Introduction

Since the financial crisis, regulators have dramatically tightened the large bank regulatory regime by substantially increasing capital, liquidity, and resolution requirements. These changes have had a significant impact on the public’s perception that large banks are “too big to fail” or “implicitly guaranteed.” Recently published, data-driven, academic research supports this conclusion and finds that “the simplest explanation of the data is that, after the GFC [great financial crisis], wholesale creditors of large US banks have lowered their expectations of bailouts.” In this blog, we briefly review the findings of this research and lay out the clear and convincing rationale for the findings.

What the Research and Data Show

Recently, economists at Stanford University and the Australian National University published a paper “The Decline of Too Big to Fail” in the Journal of Finance – academia’s preeminent finance journal.

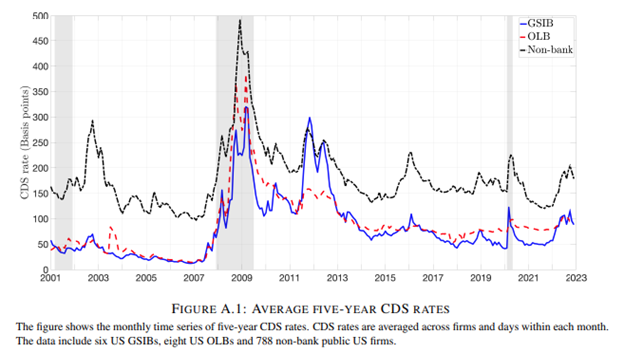

The paper examines the cost of purchasing insurance against the default of a U.S. Global Systemically Important Bank (GSIB) in the credit default swap, or “CDS,” market over the 2001-2022 period. The primary data source that drives the paper’s finding is re-produced below.

The cost of insuring against the default of a U.S. GSIB is shown by the blue line in the chart. A higher level of the CDS rate implies that it is more expensive to insure against the potential default of a U.S. GSIB. As shown in the figure, relative to 2007 the cost of insuring against the default of a U.S. GSIB in the CD market has increased substantially from roughly 0.25 percent in 2007 to roughly one percent in 2022 – a four-fold increase.

Investors demand a higher premium to insure against default either because they believe that: 1) the likelihood of default has increased or 2) the loss in the event of a default has increased. Accordingly, the data in the figure necessarily imply that either the likelihood of default for U.S. GSIBs or the loss in the event of a U.S. GSIB default has increased. On this fundamental point the data are clear and incontrovertible.

At the same time, regulators have substantially reduced the probability of a GSIB default since the financial crisis because the large bank regulatory regime has been dramatically tightened. In particular, U.S. GSIBs are subject to significantly higher capital requirements, liquidity requirements, resolution requirements, as well as a variety of other regulatory and financial market reforms that have substantially reduced risk in the banking system.

The table below demonstrates this fact by detailing the increase in capital, liquid assets, and total loss absorption capacity (TLAC) from before the crisis until now.

|

Explicit Prudential Safeguards: Pre-Crisis to Current Day |

|||

| Pre-Crisis | Current | % Increase | |

| Capital | 297BN | 997BN | 236% |

| Liquidity | 1.0TN | 3.4TN | 240% |

| TLAC | 851BN | 2.0TN | 135% |

As shown in the table above, capital, liquidity, and total loss absorbing capacity (all forms of equity and long-term debt that can be “bailed in” during a default event) have all increased significantly since the crisis.

Accordingly, it is not possible to conclude that the likelihood of a U.S. GSIB default has increased. To the contrary, the data and evidence clearly suggest that U.S. GSIBs are stronger, more resilient and less likely to experience a default event today than they were before the financial crisis.

Accordingly, the authors conclude that the resulting rise in the CDS rate reflects an increase in the expected loss from a default event. The authors further reason that the resulting increase in expected default losses reflects a substantial decline in any perceived “bailout” in a crisis. Specifically, they find that, “without a post-GFC drop in creditor-perceived probabilities of a government bailout, we might expect large-bank wholesale credit spreads to have reverted substantially closer over time to their pre-GFC levels, given general improvements in large-bank capital buffers. That is not what we find, not even after allowing for changes in insolvency risk premia. It seems that the simplest explanation for the data is that, after the GFC, wholesale creditors to large US banks have lowered their expectations of bailouts.”

Conclusion

The regulatory regime that applies to large banks has undergone a complete transformation since the financial crisis. This transformation has created and strengthened an array of explicit safeguards, which concretely and credibly reduce the perception that large banks would be “bailed out” and benefit from “implicit guarantees.” As the data clearly show, bank funding costs have risen, not fallen, since before the crisis. Data-driven, peer-reviewed, academic research has shown that the observed increase in funding costs, coupled with the significant increase in capital and other prudential safeguards imply a material weakening of any “implicit guarantees” for large banks.