Introduction

Recently, regulators both inside and outside the U.S. have taken a keen interest in moving forward with additional changes to the large bank capital framework. More specifically, the FDIC recently identified finalizing large bank capital reforms as a key priority and the Chair of the Basel Committee also recently emphasized the need to finalize these reforms. As regulators consider moving ahead with these reforms it is important to put them in an appropriate U.S. context. Towards that end, in this blog we, 1) review the historical development of the reforms as well as how they relate to the current capital position of large banks, 2) review the stated rationale for the reforms, 3) review the important lessons of the past few years, and 4) highlight important distinctions between the U.S. and European regulatory framework that are important to keep in mind to ensure an effective and sensible implementation of any further capital reforms in the United States.

Where Are We and How Did We Get Here? Basel III and Basel III Finalization

The large bank capital framework is a product of international coordination. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) – an international regulatory body comprised of bank supervisors around the globe – works to establish high-level agreements on large bank capital requirements that are then implemented at the national level by each nation’s appropriate bank regulatory authorities. In 2010, in the wake of the global financial crisis, the BCBS published an extensive set of capital reforms, known collectively as “Basel III.” The stated intent of these reforms was to increase both the quantity and quality of capital for large, internationally active banks. The Basel III reforms were implemented in the United States in 2013.

Later, in 2017, the BCBS published a further set of revisions to the large bank capital framework. These additional revisions, known collectively as “Basel III Finalization” have not yet been implemented in the United States or elsewhere internationally. These Basel III Finalization reforms are the specific reforms that are identified by both the FDIC and the BCBS in recent speeches.

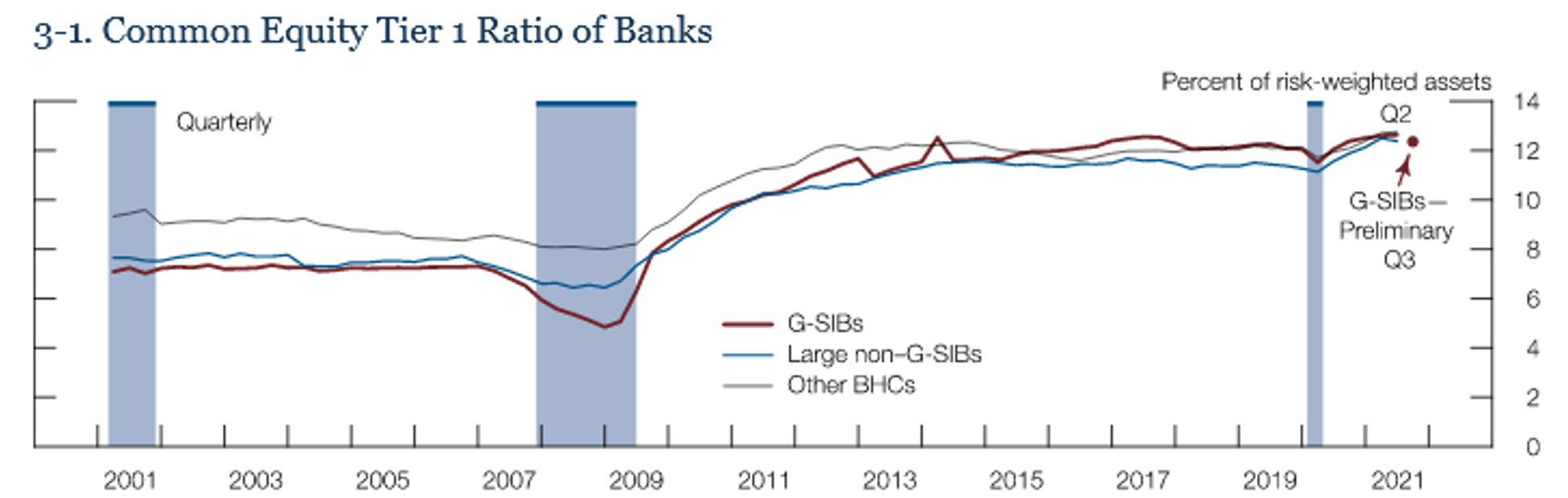

Before delving into the details of Basel III Finalization, it is useful to have some context on large bank capital levels in the United States. In its most recent Financial Stability Report, the Federal Reserve provided an analysis of large bank capital levels that we reproduce below.

As the figure shows, capital levels of Forum members (Global Systemically Important Banks, or G-SIBs) have more than doubled and today stand above that of their large bank peers. Notably, Forum member capital ratios actually increased during the pandemic experience of the last few years. This point was also underscored recently by Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell when he said that “we increased capital and liquidity requirements for the largest banks—and currently, capital and liquidity levels at our largest, most systemically important banks are at multidecade highs.”

Accordingly, there is simply no question that Forum members are robustly capitalized. Additionally, and importantly, large bank capital requirements for Forum members are significantly more robust than those of their foreign counterparts primarily because U.S. GSIBs (Forum members) are subject to a more stringent GSIB surcharge and a stress capital buffer that is not applied internationally. Consequently, relative to both U.S. and foreign counterparts, Forum members maintain substantial amounts of capital to ensure their safety and soundness.

