Large U.S. banks are subject to stricter capital requirements and maintain more equity capital on their balance sheet than their European competitors. Over time, internationally agreed-upon capital rules have been implemented more stringently in the United States than in Europe. As a result, and quite perversely, international efforts to create a level playing field have resulted in an unlevel one.

Regulators around the globe are now engaged in implementing another round of internationally agreed-upon capital reforms, known as Basel 3 Finalization. And once again, there are clear signs that U.S. regulators will implement these reforms more stringently than other regulators, further widening the capital disparity between large U.S. and European banks. In this post, we document the existing capital disparity between large U.S. and European banks and then discuss the implications for further regulatory tightening by U.S. regulators. Unnecessarily tighter capital regulation in the U.S. will increase the cost of lending by U.S. banks while diminishing their ability to compete with their foreign competitors.

A Comparison of U.S. and European Large Bank Risk-Based Capital Requirements

Large, internationally active banks are all subject to capital requirements that are informed by internationally negotiated standards and are set forth by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. Capital is a critical resource for banks, ensuring that they can absorb losses associated with lending, other services, and changes in the economy. But capital is an expensive form of bank funding. The Basel committee was formed in 1975 for the purpose of creating bank regulatory standards that are consistent across member jurisdictions. Once standards are adopted by Basel, each country codifies those standards into regulation at the national level.

