of any future liquidity proposals. These process concerns can be squarely addressed by taking a systematic, thoughtful, and data-based approach to liquidity regulation that clearly communicates the specific problem at hand before any proposals are issued.

Following the release of the analysis and a review of the comments, regulators may come to the view that changes to the liquidity regime are warranted. If that is the case, banking regulators should begin by first issuing an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR). An ANPR is often used by regulators to thoughtfully engage with the public and seek information prior to issuing a specific proposal. The use of an ANPR gives regulators the opportunity to gather data and information that can be helpful in calibrating a regulatory proposal. Such public engagement is a hallmark of a deliberate and thoughtful regulatory process that puts “Getting it Right” ahead of “Getting it Done.”

The Federal Reserve Should Put Discount Window Reform Ahead of Any New Regulation

Finally, it is important to consider other important lessons from the recent regional bank turmoil. One clear lesson from the 2023 turmoil is that the Federal Reserve’s discount window is in serious need of reform. The events surrounding SVB revealed that the Federal Reserve’s discount window operations – which allow financial institutions to borrow from the Federal Reserve – have not kept pace with basic advancements in information technology that have transformed our whole economy in the past thirty years. An antiquated and largely manual discount window cannot possibly serve a modern banking system that is defined by sophisticated and highly automated information technologies. The deficiencies of the discount window are so glaring that Congress has offered legislation to “reform the Federal Reserve’s discount window for the 21st century economy.” Launching a raft of new liquidity regulations before addressing longstanding and significant problems with the discount window would be a clear case of putting the cart before the horse. The discount window is an integral component of the bank liquidity landscape, so ensuring that it operates efficiently and effectively should be a precondition to any new regulation. A modernized and well-functioning discount window will itself improve bank liquidity throughout the entire banking sector and complement existing bank liquidity regulation.

Conclusion

Increasingly regulators are asserting that the large bank liquidity framework needs repair. The assertion is largely based on the idiosyncratic failure of a few smaller institutions last Spring that bear no resemblance in any way, shape, or form to Forum members. The use of that historical episode as a pretext for more stringent GSIB liquidity regulation is wholly inconsistent with the unambiguous facts concerning the liquidity profile of U.S. GSIBs and that unfortunate event. If regulators are determined to launch an effort to change the existing liquidity regime, they should begin by providing the public with a data-based and comprehensive analysis that clearly identifies the specific shortcomings that need to be addressed. Any subsequent proposals should be preceded by an ANPR to facilitate a deliberate and thoughtful approach to regulation that will prove to be appropriately calibrated and durable. Finally, regulators would do well to turn their attention to addressing clear deficiencies with the discount window before launching a raft of new and unproven liquidity regulations.