Some members of Congress recently introduced a bill that would levy a tax on the purchase of stocks, bonds and other financial instruments. Such a tax, known as a financial transaction tax, or “FTT,” is not new as it has been tried in the past in the U.S. and abroad. As a result, we have considerable experience with FTTs that can be used to assess their potential impact.

Both economic reasoning and historical evidence suggest that an FTT would reduce household savings and overall well-being, increase financial risks, raise the cost of trading and reduce investment. FTTs also incentivize tax avoidance behavior that would reduce any amount of revenue raised by the tax. Overall, the wide-ranging and substantial costs of FTTs clearly outweigh the benefits of any additional tax revenue they may raise.

Before delving into the arguments and data that support this view, it is worthwhile to briefly review some FTT history. In 2011, the European Union proposed an FTT covering the entire European Union, but the proposal has floundered as EU countries have been unable to agree to a common set of tax terms. In the United States, an FTT was levied at the federal level between 1914 and 1965. New York state imposed its own FTT between 1932 and 1981. In both of these cases, the taxes were abandoned as experience demonstrated that they had a number of unintended and unhelpful effects on households, markets and the economy. Moreover, while some FTTs exist today, such as in the U.K., these taxes create a number of distortions and result in avoidance schemes that impair their effectiveness.

FTTs Are Not About “Unnecessary Speculation”

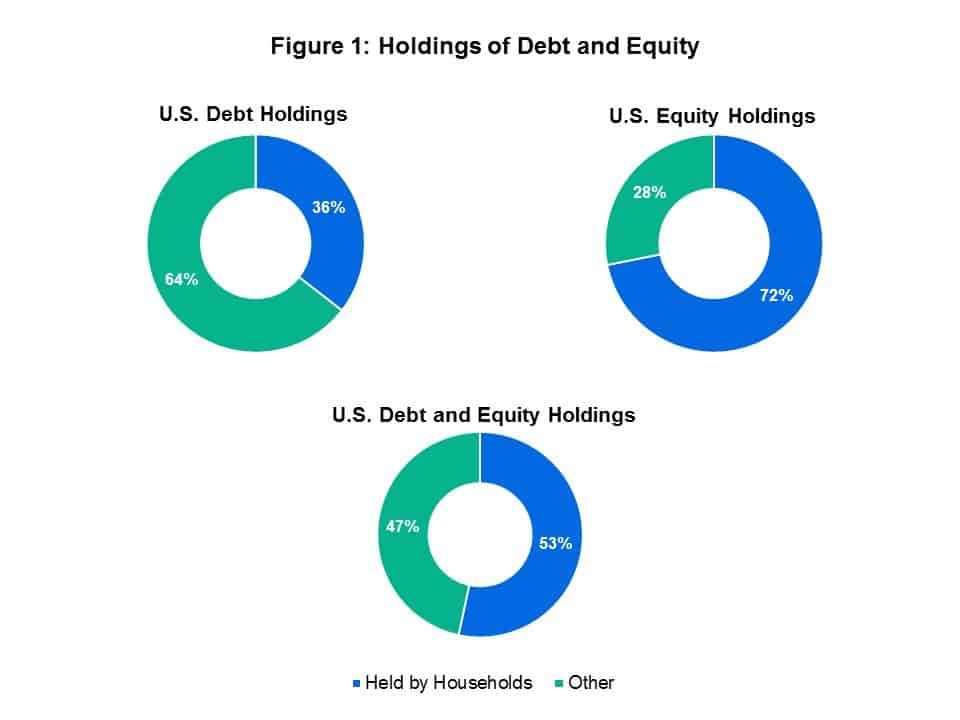

FTTs are often described as taxes that are designed to discourage outright “speculation” and discourage “unnecessary trading.” In reality, however, it is impossible to identify “speculation” or “unnecessary trading” and so the tax falls upon everyone who buys and sells financial assets. As shown in Figure 1, U.S. households own (directly or indirectly) over 50% of the equities and bonds that would be subject to an FTT. Accordingly, households that engage in financial transactions on a regular basis to save for the future and build financial security, would directly bear the costs of an FTT. And this is true regardless of whether the household purchases assets directly or indirectly, including through the ownership of mutual funds or a stake in a pension plan. More broadly, the idea that an FTT only impacts finance professionals such as hedge fund managers or high frequency traders is incorrect. Anyone who trades financial assets will bear the cost of the tax.

