Introduction

Since the 2008 Financial Crisis, the implementation of the Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIB) framework has become a crucial aspect of financial regulation. GSIB banks, which comprise all Forum members as well as a significant number of large, foreign banks, are subject to an additional capital requirement known as the “GSIB Surcharge.” The GSIB surcharge depends on a large number of technical, data-dependent indicators that form the basis of a “GSIB Score” that then is translated into a GSIB Surcharge. Since the GSIB framework was introduced, GSIB scores have been measured at a quarterly frequency with GSIB surcharges depending on measured GSIB scores at the end of the fourth quarter.

Recently, both the Federal Reserve and global regulators through the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) have proposed increasing the measurement frequency of these technical indicators. Under the proposals, GSIBs would be required to measure these indicators at a daily, rather than quarterly, frequency.

Why this change to longstanding and accepted practice? Regulators have argued that GSIBs engage in “window dressing” to influence the level of their capital surcharges. More specifically, regulators argue that GSIBs manipulate the level of these indicators at the end of the fourth quarter to achieve temporarily lower scores and surcharges. The BCBS recently issued a staff working paper making this claim. Relatedly, prior research from the Federal Reserve Board conducted a related analysis claiming that U.S. GSIBs have engaged in “window dressing.” As a result, regulators have taken the view that high frequency, i.e. daily, calculation of indicators and scores will counteract window dressing behavior by banks.

In this blog, we explore the evidence in favor of window dressing using U.S. data from 2018-2023 that is relevant to U.S. GSIBs (Forum members). The data do not present a clear, compelling, and incontrovertible case for systematic window dressing by U.S. GSIBs. We discuss these results in the context of related economic forces that may be influencing GSIBs and non-GSIBs alike.

GSIB Surcharge Mechanics, Data and Analysis Framework.

As discussed, the GSIB Surcharge is based on each GSIB’s “GSIB Score” as measured at the end of the fourth quarter. Importantly, the resulting GSIB Surcharge remains in force for at least one year. As a result, if a GSIB were able to lower its score temporarily at the end of the year it would benefit as the resulting lower surcharge would persist until, at least, the following year.

The Federal Reserve requires that both U.S. GSIBs and non-GSIBs track and publicly report the indicators that are needed to compute the GSIB score on a quarterly basis. As of the first quarter of 2024, 37 banks – the eight Forum members and 29 additional U.S. banks – are required to disclose these data. In principle, non-GSIBs are required to disclose these data in case one of them grows large enough to become a GSIB. Practically speaking, given the current GSIB framework, non-GSIBs are not anywhere close to qualifying as a GSIB. As a result, these banks have no incentive to manipulate or “window dress” their indicators and resulting GSIB scores because they are not subject to the GSIB Surcharge. Accordingly, non-GSIBs and their GSIB scores serve as a useful “control” to compare against the GSIB scores of GSIB banks. Importantly, behavior that is exhibited by both GSIBs and non-GSIBs alike can’t reasonably be attributed to “window dressing” as non-GSIBs have no window dressing incentives.

In the analysis that follows we compare the change in GSIB scores from the third to fourth quarter for every bank included in the GSIB score measurement sample from 2018-2023.

GSIB Score Behavior at the End of the Year: GSIBs and Non-GSIBs

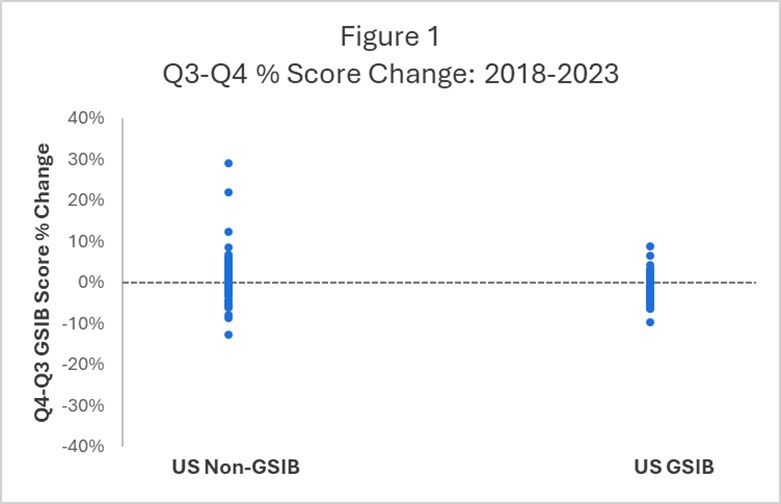

Below, we show the percentage change in GSIB scores between the end of the third quarter and the end of the fourth quarter for both GSIBs and non-GSIBs over the 2018-2023 period. Conceptually, the percentage change in score is a natural and relevant measure to assess whether window dressing is occurring because U.S. GSIBs are more complex and have correspondingly larger GSIB scores than their non-GSIB counterparts.

