Introduction

Climate change is garnering considerable attention from financial policymakers. As an example, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) recently released a report on climate-related financial risk. Additionally, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) recently released principles on the management and supervision of climate-related financial risks. Increasingly, many policymakers are focused on the need for large banks to improve and demonstrate their methods of addressing climate-related financial risks. Consequently, it is important to consider the type and nature of climate-related financial risks borne by large banks. In this post, we review some recent data and analysis that are informative on the nature of climate-related financial risks for large banks. The data suggest that large banks are less exposed to climate-related financial risk than the banking sector as a whole, and may, in fact, perform well in response to some forms of climate risk as a result of increased lending activity. These data are not the last word on climate-related financial risk for large banks, but they are relevant and should be carefully considered as policymakers consider the management of climate-related financial risks by large banks.

Evidence from European Banks

The European Central Bank (ECB) recently undertook an analysis to assess the impact of climate change on financial risk using data from 1,600 European banking groups of varying sizes. The analysis was conducted by ECB staff using granular, bank exposure data, and the ECB’s models and assumptions regarding how climate change influences risk.

One noteworthy analysis models the impact of transitioning to a “hothouse world” on the credit risk –or average default probability – in bank lending portfolios. The “hothouse world” is a specific climate scenario provided by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) – a group of global central banks working on the development of environment and climate risk management in the financial system. This scenario represents an extreme worsening of climate change in which global temperatures increase by 3 degrees Celsius by 2080 and GDP falls by as much as 22 percent over the same period.

The ECB analysis considers the average default rate in bank lending portfolios under both a less drastic “orderly transition” and the hothouse world. The increase in average default probability between the orderly transition and hothouse world scenarios measures the impact of climate-related financial risk on each bank’s lending portfolio. The results of this analysis are contained in the Figure presented below from the ECB report.

Each dot in the figure represents a specific bank’s loan portfolio. The size of the dot represents the size of the bank’s exposure with larger dots representing larger banks with larger loan portfolios. The red dots represent European Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIBs). European GSIBs are most directly comparable to U.S. GSIBs (all of which are FSF members). The blue and yellow dots represent small and mid-sized European banks. The dotted line in the figure represents the 45-degree line. Any dot that lies on the 45-degree line represents a case in which the bank’s average default probability is the same under both the orderly transition and hothouse scenarios. A dot that lies below the 45-degree line represents a case in which the bank’s average default probability increases in the hothouse world scenario, which suggests that a worsening climate poses an increased financial risk to that institution.

The data in the figure reveal a few interesting characteristics about large bank loan portfolios and the impact of a worsening climate on large bank financial risks. First, European GSIBs display average default probabilities that are generally below average and present less financial risk in both scenarios. This can be seen by noting that the red dots are clustered to the left and below the solid lines labeled “Average.” Second, the European GSIB data are relatively close to the 45-degree line suggesting that any increase in default probabilities in the hothouse scenario is small. Third, to the extent that some banks exhibit a noticeable increase in default probability in the hothouse scenario – indicated by a dot that lies well below the 45-degree line – these banks are of smaller size and systemic importance within Europe (the blue dots).

Overall, these data suggest that large European GSIBs maintain loan portfolios that are relatively low risk and are not subject to significant amounts of climate-related financial risk. Some smaller and mid-sized banks, however, do exhibit noticeable increases in default risk resulting from the hothouse scenario. While we cannot assert that the experience of European GSIBs will translate directly to U.S. GSIBs, large banks share some common characteristics, such as broad and diversified lines of business and significant capital markets activities, that may suggest at least a degree of commonality in the impact of climate risk on default probabilities.

Evidence from U.S. Banks

As discussed, the European experience may not directly translate to U.S. banks. However, some recent research from economists at MIT and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York examines the potential impact of climate risks on U.S. banks. This research examines the impact of weather disasters such as hurricanes and floods on bank capital and performance.

The authors find, over the 1995-2018 period, that extreme weather events have no discernible negative impact on bank capital or performance. As stated by the authors, “[w]hen we consider all FEMA disasters, we find generally insignificant or small effects on bank performance and stability.” Additionally, the researchers also find that larger banks tend to exhibit stronger performance following a severe weather event because of the high volume of subsequent lending activity. Interestingly, the authors argue that larger banks respond by increasing lending following a weather event because they have access to deposits in affected and unaffected areas and can effectively channel resources from locations with surplus savings to locations that need to borrow funds to recover from a weather event. Accordingly, large banks’ geographically diversified funding model is beneficial to both themselves and the communities that they serve.

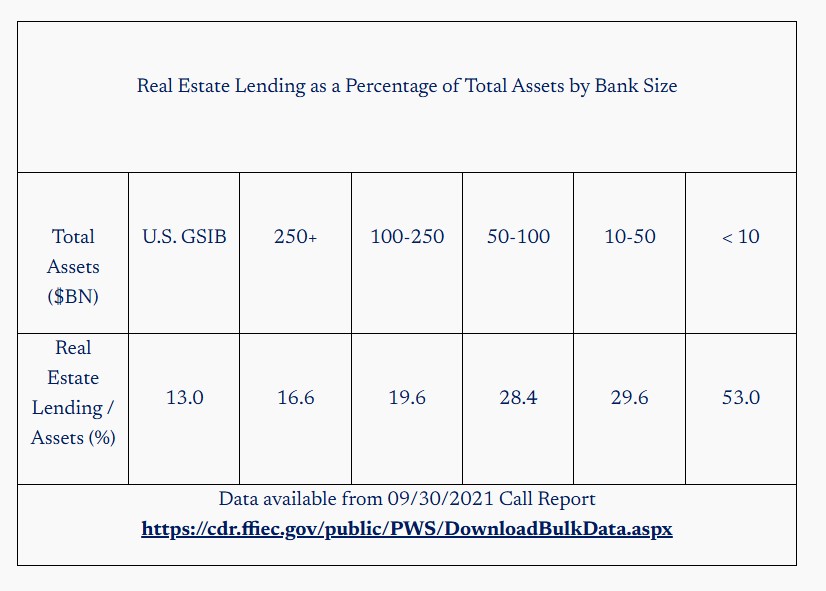

Finally, in considering why large banks may be well positioned to address climate risks, it is useful to consider the kinds of assets that are most likely exposed to climate risk and their concentration in large bank asset portfolios. Climate events such as rising sea levels, hurricanes, and floods are most likely to impact real estate assets such as hotels, commercial buildings, and homes. As a result, banks with large concentrations in real estate-backed loans are more likely to be exposed to climate-related financial risks. The table below shows the fraction of bank assets invested in real estate-backed loans for banks in different size categories.

Conclusion

Climate change and its impact on our environment and economy is an important public policy issue that deserves careful consideration. Existing data and research suggest that large banks are better positioned to deal with climate change than the sector as a whole. At the same time, large banks are actively assessing these risks and taking necessary steps to manage and mitigate climate-related financial risk. Accordingly, as policymakers consider the role that large banks should play in addressing climate-related financial risk, they should carefully assess the type and significance of climate-related financial risks borne by large banks. A balanced and data-based approach to addressing climate-related financial risks will best ensure that we maintain a robust, safe, and sound banking system.