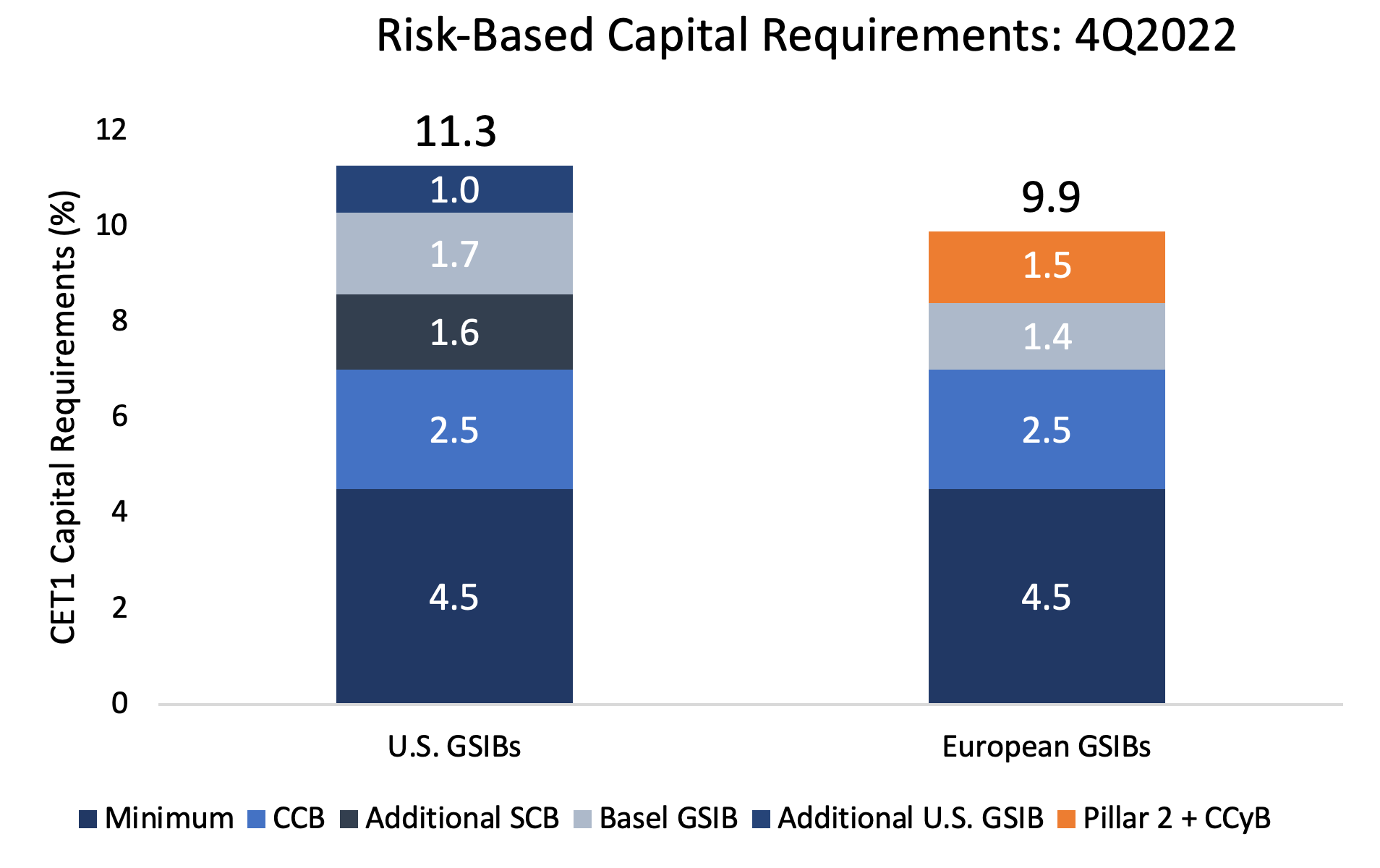

Figure 1 below compares the weighted average risk-based capital requirement – in percentage terms – that applies to the eight members of the Financial Services Forum as well as 12 large banks headquartered in Europe – the UK (3), Switzerland (1), and the European Union (8). Each of these institutions is designated as a Global Systemically Important Bank (GSIB). The figure displays the overall level of required capital as well as the constituent components.

Source: Federal Reserve Y-9C, Company Annual Reports

As shown in the figure, large U.S. banks are subject to a risk-based capital requirement of 11.3 percent versus a requirement of 9.9 percent for large European banks. As Basel capital regulation is intended to create equal standards across jurisdictions, one is led to ask – why are capital standards so much higher in the U.S.?

U.S. capital requirements are higher in the U.S. primarily for two reasons. First, the eight U.S. GSIBs are subject to a higher GSIB surcharge – an additional capital charge for GSIBs – than those in Europe, because the Federal Reserve applied a surcharge that is tougher than the Basel GSIB standard. In the left-hand bar chart, we show that the higher GSIB surcharge (Additional U.S. GSIB) results in an additional 1.0 percent requirement. Second, large U.S. banks are subject to the Federal Reserve’s stress tests, which are then translated into a bank-specific stress capital buffer (SCB). Large U.S. banks are subject to an average SCB of 4.1 percent. Prior to the adoption of the SCB by the Federal Reserve, large U.S. banks were subject to a 2.5 percent capital conservation buffer (CCB) that is prescribed by Basel and applied also to large European banks. As a result, the SCB results in an additional requirement of 1.6 percent (Additional SCB) that does not apply to European banks.

It should be noted that large European banks are subject to an additional set of Pillar 2 capital requirements that are not applied to U.S. banks. Still, the punitive nature of both the U.S. GSIB surcharge and SCB result in required capital for large U.S. banks that is 1.4 percentage points higher than that required of large European banks. In dollar terms, U.S. GSIBs are required to hold $100 billion more capital than their European competitors due to these more stringent requirements.

A Comparison of U.S. and European Large Bank Equity Capital Levels

An analysis of U.S. and European capital standards is informative, but how do these different capital standards translate into the amount of equity capital maintained by large U.S. and European banks? After all, banks typically maintain equity capital beyond their regulatory requirements to have a prudent cushion, and they consider a host of other factors, such as market conditions and the state of the economic cycle, in determining how much equity capital to maintain on their balance sheets.

