Introduction

What happens to the cost and quantity of bank lending when bank capital requirements rise? Among economists, the answer to this question is uncontroversial and informed by fundamental economic theory and rigorous, data-driven analysis. Increasing bank capital requirements increases the cost of bank funding, which is then passed on to borrowers through higher interest rates. Borrowers – both companies and households – then borrow less due to its higher cost. This basic principle is well established and understood by all mainstream economists in the same way that all economists agree that “demand curves slope downwards” – higher prices reduce demand. Of course, economists regularly debate the magnitude of the impact and whether the magnitude varies over time, but the basic premise that raising capital requirements increases the cost of borrowing and reduces lending is not up for debate. In this blog, we briefly review the economic theory behind the idea that increasing capital requirements reduces lending and we point to several recent research papers that quantitatively demonstrate this fact using recent data from the U.S. banking system.

Bank Funding Costs and Borrowing Rates

When a bank makes a loan, it has to charge the borrower an interest rate that covers the cost of procuring the funds that are used to make the loan because “money does not grow on trees.” Banks fund their loans from two sources, 1) debt borrowed from the public largely in the form of deposits, and 2) equity capital from bank investors. It is well known and documented that it is less expensive to procure debt than equity because debt investors are guaranteed to receive their money back before equity investors receive anything. As a result, equity is riskier than debt and commands a premium in the market. Historically, equities tend to earn a rate of return of roughly 10 percent per year. These days, bank deposits earn roughly two percent per year. Accordingly, if a bank takes in $100 in deposits it must pay out $2 per year, but if the same bank issues $100 in equity to investors it will have to pay out $10 per year.

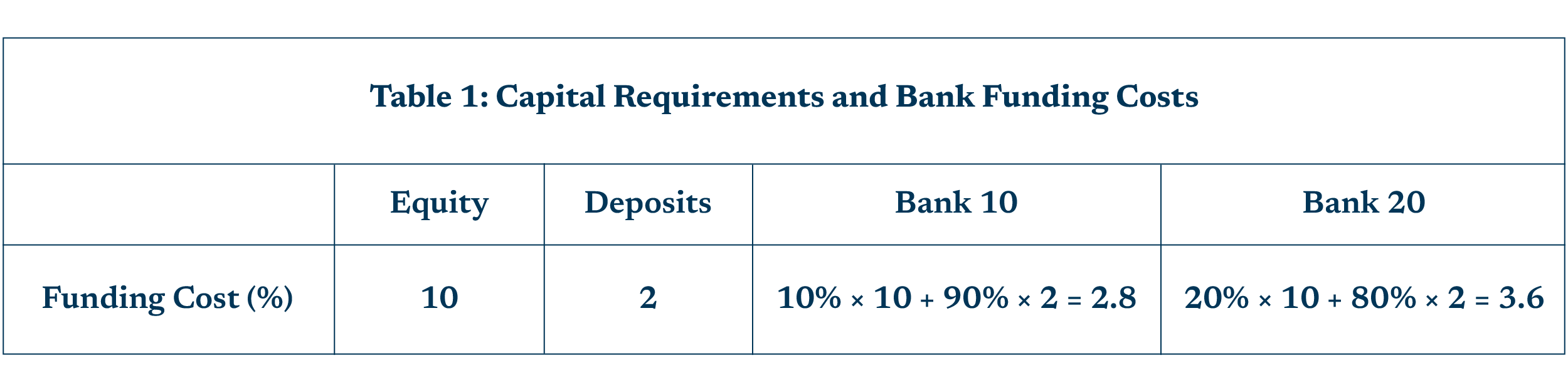

Bank capital requirements dictate how much equity and how much debt (or deposits) a bank must use in funding its lending operations. The table below illustrates the cost of funding at two banks. A bank with a 10 percent capital requirement (Bank 10) and a bank with a 20 percent capital requirement (Bank 20).

As shown in the table above, the bank with the higher capital requirement has a higher funding cost because it is required to use more equity. Accordingly, a bank that is required to maintain a capital requirement of 20 percent would need to charge at least another 0.8% (3.6-2.8=0.8) to a borrower to simply cover the higher funding cost of the loan. This is directly analogous to a car company that is told that it has to use a higher and more expensive grade of steel in building its cars. A higher cost of production translates directly to a higher cost to consumers.