Sources: Federal Reserve data, Financial Accounts of the United States – Z.1, available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/Z1/current/default.htm, Staff Calculations

Note: Held by Households calculated as households and non-profits and pension (private, federal, state, and local) direct holdings as well as indirect holdings in mutual funds, money market funds, and exchange-traded funds.

One of the most reliable findings from economic research examining the impact of FTTs is that their imposition reduces trading activity. This finding has been observed in various contexts and supports one of the few universally accepted maxims in economics – if you tax something, then you get less of it. According to a 2016 review article in the National Tax Journal authored by researchers at the Brookings Institution, “empirical evidence strongly confirms that higher transaction costs in general, and a higher FTT in particular, reduce trading volume.”

While these reductions in trading volume are often characterized as reducing an “unnecessary” activity, it is important to understand that households and businesses have legitimate reasons to trade and that reduced trading activity imposes a cost that should not be overlooked. Consider, for example, a household that is shifting into retirement and wants to convert a portion of its riskier equity holdings to more stable, income-producing bonds. While this type of portfolio rebalancing represents common financial advice and prudent risk management, an FTT would raise the cost of this transaction. Households facing the tax may decide to rebalance less of their portfolios, which would result in increased risk and reduced financial security. Accordingly, reductions in trading activity that result from the tax are likely to have negative consequences for households that have a variety of legitimate motives to trade financial assets. As a result, the idea that FTTs do not impose a cost since they only discourage “excessive” or “unnecessary” trading is incorrect.

FTTs Increase Volatility and Risk Rather than Reduce Risk

FTTs also increase volatility and subject households to more financial risk. Economic reasoning holds that FTTs increase volatility because movements in asset prices that are not warranted by fundamentals are less likely to be acted upon by investors who want to “take the other side” since the tax discourages trading. This process is generally referred to as “price discovery” by economists. Robust price discovery in which market participants incorporate information into market prices to limit large price swings is a hallmark of an efficient financial system. The 2016 review of FTTs by the National Tax Journal documents that six out of seven studies found that FTTs raise volatility and risk Moreover, this finding is important because some proponents of FTTs claim that they reduce volatility by discouraging “unnecessary trading.” This claim is simply at odds with most of the empirical studies that have examined the impact of FTTs on risk and volatility.

FTTs Reduce Liquidity and Increase Costs

FTTs also raise the cost of trading separate and apart from the direct impact of the tax. One component of the cost of trading a stock or bond is the bid-ask spread, which is akin to the difference between wholesale and retail prices. Firms that make markets in financial assets for their clients earn a profit by buying assets at a lower price than at which they sell them. This is directly comparable to a grocery store that earns a profit by buying coffee at a lower wholesale price and then selling it to customers at an increased retail price. Because FTTs reduce trading and raise risk, making markets becomes riskier. In order to be compensated for the increased risk, market makers charge a higher bid-ask spread. A recent study of the New York state FTT by economists at Rutgers University and the Central Bank of Canada found that increases in the New York state FTT led to a direct and significant increase in bid-ask spreads and overall transaction costs.

FTTs Reduce Investment and Economic Growth

Apart from reducing household savings, increasing financial risk and increasing the cost of trading, FTTs also reduce investment and growth. The tax on trading imposed by an FTT generally reduces the benefit of owning a financial asset. As a result, owners of financial assets are willing to pay less for the asset being issued by the firm, which then results in lower proceeds to fund investment. According to a research paper by John Campbell and Kenneth Froot of Harvard University, “[t]he imposition of an [FTT] reduces shareholder wealth and increases the cost of capital to firms. This means that one would expect an [FTT] to decrease investment within a country and hence to have a negative impact on growth.”

The U.S. economy is home to a vibrant and efficient capital market that enables households to build financial security while funding investment to create economic growth. An FTT would discourage capital market participation when we should be promoting policies that encourage more households to build wealth and financial security through capital market participation. Both historical experience and economic research show that FTTs impose significant costs on households, markets and businesses. Whether it be increased costs, increased risk, or reduced investment and growth, the costs imposed by an FTT outweigh the benefits of any revenue raised by the tax.