Introduction

Recently, bank regulators issued a proposal to modernize the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) after the Federal Reserve publicly committed to do so in 2021. The proposal contains an economic analysis showing that the impact of the proposal on institution-level capital is de minimis – required capital for all affected institutions would decline by less than two percent. One part of the economic analysis showed that narrow, bank subsidiary-level capital requirements would decline by a larger amount. The identified decline in narrow, bank subsidiary-level capital requirements has been cited by some to argue that the proposal would significantly weaken capital requirements. This interpretation confuses broad, institution-level capital requirements with narrow, bank subsidiary-level requirements and fails to understand how the two requirements relate to each other – both in theory and in practice. In this blog, we review the difference between institution-level and bank subsidiary-level capital requirements, discuss the economic relationship between these requirements, and empirically demonstrate that a reduction in bank subsidiary-level requirements not matched by a similar decline in institution-level requirements has no meaningful impact on an institution’s capital or resiliency.

Bank Holding Companies (BHCs) and Banks

What exactly is Bank of America? For that matter what exactly is JPMorganChase or Wells Fargo or any other large “bank” that people regularly engage with on a daily basis? Most people would likely respond – “well, I guess Bank of America is a bank.” And that’s right – sort of. Bank of America is actually a bank holding company, or “BHC.” The full name of “Bank of America” is actually Bank of America Corporation. Bank of America Corporation (BAC) is a large and diverse holding company that contains a bank (Bank of America, National Association, or “BANA”), a securities dealer (BofA Securities), an asset manager (Merrill Lynch), and a variety of other operating companies and subsidiaries that work in tandem to bring households, communities, and businesses a diverse range of important and valuable financial services.

Why does this – admittedly Jeopardyish – technical distinction matter? It matters because the financial health and resilience of “Bank of America” refers to the health and resiliency of the entire corporation and not just “the bank.” Moreover, the holding company maintains capital that supports the resilience of the entire organization. When media outlets, bank analysts and others report on “the earnings of Bank of America,” “the capital of Bank of America,” or “the share price of Bank of America,” they mean the earnings, capital, and share price of the entire corporation (BHC) because that is the most comprehensive and economically relevant institution.

BHC and Bank Capital Requirements

Bank holding companies are regulated by the Federal Reserve. Banks are regulated at the Federal level by one of three regulators – the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Reserve, or the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Bank of America, National Association (BANA), for example, is regulated by the OCC.

The Federal Reserve establishes capital requirements for all BHCs (Bank of America Corporation). Bank regulators establish capital requirements for banks (Bank of America, National Association). In general, the Federal Reserve’s BHC capital requirements are larger and significantly more stringent than bank subsidiary-level capital requirements set by bank regulators.

For example, as of the first quarter of 2025, Bank of America Corporation had total assets of $3.3 trillion. In the same quarter, Bank of America, National Association, maintained total assets of $2.6 trillion. The Fed’s BHC capital requirements apply to all $3.3 trillion in assets while the bank subsidiary-level capital requirements only apply to the $2.6 trillion of assets on the balance sheet of the bank. Accordingly, BHC capital requirements are broader, institution-level capital requirements that support the safety and soundness of the entire financial institution.