A Common Objection Debunked

The logic of the previous example is often questioned by some who cite the “Modigliani and Miller,” or simply, “MM,” theory of capital structure. The MM hypothesis states that as a company, any company, uses more equity to finance its operations, the debt of the company becomes safer because there is a larger cushion of equity to absorb any losses that improves the protection afforded to debt holders. The MM hypothesis then goes on to demonstrate that under very specialized and idealized conditions that are never met in reality, the reduction in the cost of debt would exactly offset the increased cost of requiring more equity financing. In this highly specialized situation higher capital requirements have no impact on the cost of lending.

Those that cite this theory, however, rarely mention that this result is only true if the following two conditions hold:

- Debt payments are not tax deductible.

- A company’s bankruptcy is costless in the sense that once the bankruptcy occurs the company’s assets can be sold and utilized by other companies with no loss in productivity.

Neither of the above conditions hold in the U.S. economy. Interest payments on debt are tax-deductible and create a valuable “tax shield” and the costs of bankruptcy are significant as can be attested to by anyone who has witnessed the impact of bankruptcy waves on the economy during a recession.

Economists that have studied the MM hypothesis have come to the conclusion that, at best, only about one-half of the reduction promised by the idealized MM theory is realized in practice. In the context of the previous example, this would imply that the bank with higher capital requirements would need to increase the cost of borrowing by 0.4 percent instead of 0.8 percent.

What Does the Evidence Show?

Economics is a great discipline because, out of necessity, it marries theory with empirics. Economists simply have too many competing theories and need to turn to the data to discern which theories best explain the data. So, what does the evidence say about bank capital requirements and bank lending? Thankfully, economists have spent a considerable amount of time studying this issue and there is a lot of research to consider. Below, we briefly cite and summarize a few research papers that well characterize the range of findings in this area.

- One recent paper presents a full-blown macroeconomic model that is estimated using a rich array of data on the U.S. banking system and the economy. A key finding of the paper is “policies requiring intermediaries to hold more capital reduce financial fragility, reduce the size of the financial and non-financial sectors, and lower intermediary profits.” Of course, reducing the size of the financial and non-financial sectors is a direct result of reducing banks’ balance sheet assets (loans), which in turn results in fewer financed assets in the non-financial corporate sector. Interestingly, this paper also finds that pre-crisis capital requirements were “optimal” in the sense that they appropriately balanced increased safety with the lost economic activity that comes from higher requirements.

- Another paper looks specifically at small business lending and finds that banks subject to heightened capital requirements through the Federal Reserve’s stress tests raise the cost of small business loans and provide fewer loans. Specifically, they find that “Banks affected by stress tests reduce credit supply and raise interest rates on small business loans.”

- Finally, a third paper focuses even more specifically at lending to hospitals. The researchers show that the treatment of loans to hospitals in the stress tests increased the effective capital requirement applied to hospital loans. As a result, the researchers find that hospitals faced higher borrowing costs, received fewer bank loans and had to make use of more expensive forms of credit. Specifically, the researchers find that: “Bank stress tests constitute a negative credit shock to their connected hospital borrowers. In particular, we find that loan spreads increase while loan amounts decrease for affected hospitals.” Interestingly, these researchers also find that the need to use more expensive financing had a measurable and negative impact on hospitals and their patients.

These research papers are themselves part of a broader set of academic, data-driven research demonstrating that higher capital requirements raise borrowing costs and depress lending.

Conclusion

Coming to terms with the basic reality that increasing capital requirements reduces lending and economic activity is important in the present situation. Recently, Michael Barr, the Federal Reserve’s Vice Chair for supervision, gave a speech in which he indicated that new capital rules would soon be proposed. In addition, we have recently seen a hefty increase in capital requirements in this year’s round of stress tests and further capital requirement increases are expected in early 2023 as a result of planned increases to the GSIB surcharge. As new rules are rolled out, regulators should carefully consider their overall impact on the economy and economic activity. And that is more so the case when the economy is facing headwinds as is now the case. All banks require robust capital levels to promote a safe and sound banking system and Forum members support strong capital levels. Today, Forum members maintain nearly a trillion dollars in capital, a marked increase over the past several years. At the same time, capital is not a free economic resource and at some point, further increases in capital result in little improvement in safety and mainly depress economic activity.