Introduction

Over the past 1-1/2 years, large banks have seen a massive increase in their deposits and overall balance sheets as outstanding Federal Reserve balances at banks have more than doubled as a result of the pandemic and related government actions to support the economy. As a result of this balance sheet expansion, the risk-insensitive supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) capital requirement has become more binding and now requires more capital in the aggregate than risk-based capital requirements for Forum members. In this blog, we document the increasingly binding nature of leverage capital requirements, outline the problematic nature of a binding leverage requirement, and discuss the prospects for restoring risk-based rather than leverage capital as the binding capital constraint for large banks.

Leverage and Risk-Based Capital Requirements: Moving from the Backstop to the Frontstop

Financial Services Forum members are subject to both leverage capital and risk-based capital requirements. Forum members must maintain enough Tier 1 capital to yield an SLR of 5 percent. The SLR is a risk-insensitive capital requirement that effectively requires a bank to maintain the same amount of capital for every asset on its balance sheet whether it be cash, a U.S. Treasury bond, or a corporate loan. In addition, Forum members must also maintain a risk-based capital requirement of 6 percent of Tier 1 capital, plus a stress capital buffer that ranges from 2.5 percent to 6.4 percent, plus a GSIB surcharge buffer that varies between 1 percent and 3.5 percent. Risk-based capital requires a different amount of capital for each asset based on its risk profile. Accordingly, a U.S. Treasury bond requires less capital than a corporate loan. Ultimately, a bank must maintain enough capital to satisfy whichever requirement results in a greater dollar amount of capital.