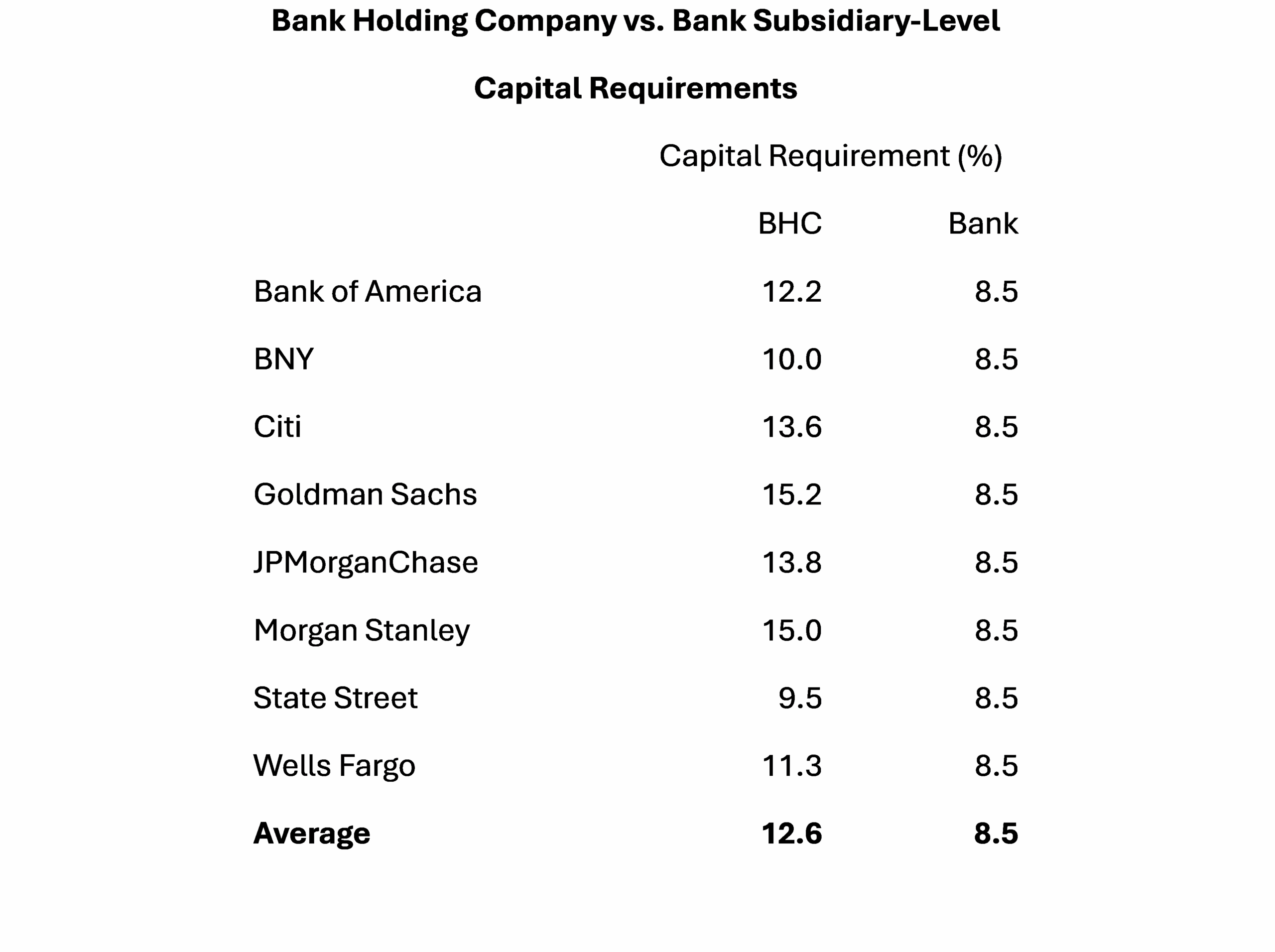

To further demonstrate the difference in bank holding company and bank subsidiary-level requirements, all banks are subject to a bank subsidiary-level (Tier 1) capital requirement of 8.5%, while BHC (Tier 1) capital requirements vary based on factors such as the result of the Federal Reserve’s annual stress test. The table below shows the difference between BHC and bank subsidiary-level capital requirements for Financial Services Forum members.

Reviewing the table shows that Forum members are subject to significantly stricter capital requirements at the BHC level than at the bank subsidiary-level. On average, Forum members are subject to a capital requirement that is roughly four percentage points higher at the BHC level (12.6% vs 8.5%).

