A recent working paper by Lawrence Ball of Johns Hopkins University calls into question the liquidity levels of six, large U.S. banks. In this post we respond to the claims made in the paper and provide additional data and research-based assessments of large bank liquidity that run counter to the claims made in the working paper. These analyses point to robust liquidity levels at large U.S. banks. Specifically, one sophisticated and data-based estimate points to a low level of large bank liquidity risk that has continued to decline during the current pandemic period.

The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Modified LCR Assumptions

The LCR is a key liquidity regulation that requires large banks to maintain liquid assets such as cash and U.S. Treasury securities in an amount at least as large as the expected cash outflows that would occur for different types of liabilities over a 30-day horizon as prescribed by the LCR rule.

The paper correctly notes that the speed with which each type of liability is expected to runoff – “runoff rates” – over a 30-day horizon is determined by regulators within the LCR rule. The paper also correctly notes that these assumptions are generally not supported by any transparent data-based analysis.

The paper then takes issue with three specific runoff rates as being “too low.” Specifically, it takes issue with the runoff rates for:

- Retail deposits

- Secured funding (repurchase, or “repo,” agreements)

- Derivative outflows (collateral calls)

The paper then proceeds to substantially increase each of the above runoff rates, recomputes the LCR for six, large U.S. banks, and reports the results.

Critique of the Analysis

The main result presented in the paper that large bank LCRs decline in response to the adjusted runoff rates is simply a matter of arithmetic and much less of a research finding. Put simply, if you take the LCR rule and increase a few selective runoff rates, then the resulting LCR must rise and the amount of excess liquidity must fall.

The analysis presented in support of the modified LCR are problematic for three reasons.

- The analysis is one-sided and considers a small number of cherry-picked runoff rates that are deemed to be “too low” without any consideration of runoff rates that may be “too high.”

A thorough reconsideration of the LCR would be a welcome addition to the research literature on bank liquidity regulation, but any such analysis should consider both runoff rates that may be too high as well as those that may be too low. As mentioned previously, increasing a few arbitrarily selected runoff rates is far from a serious consideration of the entire LCR rule and leads to rather predictable results. What’s more, there is evidence that some LCR runoff rates are implausibly high and do not comport with data and experience during the crisis. As a specific example, the 40% runoff rate for some affiliated brokered sweep deposits are significantly higher than that suggested by the crisis experience. Moreover, the evidence underlying this concern is based on crisis data and experience. Accordingly, an analysis that focuses on a small number of selected runoff rates deemed to be too low without a broader and more even-handed examination of all of the LCR’s key assumptions does not represent a serious, empirical reconsideration of the LCR. - The comparisons to the crisis experience of the specific financial institutions that underlies the paper’s adjusted runoff rates is an apples-to-oranges comparison that is not appropriate. The paper compares the crisis experience of several financial institutions that were not banks or bank holding companies, not directly regulated by the Federal Reserve, and not subject to the host of capital and liquidity regulations that are in effect today. These comparisons simply do not make sense in light of these significant differences. While it is appropriate to consider the experience of the crisis in terms of market events and financial developments, it is not appropriate to assume that financial institutions with a completely different financial and regulatory structure would behave similarly. Perhaps the most egregious example in this regard is the author’s comparison to AIG in the context of the derivative outflow runoff rate. By now it is well known that AIG was a one-way seller of CDS protection in the lead up to the financial crisis. Large banks are two-way financial intermediaries that connect buyers and sellers of financial instruments and do not maintain significant one-way exposures. Any comparison between the behavior of AIG and regulated bank intermediaries is wholly inappropriate for this fundamental and well-understood reason.

- The analysis underlying the modified runoff rates is idiosyncratic and does not reflect a substantial data-based analysis. The author’s justification for raising the runoff rates for retail deposits and secured funding is based on the isolated experience of one or two financial institutions during the crisis. Any reconsideration of LCR runoff rates should consider the entirety of the crisis experience and not one or two examples – even if they are important examples. Good empirical analysis takes a broad view of all the available data and actively avoids being led astray by a small number of influential data points. In the case of the derivative outflow rates, the paper clearly acknowledges that the data that would be required to seriously assess its magnitude are not generally available. Yet, the author presses on because, in his estimation, the runoff rate is too low and so he settles on increasing the derivatives runoff rate by 100% because “100% is a round number, and it does not strike me as obviously too high or too low.” While we are all welcome to our own opinion, a serious analysis of large bank liquidity should be subject to stricter standards of analysis.

Recent Developments in Large Bank Liquidity

Despite the shortcomings of the paper’s analysis, it is appropriate to consider the state of large bank liquidity in light of its overall importance and relation to financial stability in the current times. Objective data and analysis point to strong liquidity among large banks including the six banks considered in the paper’s analysis. Specifically, consider the following three observations.

First, the banking agencies recently finalized the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR), which will require large banks (the six large banks considered in the author’s analysis and three other large banks) to comply with a new and separate liquidity requirement that will serve to increase the stringency of liquidity regulation for large banks.

Second, the Federal Reserve’s recent Financial Stability Report makes special mention of the significant liquidity position of large banks. Specifically, the report states that “banks continue to have high levels of liquid assets and stable funding.” More to the point, the report shows a chart of bank liquid assets as a fraction of total assets. This chart (reproduced below) clearly shows that Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIBs) — the six banks considered by the author are GSIBs — maintain the highest share of liquid assets, which is North of 25 percent.

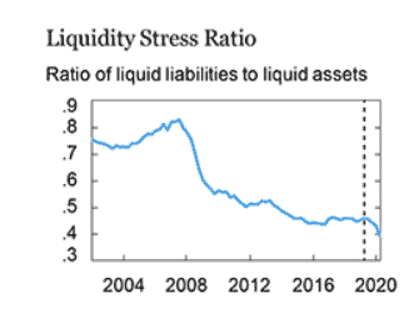

Third, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) have developed a detailed and quantitative model of liquidity risk that they apply to the largest 50 banks in the U.S. This model is sophisticated and deals with differences in banks’ liquidity profiles and business models in a way that can’t be addressed by the simpler analysis presented in the Federal Reserve’s Financial Stability Report. The FRBNY economists estimate large bank liquidity risk over the 2002-2020 period. A plot of their liquidity risk measure is presented below.

As shown in the plot, liquidity risk at large banks has exhibited a secular downward trend since 2008 and has even declined further in 2020. The current level of large bank liquidity risk is at an all-time low. Taken together, these three pieces of evidence suggest that large bank liquidity is robust and has only become more so recently.

Conclusion

Sufficient liquidity for large financial institutions is critical to their soundness and to their ability to serve the economy. The past decade has seen a significant increase in large bank liquidity levels and large bank liquidity regulation. None of these regulations, including the LCR, is perfect but they have surely contributed to a safer and better functioning financial system. The desire to critically reassess the LCR is laudable. Such an assessment, however, should be comprehensive and should be based on extensive analysis that is careful to make informed and meaningful comparisons. The recent working paper discussed here is a one-sided analysis that only considers a handful of cherry-picked assumptions and adjusts runoff rates based on a cursory analysis. Other data and more careful analysis points to the strength and resiliency of large bank liquidity.