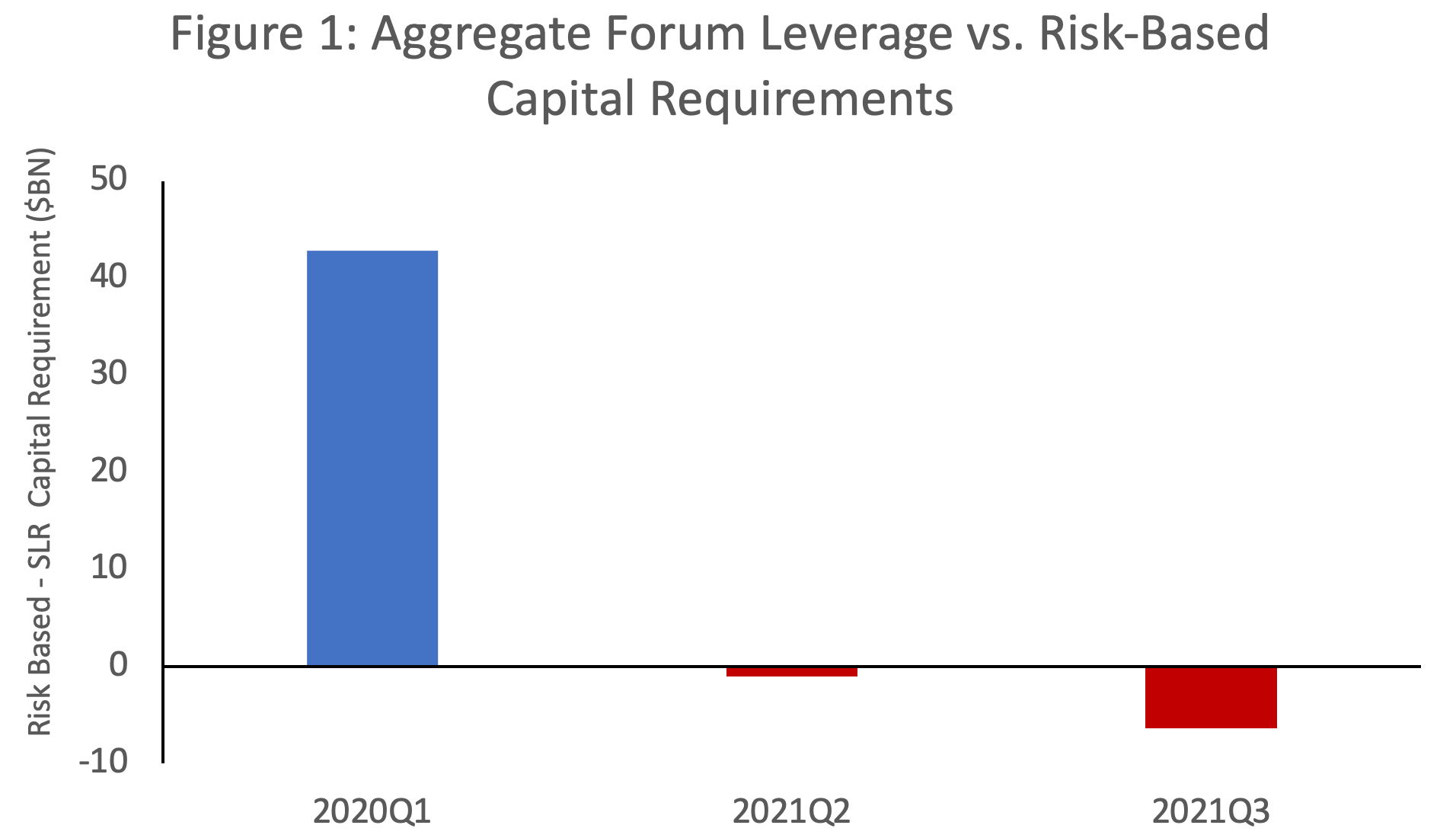

Figure 1 shows the difference between the aggregate amount of Tier 1 capital required by risk-based and leverage capital requirements from 2020Q1 through 2021Q3 for Forum members. We omit quarters over which the Federal Reserve excluded reserves and U.S. Treasuries from the SLR so that the amounts can be meaningfully compared. As can be seen in Figure 1, in the first quarter of 2020 (the very beginning of the pandemic), the amount of Tier 1 capital required by risk-based capital requirements was roughly $40 billion more than the amount required by the SLR (the blue bar in Figure 1 is positive $40 billion). As a result, risk-based capital was the binding capital constraint, which means that decisions to allocate funding to lending and other activities would be made based on their risk profile, which incentivizes sound risk management and supports overall safety and soundness.

More recent data, however, clearly show that the risk-insensitive SLR is requiring more capital in the aggregate than risk-based requirements. Specifically, the red bars in Figure 1 from the most recent two quarters are negative, which shows that the SLR is requiring more capital than the risk-based requirement. And the most recent data from the third quarter of 2021 show an increase in the amount of capital required by the SLR relative to risk-based requirements (as the bar associated with Q3 2021 in Figure 1 is more negative). The increase in SLR capital is driven by the continued increase in bank balance sheets as the Federal Reserve has continued its accommodative monetary policy, such as asset purchases, leading to an expansion in bank balance sheets and increased leverage requirements relative to risk-based counterparts.

The Importance of Keeping Leverage Requirements in the Background

Regulators have long recognized that risk-insensitive leverage requirements should serve as a backstop to risk-based requirements and that risk-based requirements should serve as the binding capital requirement. As previously stated by the chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell: “A risk-insensitive leverage ratio can be a useful backstop to risk-based capital requirements. But such a ratio can have perverse incentives if it is the binding capital requirement because it treats relatively safe activities, such as central clearing, as equivalent to the most risky activities.” Accordingly, as the SLR becomes more binding, large bank incentives become more distorted and bank funding decisions become increasingly disconnected from risk and soundness considerations.

The view that leverage requirements should not be the binding capital constraint is founded on well-established economic thinking and research. Specifically, economists such as Stanford’s Darrell Duffie have shown how binding leverage requirements reduce incentives to engage in low-risk activities, such as intermediating U.S. Treasury markets. Further, Harvard’s Jeremy Stein, a former governor of the Federal Reserve, has pointed out how binding leverage requirements reduce heterogeneity among banks, which creates greater concentration and reduces diversification in the banking industry. As a result, the increasingly binding nature of leverage capital requirements documented in Figure 1 is a cause for concern because of the perverse effects of a binding leverage constraint.

Restoring Leverage to the Background: The Path Ahead

At the beginning of the pandemic, the Federal Reserve acted quickly to exclude holdings of cash and U.S. Treasuries from the SLR calculation. This act was fully appropriate because neither cash nor U.S. Treasuries contribute any significant risk to a bank’s balance sheet. Both cash and Treasuries are low-risk assets that provide banks with an important source of liquidity. In March 2021, the Federal Reserve ended these exclusions, but also indicated that they would “soon be inviting public comment on several potential SLR modifications.”

The data presented in Figure 1 clearly demonstrate that the time has come to modify the SLR. Importantly, holdings of low-risk assets that do not meaningfully contribute to risk should not require significant amounts of capital. The simple and transparent approach of excluding these holdings from the SLR calculation, as previously adopted by the Federal Reserve, achieves this result and would go a long way toward ensuring that leverage requirements act as a backstop and not the binding capital constraint.

Some have argued that any change to the SLR must be “capital neutral,” which generally means that the total amount of capital required from large banks should not decrease. Such an approach is problematic precisely because the SLR has become too binding and has leaped in front of risk-based requirements. A change to the SLR that removes cash and Treasury exposures and then “adds back” some arbitrary amount simply reestablishes the problem that needs to be solved: leverage capital requirements are too binding. Other complicated schemes that have been floated, such as excluding some but not all cash and Treasury holdings, suffer from the same problem while increasing the complexity of the capital framework. Ultimately, the appropriate amount of capital for large banks should be fully determined by risk-based requirements. Currently, bank regulators are considering a significant recalibration of risk-based requirements through the Basel III Finalization process. Rather than focusing on leverage requirements, regulators should simply and quickly restore leverage requirements to the background and move on to updating risk-based requirements. Such an approach would restore appropriate incentives while ensuring the primacy and relevance of risk-based requirements.

Conclusion

Regulators have long recognized that leverage requirements should serve as a backstop and not the binding capital requirement for large banks. The events of the pandemic have created a situation in which leverage requirements are having an outsized influence on large bank capital requirements. Binding leverage capital requirements result in distorted incentives that are highly problematic for the efficient allocation of resources in the economy. The Federal Reserve should modify the SLR to ensure that it remains in the background and does not serve as the binding capital constraint. Regulators can also ensure the appropriateness of risk-based requirements by moving ahead to update them through the Basel III Finalization process. Doing so would place appropriate emphasis on risk-based, rather than risk-insensitive, capital requirements.