Introduction

A key priority of regulators in the U.S. and Europe is the implementation of the Basel III Finalization (B3F) framework, which makes a variety of adjustments to the original Basel III package that was adopted a decade ago. Recently, Europe has issued a proposal on how Basel III Finalization would be implemented in Europe and U.S. regulators are expected to issue their own proposal in the near future. The Basel III Finalization framework – as agreed to internationally — has important implications for certain smaller, private companies that rely on bank lending to finance their investments and do not finance their investment by issuing publicly traded debt and equity securities. Under the framework, U.S. banks lending to these smaller, private companies would be subject to higher capital requirements than larger corporations that issue publicly traded securities. This is problematic because overall creditworthiness is not fundamentally related to whether a company issues securities and firms that do not issue securities to finance their investment are fundamentally more reliant on bank financing. As a result, this new capital rule could unnecessarily limit bank credit for precisely those creditworthy companies that are in the greatest need of bank financing. In this post, we describe the issue, dimension the size of the problem, and discuss important features of the recent European proposal, which suggest a potential approach for ensuring that credit is not unnecessarily restricted from creditworthy companies in the United States.

Bank Credit to Corporate Borrowers: The Current Regime

In the United States, banks that make corporate loans are required to apply a risk weight of 100 percent under standardized capital rules. This means that if a bank has a capital requirement of, say, 12 percent, then the bank must maintain an additional $12 for every $100 in lending that it provides to a corporate borrower regardless of its creditworthiness. Accordingly, a company that has been in operation for 10 years and has borrowed and paid back several bank loans is treated identically to a new, start-up company that has little experience and has never taken out and repaid a bank loan. This approach to capitalizing bank lending to corporates is problematic because it lacks any risk sensitivity – a bank should not need to maintain as much capital to support a loan to a highly creditworthy corporate borrower as it does to a newer and less creditworthy borrower. Ultimately, the lack in risk sensitivity means that more creditworthy borrowers pay higher loan rates and receive less credit than they should based on fundamental credit risk. In Europe, banks are permitted to recognize more creditworthy borrowers through the use of public credit ratings, but that approach is prohibited in the United States due to a provision of the Dodd-Frank Act that prohibits the use of credit ratings in U.S. bank regulation.

Brighter Days Ahead for Corporate Borrowers?

The lack of risk sensitivity in capital requirements for corporate lending is well known by regulators. In the past few years, regulators have attempted to address this problem. More specifically, the Basel III Finalization framework allows banks to identify sufficiently creditworthy borrowers as “investment grade.” A borrower that is investment grade should, according to the bank’s credit analysis, have the financial wherewithal to repay a loan and make all required interest payments with a high degree of certainty. These investment grade – or IG – borrowers would then be subject to a 65 percent risk weight. As a result, if a bank is required to maintain 12 percent capital on a loan to a riskier start up, then a loan to a safer IG borrower would only require roughly 8 percent capital. The resulting lower capital requirement would then allow the bank to extend credit to the IG borrower at a lower and more affordable interest rate.

Unfortunately, the story does not end here. The same B3F proposal only allows a bank to identify a corporate borrower as IG if the borrower issues securities, such as equity, that are publicly traded. This provision of the proposal is highly problematic because a large number of creditworthy companies that borrow from banks do not issue publicly traded securities. Additionally, over the past twenty years, there has been a growing trend for firms to remain private and not issue public securities for a variety of reasons related to maintaining corporate control and the regulatory burdens associated with going public. Accordingly, a very large number of creditworthy borrowers would be restricted from this risk-sensitive capital treatment, which undercuts the entire motivation for establishing the IG designation in the first place.

How Problematic is the Public Securities Requirement?