Why are the Basel III Finalization Reforms Necessary? Increased Risk Sensitivity, Not Increased Capital

In 2017, when the BCBS issued the Basel III Finalization package, the rationale for the final reforms was made clear. The Chair of the BCBS indicated that a key motivation for the Basel III Finalization reforms was to “enhance[e] the robustness and risk sensitivity of the standardized approaches for credit risk and operational risk, which will make banks’ capital ratios more comparable.” Thus, these final reforms were issued in an effort to improve the risk-sensitivity and comparability of the large bank capital framework and not to raise overall capital levels. Indeed, the BCBS conducted a rigorous quantitative impact study to gauge the likely impact of the reforms and concluded that “the finalization of Basel III results in no significant increase in overall capital requirements.”

Turning the clock ahead to 2022, there are clear signs that Basel III Finalization may be implemented in a manner that significantly and unnecessarily raises capital requirements across the board for large banks. Recently, the Federal Reserve’s outgoing vice chair for supervision indicated that “implementing the remaining elements of Basel III could result in a material increase in capital levels, perhaps up to 20 percent for our largest holding companies.” Further, a recent study by the European Banking Authority found that implementing the Basel III Finalization reforms would increase European GSIB capital by 23 percent. This development is troubling because it suggests that Basel III Finalization could potentially be implemented in a manner counter to both the original intent and public statements about the quantitative impact of the reforms.

Of course, the disparity between the recent impact studies and the original intentions of the BCBS says nothing about why the estimated impacts have come in so much higher than initially expected. Bank capital is a complex and technical area and changes in the economy or the banking system could be driving these impacts. Regardless, regulators should pay close attention to the estimated impact, assess the drivers, and ensure that any final reforms are in line with the original goal to improve risk-sensitivity and comparability without unnecessarily raising capital levels.

What Does the Pandemic Say About Large Bank Capital? Leading the Way in Resilience and Supporting the Economy

Some outside of the U.S. have suggested that the events of the global pandemic demonstrate a need for further capital reforms. However, the incontrovertible evidence from the U.S. pandemic experience, described above, clearly suggests otherwise. Large U.S. banks entered the pandemic with strong and robust capital levels that have only grown stronger during the course of the pandemic.

In addition, during the pandemic Forum members have provided $9 trillion of lending and financing to households, communities, and businesses small and large to support the economy while strengthening their capital and liquidity positions.

Finally, reforms that significantly and unnecessarily raise capital levels are a cause for concern because capital is not a free resource. As we have discussed in previous posts, continual increases in capital requirements come at a cost to households and businesses who ultimately pay more for fewer financial services, which then puts a drag on the economy. Given the strong and multidecade high levels of capital among the nation’s largest banks, as well as existing requirements that are more stringent than international standards, there is simply no reasonable basis for further increasing capital requirements.

How Should Basel III Finalization be Approached in the U.S.? Recognizing the Unique Features of the U.S. Regulatory System

The Basel III Finalization reforms are international in scope. The motivation for certain elements of these reforms relate directly to features of the non-U.S. regulatory regime. Motivations that may be relevant in non-U.S. contexts should not be uncritically applied to the U.S. context.

One motivation that is often cited for the need to implement Basel III Finalization is the need to “constrain the use of internally modeled approaches” by banks. It must be recognized that this motivation is most relevant for non-U.S. banks as the ability for U.S. banks to use their own internal models (versus standardized regulator models) is severely limited. Specifically, U.S. banks are subject to stringent standardized capital requirements and stress tests that are fully prescribed by regulators and do not rely on bank-supplied inputs.

Another commonly cited motivation for the Basel III Finalization reforms is the need to implement a “risk-sensitive output floor” on risk-weighted assets to ensure that capital requirements remain robust. This motivation also is not relevant in the U.S. context because large U.S. banks are already subject to a statutory floor on capital requirements – the Collins floor – that ensures robust capital levels for U.S. banks. Indeed, the Collins floor has been in effect since the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010 rendering any Basel-based floor unnecessary in the Unites States.

One final motivation for the Basel III Finalization revisions is the need to establish a “finalized leverage ratio.” This motivation is also not relevant in the U.S. context as large banks have been subject to the enhanced supplementary leverage ratio since 2014. More importantly, the events of the pandemic have clearly demonstrated that the leverage ratio is not serving its intended purpose as a backstop to risk-based capital requirements and needs reconsideration. The Federal Reserve has indicated that it plans to seek comment on adjustments to the leverage ratio as a direct outgrowth of the pandemic experience. Accordingly, not only is the establishment of a “finalized leverage ratio” not necessary in the United States, but the leverage ratio we do have must be revisited.

Conclusion

Forum members support robust capital requirements to ensure a safe and sound banking system. Forum member capital levels are robust, at multidecade highs, and have only increased despite the enormous headwinds from the pandemic. Improving the risk-sensitivity of the large bank capital framework is a sensible goal, but reforms that primarily raise capital levels are unnecessary and inconsistent with the stated intent of the reforms. Importantly, Forum members are already subject to capital standards that go well-beyond international standards. Relatedly, some motivations for the Basel III Finalization reforms that are relevant outside the U.S. are not relevant in the U.S. Ultimately, as regulators move ahead with these reforms, there should be due consideration of how any such reforms align with their stated intent, how they fit within the U.S. regulatory context, and how they impact the U.S. economy.