What does this mean exactly? Imagine a BHC that only contained a bank. If the bank had total assets of $100, the BHC would be required to maintain $12.60 in capital while the bank would be required to maintain $8.50 in capital. Ultimately, how much capital is actually required? The institution must maintain the higher of the two amounts – $12.60. And herein lies the rub. When bank subsidiary-level capital requirements are eclipsed by stricter and more stringent BHC capital requirements, the bank subsidiary-level requirements become considerably less relevant.

An analogy is of some use to fully contemplate the economic mechanism at play. Imagine that as a teenager you want to stay out late after Homecoming. Suppose Dad is a softie, and Mom lays down the law at home. Suppose further that Mom has a strictly enforced curfew of midnight while Dad will look past a return to the homestead in the wee hours of the morn’. Now imagine working over Dad before Homecoming and ultimately he relents and agrees that returning home at 1 a.m. is OK. Does this help? Not if Mom holds firm at a midnight curfew. The issue is exactly the same in the world of bank capital. Reducing a bank subsidiary-level capital requirement is of limited relevance if the more stringent BHC requirement is unaffected.

Pointing to lower bank subsidiary-level capital requirements as a sign of a weaker capital regime is misleading because it ignores the important interplay between BHC and bank subsidiary-level requirements. It similarly ignores the fact that, for large banks, BHC capital requirements are more stringent, rendering reductions in bank subsidiary-level requirements considerably less relevant.

BHC and Bank Subsidiary-Level Capital – What Do the Data Show?

The discussion above makes the economic case for why a narrow focus on bank subsidiary-level requirements that ignores broader institution-level capital requirements is misguided. But what do the data say? Ultimately, we should corroborate the conceptual economic case with real world data.

