Introduction

Recently, the Federal Reserve indicated that banking regulators will soon release a proposal to implement a further revision to the large bank capital framework, known as Basel III Finalization. This “final” round of Basel reforms is often described as putting the “finishing touches” on the Basel III capital regime. Unfortunately, there are bigger and more consequential open issues with the current large bank capital regime that should be addressed before any “finishing touches” are considered. Moving ahead with Basel III Finalization before addressing these more fundamental concerns would be akin to painting the exterior of a new house before the roof has been finished. A house with a beautiful exterior that floods whenever it rains may have lots of curb appeal and may please the neighbors, but isn’t very functional for its inhabitants. In this post, we discuss the state of the large bank regulatory regime and review some important and long-standing concerns that should be addressed before moving ahead with Basel III Finalization.

The Basel Process is Broken and Must Be Reformed

Basel III Finalization is part of a broader, international standard-setting process in which regulators around the globe negotiate capital standards for internationally active banks. The underlying rationale for global coordination of capital policy is that banking is a global business and even small differences in capital regulation can drive large and destabilizing changes in banking activity. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) has been setting global capital standards since 1988, but recent events strongly suggest a fundamental breakdown in the process that runs counter to the BCBS’s raison d’etre: globally coordinated and consistent bank capital requirements.

Specifically, the European Union (EU) has proposed implementing Basel III Finalization in a way that significantly deviates from some of its key provisions and would lower the amount of capital required for EU banks relative to the amount that will be required of other banks implementing the reforms. European members of the Basel Committee have warned that this departure will “risk undermining global cohesion.” But this is not the first instance in which the EU banking sector has played by its own rules. Leading examples include not implementing other aspects of the Basel III reforms as well as recent EU-led changes to the GSIB surcharge methodology specifically designed to benefit certain EU banks.

This breakdown in the Basel process is fundamentally concerning and should be addressed before any additional Basel reforms are implemented in the U.S. Continued implementation of Basel capital reforms that are implemented differently would likely mean that capital requirements for U.S. banks would be raised while other banks around the world would not face the same increases. That would result in increased competitive inequities that undermine, rather than strengthen, the global capital framework.

Large U.S. Banks Are Already Highly Capitalized

The Basel III Finalization package is expected to raise capital requirements for large U.S. banks. Indeed, the EU deviations described above are motivated by the desire of the EU to soften the blow of the oncoming increases in capital requirements for European banks. Before moving ahead with Basel III Finalization, policymakers should consider one basic question: Do U.S. banks need additional capital and if so, why?