The results of this analysis are presented in Figure 1. In Figure 1 we provide a dashed line at a value of zero for reference and comparison. A value that is below zero indicates that the score is declining at the end of the year, consistent with the window dressing hypothesis, while a value that is above zero indicates a rising GSIB score at the end of the year, which would portend a rising surcharge contrary to the window dressing hypothesis.

Source: Federal Reserve Y-15

The first observation from the results presented in Figure 1 is that both GSIBs and non-GSIBs alike display a significant number of cases in which GSIB scores rise at the end of the year. If GSIB score management is a key consideration for GSIBs, it is hard to understand why we would see their scores rise at the end of the year as a rising score would only tend to increase the resulting surcharge.

Looking further at Figure 1 does show that there are also cases in which GSIB scores decline at the end of the year. At the same time, however, the data also show that non-GSIBs exhibit a number of cases in which GSIB scores also decline at the end of the year. To the extent that both GSIBs and non-GSIBs exhibit declining GSIB scores at the end of the year, it is difficult to attribute this behavior to “window dressing” as non-GSIBs have no window dressing incentives.

If window dressing were a clear and obvious driver of GSIB Scores for GSIBs at the end of the year, we would expect the data presented in Figure 1 to show a clear and obvious difference in the end-of-year behavior of GSIBs and non-GSIBs – a smoking gun if you will. The data presented in Figure 1 reveal quite the opposite. Both GSIBs and non-GSIBs alike exhibit variable GSIB scores at the end of the year that sometime increase, sometimes decrease, and sometimes stay the same. The data presented in Figure 1 do not present any clear and obvious differences between GSIB and non-GSIB behavior at the end of the year.

Jumping to Conclusions: Conflating Seasonal Effects with Window Dressing?

As discussed, regulators have taken the view that GSIBs actively engage in window dressing and that a regulatory response is required to counteract this behavior. The data presented above tell a much more nuanced story.

As presented above there is no incontrovertible evidence to support the window dressing hypothesis. If window dressing is not the motivation of year-end score movements, it begs the question “then what is?” The end of every year is typically characterized by various seasonal or “calendar” impacts. For example, firms of all kinds engage in extensive tax planning and take a variety of tax-related actions at the end of the year. End-of-year accounting management is also widely practiced across a variety of industries including banking. Finally, firms also typically renew and renegotiate customer and vendor relationships at the end of the year in a way that may have impacts on overall activity levels and end-of-year GSIB scores. Regulator statements that end-of-year GSIB scores are driven solely by window dressing fail to consider the fact that the adjustment to banks’ financial positions at year-end may be motivated by a number of legitimate purposes other than lowering GSIB surcharges.

This point is especially important as a conceptual matter. Simply because regulators observe GSIB scores declining at the end of the year at some banks does not mean that they can assume that all observed end-of-year GSIB score variation is the result of window dressing. More broadly, observing behavior consistent with a preconceived hypothesis does not “prove” that notion to be true when a variety of other reasons may explain the same observed behavior. Importantly, the previously described research conducted by the BCBS and Federal Reserve failed to consider other important sources of GSIB score variation beyond their previously maintained “window dressing” hypothesis.

Conclusion

Regulator concerns regarding window dressing of GSIB scores are not unequivocally supported by the data. Using regulatory data on both GSIBs and non-GSIBs reveal several similarities in the end-of-year behavior of GSIB scores across both GSIBs and non-GSIBs alike. The data do not present a “smoking gun” in favor of GSIB window dressing. Moreover, neither these data nor the data analyzed in other regulator analyses identify the specific intent underlying observed GSIB score changes and do not adequately address the potential impact of typical end-of-year calendar effects that are frequently observed across a range of industries. Regulator proposals to substantially increase the cost and burden of GSIB score reporting through daily reporting requirements should more carefully consider the various potential causes of observed GSIB score behavior.