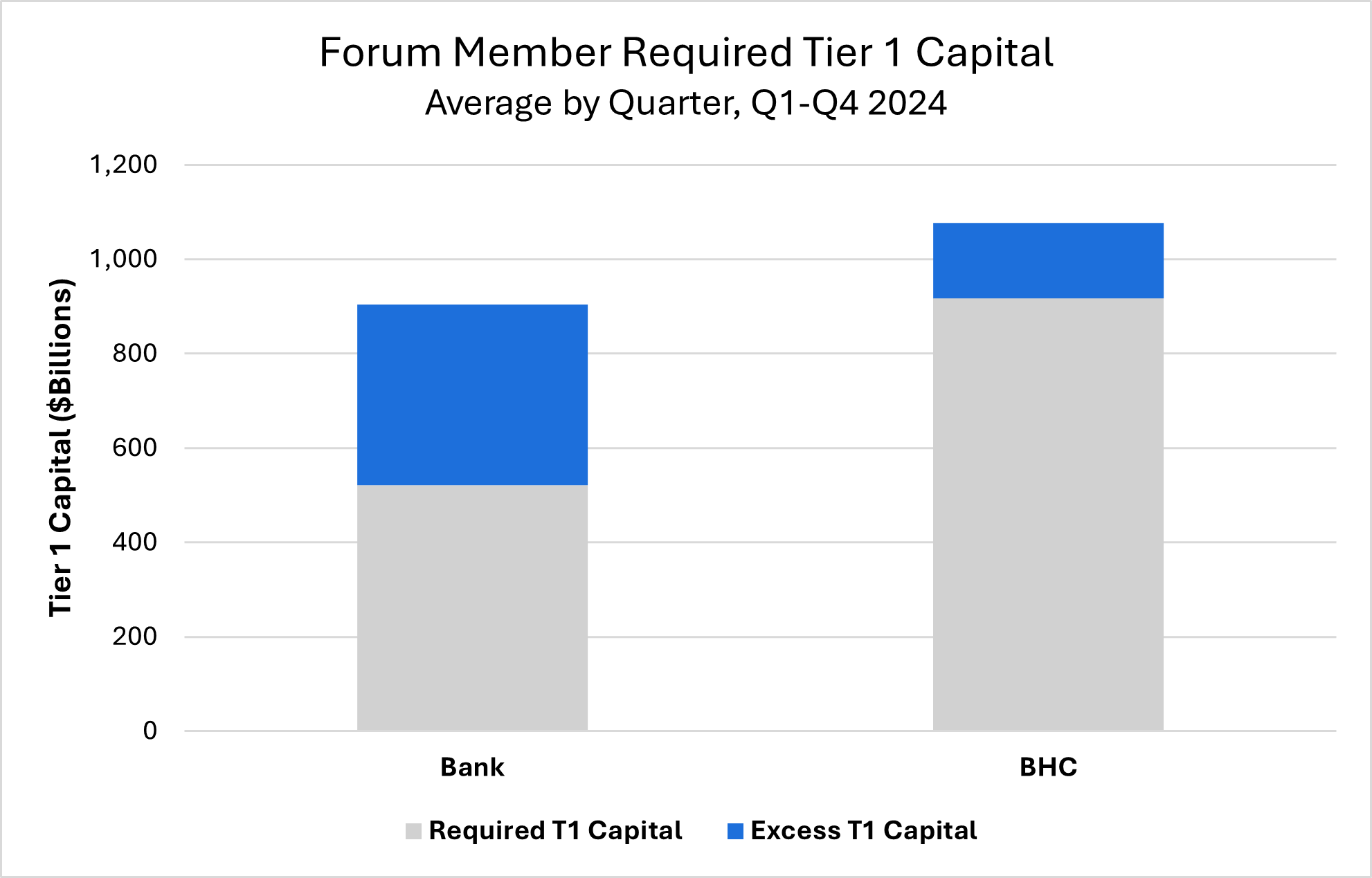

Consider the chart below that depicts aggregate (Tier 1) capital requirements at the BHC and bank subsidiary-level for Forum members. Each bar shows the requirement (grey) and the excess capital above and beyond the requirement (blue). At the narrow bank subsidiary-level, in 2024, Forum members maintained $914 billion in capital (grey+blue). The bank subsidiary-level requirement was – a much lower – $525 billion (grey). In aggregate then, Forum members were maintaining excess capital at the bank subsidiary-level of roughly $400 billion. At the broader BHC level, Forum members maintained roughly $1.1 trillion in capital while the BHC requirement was roughly $926 billion. In aggregate, Forum members maintained excess capital at the BHC level of roughly $175 billion.

A few things about this data are worth noting. First, as discussed, both capital maintained (grey + blue) and capital required (grey) are substantially higher at the BHC than at the bank. Second, and importantly, at the bank subsidiary level, banks are maintaining a significant amount of excess capital over and above the requirement of nearly $400 billion. At the BHC level, the amount of excess capital is much more modest at less than $200 billion.

What explains the large difference in excess capital at the bank and BHC? Why, for example, doesn’t the bank simply reduce its excess bank subsidiary-level capital from $400 billion to, say, $100 billion? The answer is that doing so would run afoul of the stricter BHC requirement. Accordingly, banks regularly maintain significant excess capital at the bank subsidiary level to comply with stricter and more relevant BHC-level capital requirements.

Conclusion

Robust capital standards are an important safeguard for our financial system’s safety and soundness. The Federal Reserve’s recent proposal to modernize the Supplementary Leverage Ratio will not have an appreciable impact on institution-level bank capital. Claims that the proposal weakens bank capital standards are misguided because they conflate bank subsidiary-level and BHC capital standards and fail to recognize the important economic relationship between the two standards. BHC-level capital is a financial resource that supports the resilience of all the activities undertaken by the BHC. BHC-level requirements are more comprehensive and generally more stringent than bank subsidiary-level requirements. Accordingly, a narrow focus on bank subsidiary-level requirements is inappropriate when evaluating the health and safety of the banking and financial system.