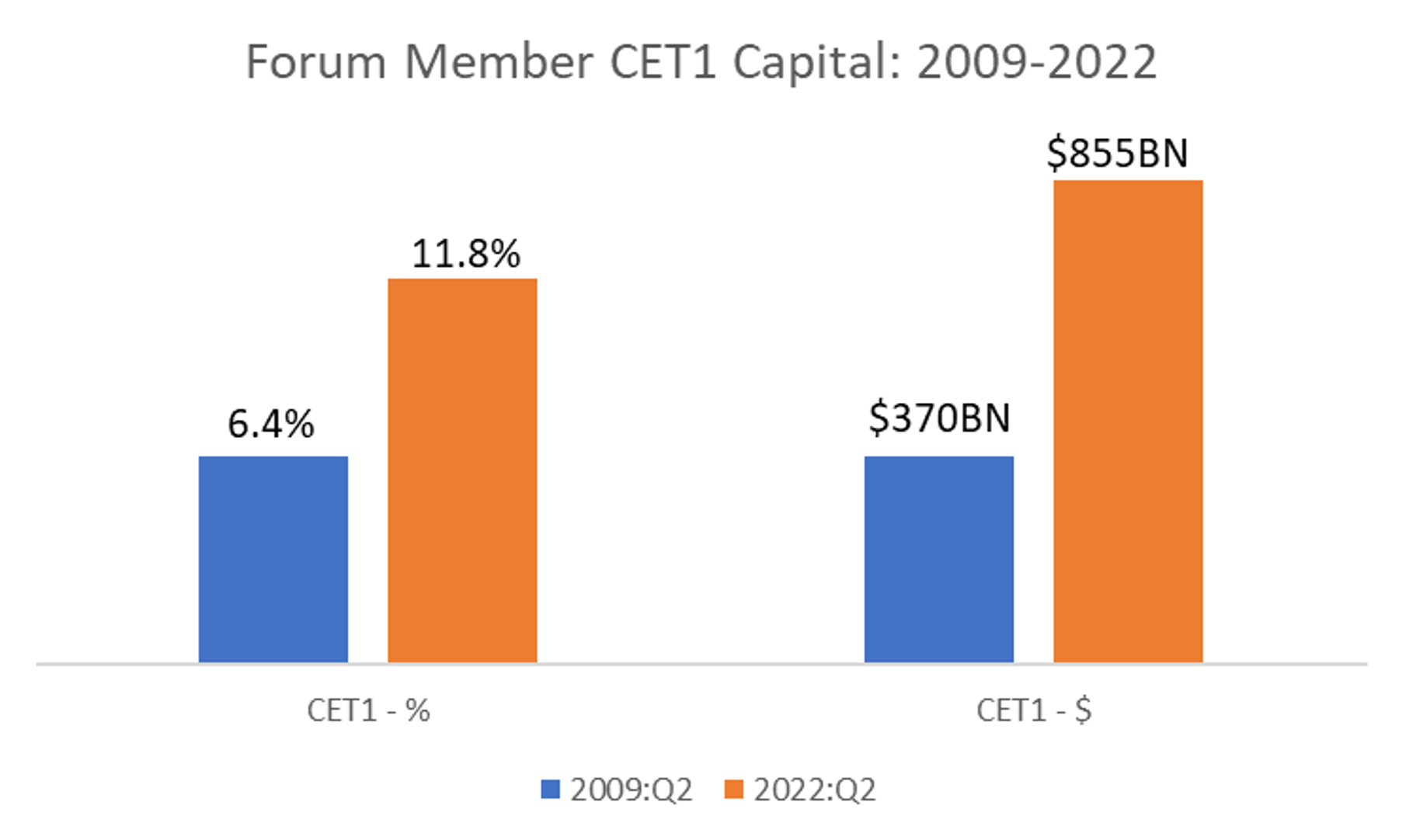

The data and experience with respect to large bank capital levels is clear. Large banks have substantially raised their capital levels – both in absolute dollar terms and in proportion to their risk-weighted assets – over the past 15 years as shown in the figure below. In addition, as noted of large banks in the Federal Reserve Board’s most recent Supervision and Regulation Report, “recent stress test results suggest that these firms remain sufficiently well capitalized to continue lending to households and businesses in a simulated period of stress.” Finally, the recent real world stress test of the pandemic clearly showed that banks are a source of strength to the economy. Simply put, there is no compelling evidence suggesting that large banks suffer from a dearth of capital.

Capital is not a free resource in the economy. Ever increasing amounts of required capital will continue to push up the cost of lending and reduce economic growth.

The Existing Large Bank Capital Regime Needs Significant Reform

The Federal Reserve has recently announced a holistic review of the large bank capital regime. This review affords bank regulators with an important opportunity to take a step back and assess the current state of large bank regulation. Any reasonable review of the framework will show that there are several aspects of the capital regime in need of structural reform. These structural reforms should be undertaken, completed, and assessed over a period of time before any “finishing touches” are applied. A short list of reform areas would include:

Review and recalibrate the GSIB Surcharge – Upon finalizing the GSIB surcharge in 2015, the Federal Reserve committed to periodic reviews of the GSIB surcharge to reflect economic growth. In addition, the pandemic has revealed significant deficiencies with the GSIB surcharge that also need to be addressed. The largest banks have safer balance sheets because of their increased reserve holdings caused by the Federal Reserve’s pandemic response, yet their GSIB capital charges – intended to reflect systemic risk – have increased merely due to the increased amount of those riskless assets. Any legitimate holistic review of the existing large bank capital regime must include a reconsideration and recalibration of the GSIB surcharge.

Review and recalibrate the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) – Over the past few years, and especially since the onset of the pandemic, the SLR has become increasingly binding and has meaningfully contributed to declining liquidity in the U.S. Treasury market. Treasury market functioning has deteriorated so much that the Group of 30 recently published an update to its 2021 report exhorting regulators to recalibrate the SLR. In addition, recent research from Federal Reserve economists finds that the SLR materially disincentivizes bank participation in the U.S. Treasury market. In light of the importance of the U.S. Treasury market to the U.S. economy and overall financial stability, it is imperative that regulators act quickly to address this significant problem.

Review and reform the stress testing and stress capital buffer (SCB) process – The stress testing process that results in the annual determination of SCBs is opaque and results in substantial year-to-year variation in SCB levels. Over the past three years, the stress testing process has resulted in SCBs that fall by more than half for some while others have nearly doubled from one year to the next. This variability in year-to-year capital requirements injects unnecessary and unhelpful volatility that frustrates good, long-term capital planning. In addition, the opaque nature of the stress tests often produces results that are hard to align with any sensible notion of risk. The stress testing process should be overhauled to improve public transparency and reduce volatility.

Conclusion

Large U.S. banks are well capitalized and are serving our economy well in this period of heightened uncertainty and economic headwinds. There is no compelling evidence to suggest that large U.S. banks are anything but robustly capitalized. Over time, a number of significant and structural shortcomings with the current large bank capital framework have become apparent. These problems have been demonstrated over time and are based on hard facts, data, and research. Regulators should commit to reviewing and addressing these shortcomings before putting further “international” reforms into effect. Finally, the process for international coordination of bank regulation should be overhauled to ensure full coordination and implementation by all parties. A fractured system of coordination in which some countries routinely raise capital standards while others do not will increase, rather than reduce, financial instability and risk.