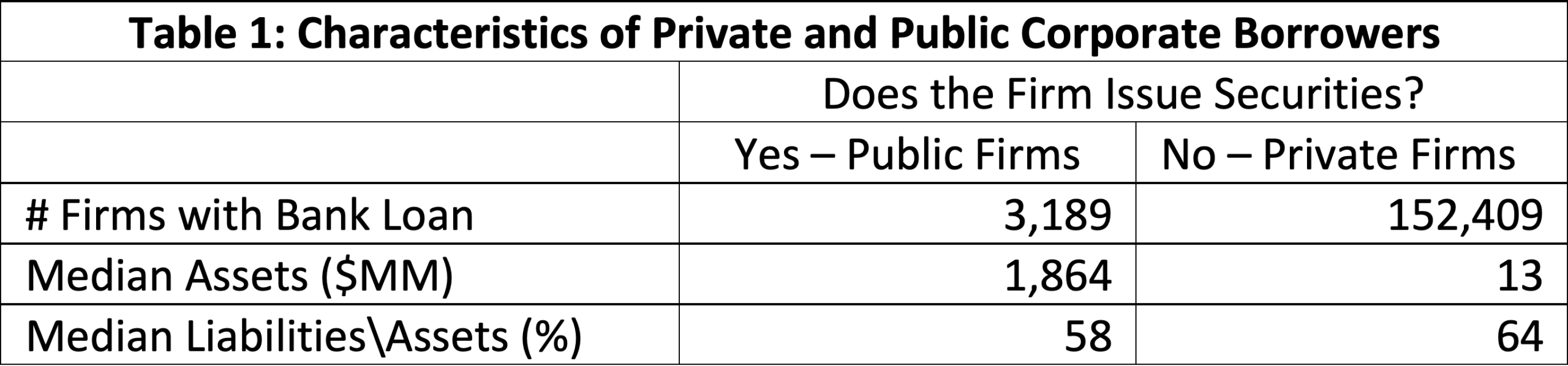

Recent research from the Federal Reserve Board and the University of Maryland can be used to assess the costs associated with requiring corporate borrowers to be issuers of publicly traded securities in order to be considered IG. Specifically, these researchers use confidential regulatory data from 39 large U.S. banks to measure the number and type of firms that benefit from bank lending. The researchers also identify which firms are issuers of publicly traded securities and which aren’t. Table 1 below shows some select data characteristics from their research.

The first row of Table 1 shows that there are over 150,000 private firms that borrow from large banks while there are only roughly 3,200 public firms that borrow from banks. Accordingly, the requirements that a firm be an issuer of publicly traded securities would make it impossible for over 150,000 companies to be considered investment grade regardless of their credit quality or borrowing experience. The data in Table 1 also show that private firms are generally much smaller than public firms with a median asset value of only $13 million versus $1.9 billion for public firms. As a result, restricting the IG designation to public firms would disadvantage smaller businesses. Finally, the last row of Table 1 shows the fraction of firm assets financed with liabilities such as bank debt. Private firms generally carry slightly more debt than public firms – in large part because public firms are able to tap public equity markets. In this sense, limiting the IG designation is especially problematic because it disadvantages those firms that are more dependent on borrowing, and bank borrowing in particular, to finance their investment and growth.

It may not be the case that all 152,409 private firms identified in Table 1 would meet the investment grade standard. At the same time, if even a modest fraction of private firms are fundamentally creditworthy, then limiting the IG designation solely to public firms would unnecessarily limit credit to thousands of deserving companies that are important to supporting the U.S. economy.

Looking to the Europeans for a Path Forward

Recently, Europe took a step toward codifying the Basel III Finalization framework into a national rule. As discussed above, in Europe banks are allowed to use credit ratings to effectively determine which corporate borrowers are creditworthy and subject to a less-than 100 percent risk weight. Under the B3F framework, a company without a credit rating would also not be eligible for this more risk-sensitive treatment, which is itself problematic and similar to the requirement for a company to issue publicly traded securities.

The recent European proposal, however, recognizes the problematic restriction to companies with a credit rating and the impact it would have on smaller, unrated companies in need of bank credit. In response, the European proposal sets up a multi-year transitional arrangement that allows unrated corporates that are sufficiently creditworthy to be eligible for an investment grade rating and a 65 percent risk weight. The transitional arrangement clearly states that to be eligible for the 65 percent risk weight there is no requirement that the company either have a credit rating or issue publicly traded securities. Further, the proposal empowers the European Banking Authority to monitor the use of the transitional arrangement and inform the European Parliament on its use so that it can consider a legislative proposal to deal with the treatment of unrated corporate borrowers.

The approach taken in the European proposal is sensible and clearly recognizes the negative consequences of unnecessarily restricting credit from creditworthy borrowers for reasons unrelated to their credit risk. As the U.S. moves forward with its proposal, regulators should consider the European proposal and how to ensure that bank credit is not unnecessarily restricted for creditworthy corporate borrowers.

Conclusion

The ability of creditworthy companies to obtain bank credit is important for the growth of the U.S. economy. The current B3F proposal to recognize more creditworthy borrowers would limit the application to only those companies that issue publicly traded securities. Data from the Federal Reserve show that this would restrict over 150,000 companies from being considered investment grade, limiting their ability to access bank credit at reasonable cost. More importantly, this restriction would impact those companies that are generally smaller, and rely more heavily on bank credit. Recently, the Europeans have put forward a proposal that addresses this problem. U.S. regulators should consider the European proposal as they move forward to ensure that credit is not unnecessarily restricted for creditworthy companies that contribute so much to the U.S. economy.