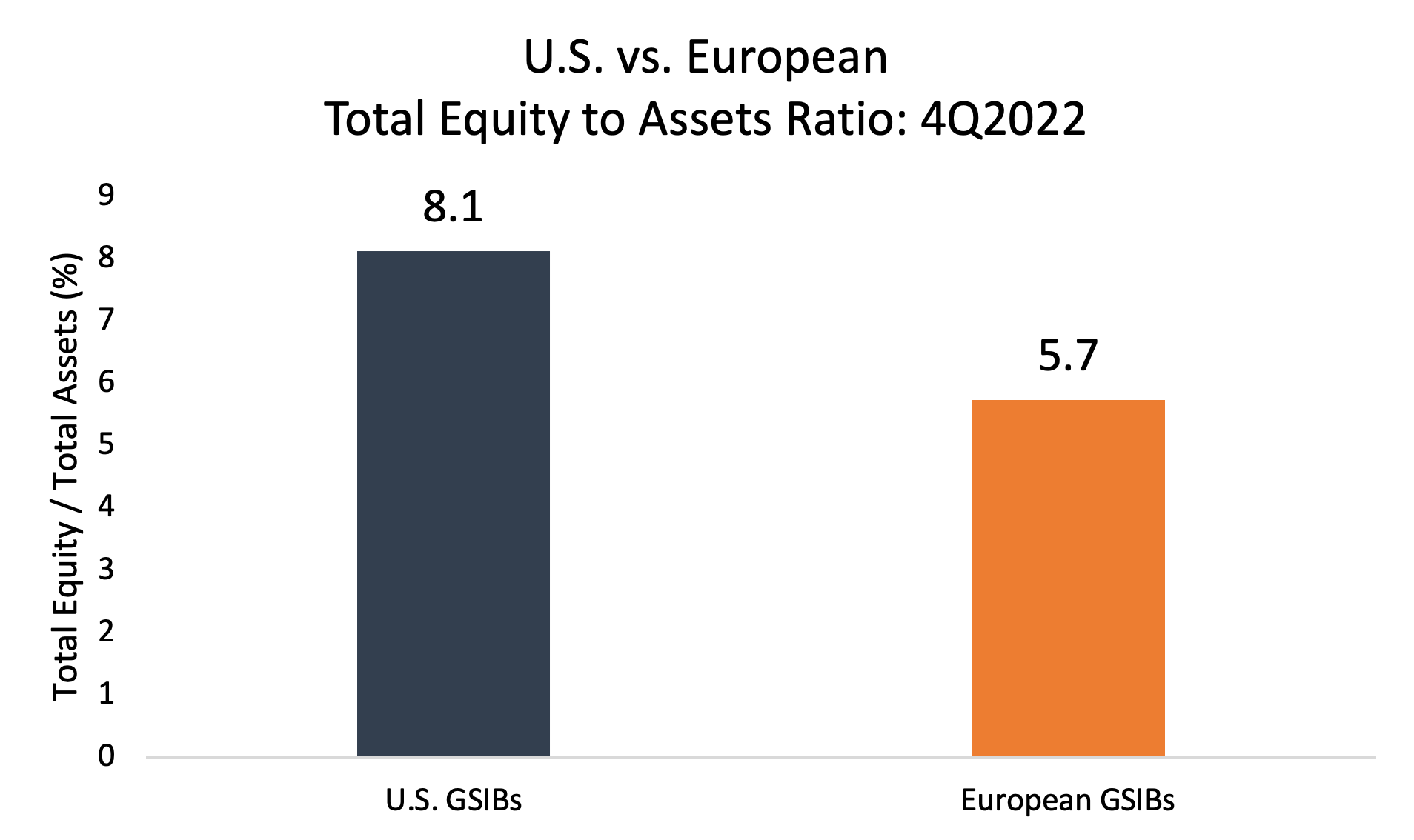

Figure 2 displays the ratio of equity capital (Total Assets – Total Liabilities) to total assets for large U.S and European banks. These ratios account for well-known, but technical differences in how U.S. and European banks report their total assets. Also, these ratios are based on total asset measurements that do not account for risk. As a result, these ratios cannot be directly compared to the risk-based requirements described above, but are informative for assessing the overall amount of equity maintained by each group of banks.

Source: Federal Reserve Y-9C, Company Annual Reports

As shown in the figure, U.S. GSIBs maintain 8.1 percent of total assets in equity capital as opposed to 5.7 percent for large European GSIBs. This clearly demonstrates that the higher requirements set by U.S. regulators directly translate into higher amounts of equity capital maintained by large U.S. banks.

The Further Tilting of the Unlevel Playing Field

As we have documented, large U.S. banks are subject to more stringent capital requirements and maintain more equity capital on their balance sheets than large European banks. This disparity directly contributes to competitive inequity because banks with lower capital requirements can fund their lending cheaper and undercut banks subject to more stringent requirements.

The central aim of Basel III Finalization was to increase the quality and quantity of European bank capital to improve the competitive landscape. However, the European Union is proposing to implement these reforms in a manner that deviates from the Basel standards. More specifically, the European Banking Authority estimates that the EU approach will result in 3.2 percentage points less capital than would be achieved if the reforms were implemented in line with the Basel agreement.

If the U.S. implements Basel III Finalization in a way that is more stringent than that adopted by the EU, the competitive inequities will be worsened, and there will be significant and unnecessary costs to the U.S. economy. In particular, the cost of bank lending by U.S. banks will rise while eroding their ability to compete with their foreign competitors. U.S. regulators can implement the standards in a way that avoids these results. And given the obvious strength and resilience of the largest U.S. banks, it has every reason to do.