Introduction

Over the past decade, regulators have taken steps to disincentivize the use of short-term wholesale funding (STWF) by large banks. This regulatory initiative has been driven by concerns that STWF is systemically risky. The chief concern is that if short-term creditors stop extending short-term debt, large banks would be forced to quickly liquidate illiquid assets at “fire-sale” prices that would create large losses and impose large costs on the rest of the economy. This concern fundamentally rests on the assumption that short-term funding is used primarily to finance long-term, illiquid assets. New research from economists at the Federal Reserve Board and the University of Chicago, however, demonstrates that the role played by STWF in the banking system has changed significantly over the past decade. Specifically, they find that large banks increasingly use short-term wholesale funding to finance low-risk, liquid assets, such as bank reserves, that can be liquidated quickly without taking losses or impacting the rest of the financial system. These findings show that STWF presents a lower level of risk to the financial system and suggests regulators should reconsider how STWF is addressed by financial regulations, such as the GSIB surcharge.

Short-Term Funding and Asset-Liability Management

A key point made in the new research is that the amount of short-term funding, all by itself, does not generate systemic risk. Rather, what matters is how the short-term liability is managed on the asset side of a bank’s balance sheet. Specifically, imagine a situation in which a bank raises $100 in short-term funding – say through the issuance of short-term debt – and then invests that $100 in cash. Now suppose that once the short-term debt matures, short-term creditors are unwilling to re-extend or “roll” the same short-term credit to the bank. In this case, the bank simply repays the creditors with the $100 in cash that it has on hand. Repaying the existing creditors with cash does not result in any losses to the bank or to the creditors and does not impose any spillover costs on the economy. In this case, the use of short-term debt creates no financial stability risk because the short-term maturity of the debt is matched with a liquid asset – cash. As the authors themselves state, “global banks have become more resilient to negative wholesale funding shocks, as they can swiftly reduce their arbitrage positions in response to wholesale funding dry-ups.” In this context, the authors use the term “arbitrage” to refer to situations in which global banks invest funds in liquid assets, such as bank reserves, that pay a rate of interest marginally higher than the rate of interest they pay on the short-term funding.

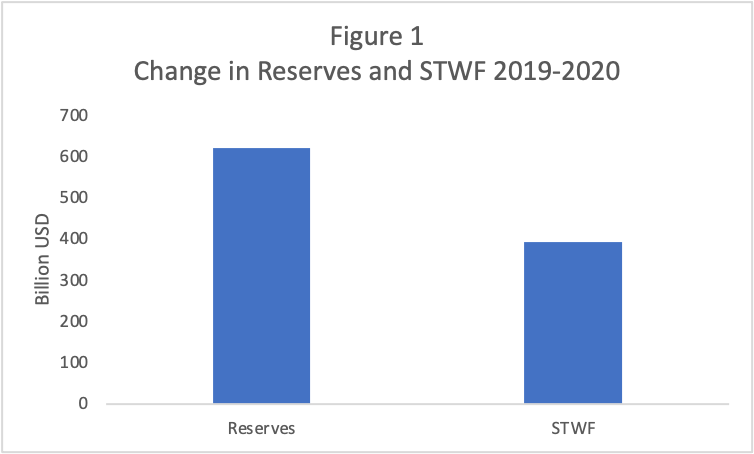

This state of affairs, in which large banks increasingly invest short-term funding in low-risk and liquid assets became increasingly important over the course of 2020 as the Federal Reserve expanded its balance sheet from roughly $4 trillion to $7 trillion. Figure 1 below shows the increase over 2020 in bank reserves and short-term wholesale funding for the eight Financial Services Forum members.

As can be seen in Figure 1, while total STWF rose for Forum members, so too did bank reserves. What’s more, the increase in bank reserves more than offsets the increase in short-term funding. As a result, the potential risks associated with STWF were largely attenuated for the reasons cited by the Federal Reserve and University of Chicago researchers – each dollar of STWF was matched against a low-risk and liquid asset that could be used to repay short-term creditors at any time.

Short-Term Wholesale Funding and Financial Regulation

The level of STWF employed by FSF members has a direct impact on the level of their GSIB surcharge – an additional capital buffer required by the Federal Reserve that only applies to Global Systemically Important Banks, or GSIBs. As STWF levels rise, so too do does their GSIB score, which then results in a higher GSIB surcharge.

As this new research and the data in Figure 1 show, recent changes in the way that STWF is used and managed by large banks suggests that this relationship should be reconsidered. Over the course of 2020, increases in STWF were largely offset by holdings of bank reserves, which pose no risk to the banking sector and can be liquidated quickly to repay short-term creditors. Accordingly, the observed increase in STWF over 2020 does not automatically represent an increase in systemic risk that should be impounded into the GSIB surcharge. More broadly, and over the long term, the way in which STWF is used and managed by large banks has clearly changed. As the role of STWF in the banking system changes, so too should its role in financial regulations, such as the GSIB surcharge. Accordingly, the Federal Reserve should consider this new research and how its findings would impact the way STWF determines GSIB surcharges.

Conclusion

Short-term wholesale funding is viewed by regulators as a source of systemic risk. As a result, financial regulations, such as the GSIB surcharge, have been designed to dis-incentivize its use. The argument that STWF is systemically risky rests on the assumption that the proceeds from STWF will be used to fund long-term, illiquid assets that would be difficult to liquidate if short-term creditors refuse to continue extending short-term funding. New research shows that the way in which the banking sector utilizes STWF has changed significantly over the past decade. Namely, STWF is increasingly used to invest in short-term, liquid assets such as bank reserves that can be easily liquidated to repay short-term creditors. As a result, the risks posed by the use of STWF have declined significantly. The changing risks of STWF should be considered by regulators in the context of financial regulations that dis-incentivize its use, such as the GSIB surcharge.