Introduction

All good Superman fans are familiar with Bizarro world – a land in which up is down and everything is backwards. In Bizarro world, Superman is a villain and everything is the opposite of what it should be. Without a doubt, the events of the past two years have thrust all of us into situations that have a certain “bizarro” element to them in one way or another – how else would you describe working from home in your pajamas? In the bank regulatory sphere, the case of the GSIB surcharge presents just such a situation that cannot go unexamined. More specifically, over the last few years, the score upon which the GSIB surcharge is based has drifted further and further away from economic reality and now presents a particularly distorted view of systemic risk that should be addressed by regulators. In this post, we review the recent trend in the GSIB score and demonstrate how its growth actually signals reduced systemic risk. Paradoxically, if left unabated, the GSIB surcharge will demand ever higher amounts of required capital from large banks that have actually reduced their level of systemic risk over the past few years. Accordingly, regulators should act promptly to address these shortcomings before they unnecessarily distort capital and lending decisions in the U.S. economy.

The GSIB Surcharge

The Federal Reserve’s GSIB surcharge is an additional capital surcharge that is applied to U.S. Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIBs) – all of which are Financial Services Forum members. The level of the capital surcharge depends on a regulator-defined measure of systemic risk – the GSIB score. A higher GSIB score, according to regulators, equates to a higher level of systemic risk and a higher GSIB surcharge. The GSIB score itself depends on a number of complex metrics, but the score metrics can be classified into the following five broad categories depicted in Table 1. In the table we also provide a brief characterization of regulators’ rationale underpinning each category’s inclusion in the GSIB score as a measure of “systemic risk.”

|

Table 1: GSIB Score Components and Regulator Rationale |

|

| GSIB Score Category | Rationale for Inclusion in GSIB Score |

| Size | The failure of a large bank causes more damage to the economy than that of a small bank |

| Interconnectedness | A bank that is more connected to other entities may cause more damage to the economy if it fails as its failure will have greater “knock-on” effects |

| Complexity | A bank that is more complex is more likely to be subject to complex risks that are systemically risky |

| Cross-Jurisdictional Activity | A bank that has more activity across countries is more likely to present systemic risks internationally |

| Short-Term Wholesale Funding (STWF) | A bank that funds itself with more short-term debt is more likely to experience a destabilizing bank run |

To be clear, the arguments in favor of these score components are not always clear and are often debatable. As an example, the interconnectedness category focuses on the prospect for a bank with many connections to inflict damage on its counterparties, but, at the same time, ignores the fact that those very connections improve overall diversification and make the bank less susceptible to the stress or failure of any single counterparty. Regardless, the GSIB score is what it is and now we move onto recent trends in the score and how those trends demonstrate a decline rather than an increase in systemic risk.

Recent Trends in the GSIB Score

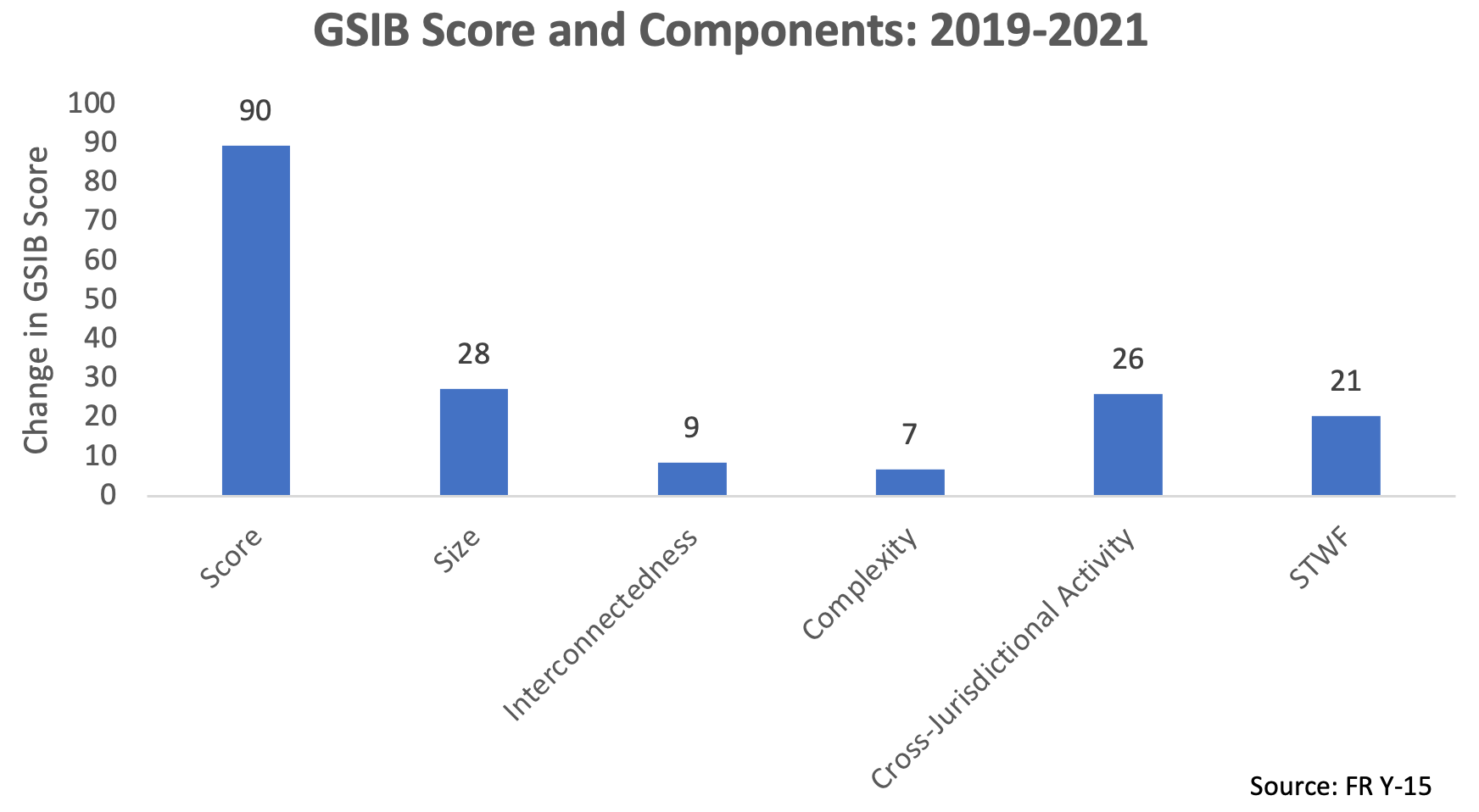

The chart below shows the overall increase in the weighted average GSIB score of Forum members over the past two years – from Q4 of 2019 through Q4 of 2021. This time period is worthy of focused consideration because it coincides with the pandemic period that has seen so many public health and economic challenges that have been met with an unprecedented government response.

response.

As shown in the chart, the weighted average GSIB score has increased by 90 score points, which equates to a 17 percent increase, in the past two years. This increase is material and would be expected to result in increases to GSIB surcharges for several Forum members. As a result, it is important to ask whether these potential increases make sense and whether they relate to an actual increase in systemic risk? In what follows, we briefly discuss the economics behind two of the larger drivers of the increasing GSIB score: Size and STWF.

Increased Size Does Not Reflect Increased Systemic Risk

Over the past two years, the entire banking system has witnessed an overall increase in the level of bank assets as a direct result of the Federal Reserve’s unprecedented monetary policy. Since the onset of the pandemic, the Federal Reserve has increased its balance sheet from roughly $4.2 trillion to $8.8 trillion. The Federal Reserve increases the size of its balance sheet by expanding the amount of bank reserves held by commercial banks. Moreover, the Fed unilaterally controls the level of bank reserves in the financial system. Accordingly, there is no way for the banking system to shed this extremely large build-up of reserves unless the Federal Reserve decides to reduce the size of its balance sheet.

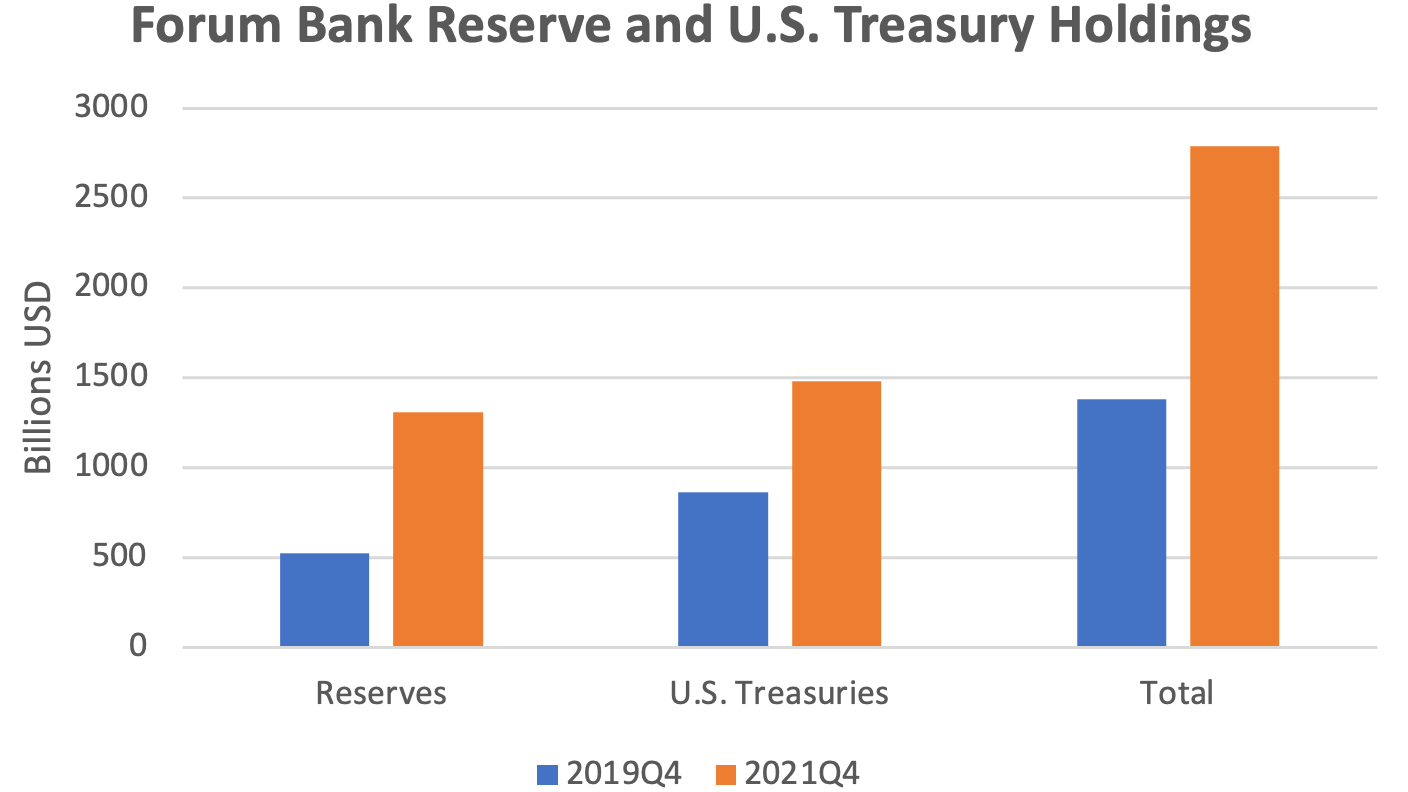

The use of the size factor as a measure of systemic risk does not make sense when the size of the entire banking system’s assets is being increased by the government – especially when the increase is so sharp and concentrated over such a short period of time. Moreover, during this period large bank balance sheets have become, if anything, less risky as large banks have substantially increased their holdings of bank reserves and U.S. Treasury securities – which pose little or no risk. The chart below shows the overall increase in Forum members’ holdings of bank reserves and

As shown in the chart, Forum member holdings of bank reserves and U.S Treasury securities have increased by over $1.4 trillion. This represents a massive dollar increase as well as an increase in the proportion of Forum assets held as bank reserves and U.S. Treasury securities. It is difficult to fathom how the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet policy that has resulted in substantially larger holdings of zero risk bank reserves and low-risk Treasury securities could possibly represent an increase in systemic risk. If anything, these developments have lowered systemic risks as the Federal Reserve’s policies have reduced macroeconomic risks and large banks have reduced their risks by increasing their holdings of low-risk assets.

Increased STWF Does Not Reflect Increased Systemic Risk

As shown previously, the magnitude of the short-term wholesale funding component of the GSIB surcharge (STWF) has increased markedly over the past two years. At first glance, such an increase might appear to signal an increase in systemic risks. But to truly assess systemic risks, we have to “look under the hood” of the STWF indicator and ask what exactly is driving the increase. Thankfully, researchers at the Federal Reserve and the University of Chicago have recently conducted this exercise.

These researchers find that, increasingly, large banks take large deposits from large financial institutions and invest them in zero risk reserves at the Federal Reserve. This is perhaps the safest and least systemically risky of all bank assets. For technical reasons, these transactions are identified as “short-term wholesale funding,” but these transactions have nothing to do with transactions in which short-term borrowings are used to fund risky assets. Rather, the opposite is true. If, for any reason, a large financial institution demanded its large deposit be returned, the bank in question would simply transfer the reserves held at the Federal Reserve to the entity seeking funds. No assets would need to be sold and there would be no delay in providing the needed funds. Accordingly, the traditional “fire-sale” dynamics that motivate the use of STWF as a systemic risk indicator are completely absent in this context.

Rather than raise systemic risk, these transactions are actually more likely to lower systemic risk. As noted by the authors of the research paper, “global banks have become more resilient to negative wholesale funding shocks, as they can swiftly reduce their arbitrage positions in response to wholesale funding dry-ups.” In this important sense, the entire nature of STWF has changed in an environment in which more and more large financial institutions are relying on large banks to safely hold their deposits in the form of zero risk, liquid reserves at the Federal Reserve.

Conclusion

The past few years have tested all of our assumptions about how the world works. Our basic sense of up and down have quite understandably been challenged as we have all worked to steady ourselves in the topsy-turvy world of the past few years. As we continue to emerge from the ongoing challenges of the pandemic, regulators should turn to recent and anomalous developments in GSIB scores. Developments reflecting a clear decline in systemic risk should not inappropriately translate into higher capital requirements that will only serve to unnecessarily increase costs to businesses, consumers, and the economy.