Introduction

In a recent Brookings paper, former Federal Reserve Governor Daniel Tarullo claims that the stress tests have become less “dynamic.” In this post we investigate this claim by analyzing both the inputs and the outputs of the stress testing process. Our data analysis does not support the claim that the stress testing process has become less dynamic in recent years. Relatedly, we address the oft quoted claim that the move to embed the stress tests into the capital regime through the stress capital buffer (SCB) rule reduced capital requirements for Forum members. Quite to the contrary, the Federal Reserve’s own analysis clearly demonstrates that changes made to the stress testing regime as part of the stress capital buffer rulemaking increased required capital for Forum members.

“Dynamism” in the Stress Tests

Daniel Tarullo’s paper opens by claiming that “over time, these factors have made the stress testing regime, and thus the capital requirements coming out of the CCAR and SCB processes, less dynamic and more predictable – that is something closer to a variation on point-in-time capital requirements.”

The paper offers little in the way of direct, data-based evidence to support the claim and that may simply be because it’s not entirely clear what it means for the stress tests to be less “dynamic” and more “predictable.” For example, is the concern that the stress tests take place at regular intervals or rely on a consistent set of data, models, and processes to produce the results? Is it because the stress testing process has been formally included as part of rule-based and transparent capital regulation? All of those aspects of the stress testing regime are indeed “routine” and “predictable,” but they are also the hallmark of good, transparent government regulation that is regularly practiced across an array of regulatory contexts whether it be the regulation of banks, airlines, or automakers.

To further assess the claim, we have reviewed publicly available data on the annual stress tests between 2011-2023. We assess the dynamism of the stress tests in two specific, and data-based ways. One approach considers the key inputs to the stress tests while the other considers the outputs of the stress testing process.

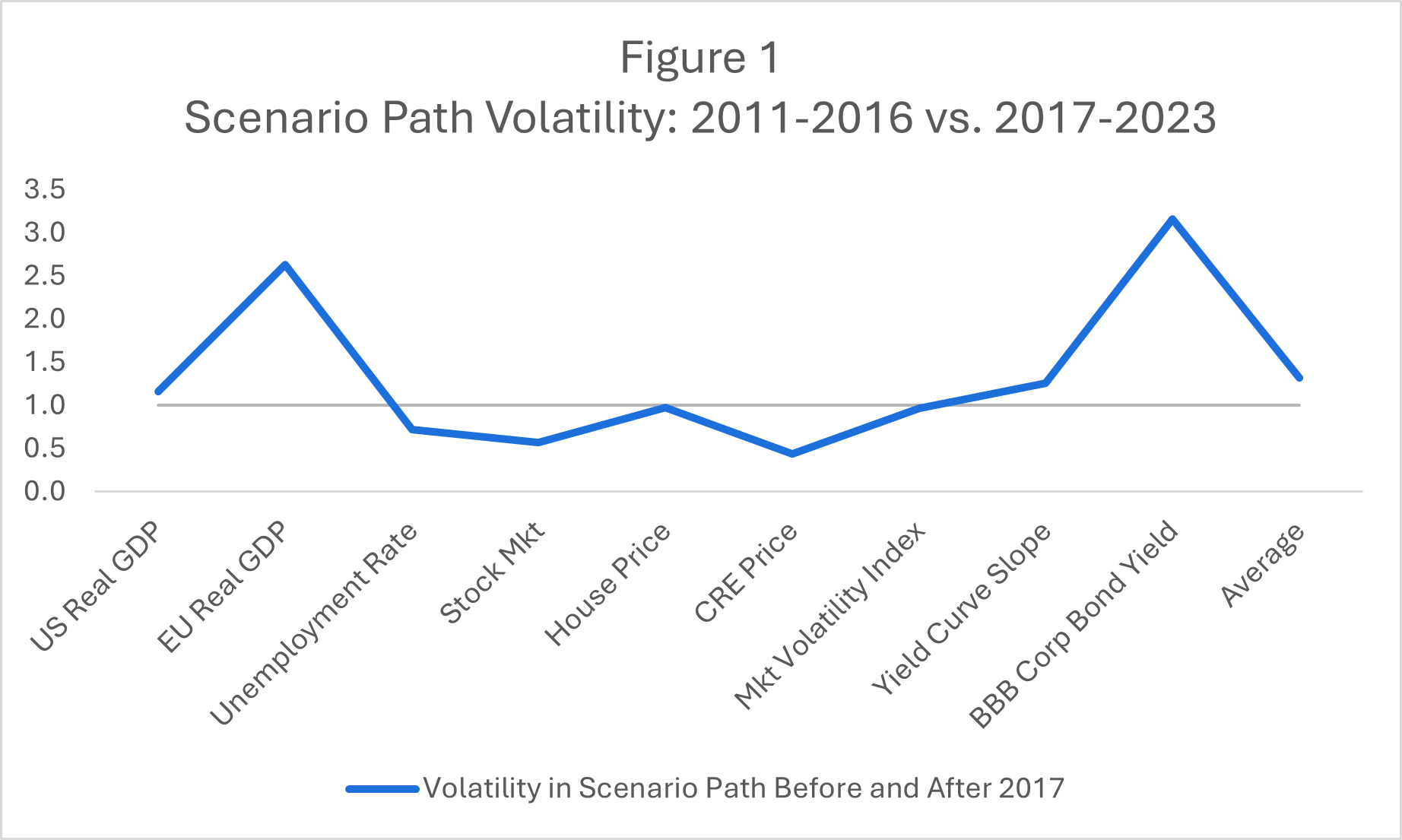

On the input side, we consider the variability in key stress test scenario variables: US Real GDP, EU Real GDP, Unemployment Rate, Stock Prices, House Prices, CRE Prices, Stock Market Volatility, Yield Curve Slope, and BBB Corporate Bond Yields. These are the key macroeconomic scenario variables that are inputs to the stress tests and are under the direct control of the Federal Reserve Board. A less dynamic stress test would be one in which the variability in these key variables declined substantially over time. As an example, if the Federal Reserve stated that the stock market declined (peak to trough) by 50 percent in each stress test, then that would certainly be less dynamic and more predictable. Banks would understand that in the upcoming year’s stress test the scenario will feature a 50 percent stock market decline. Alternatively, a situation in which the scenario’s stock market decline varied consistently from one year to the next – a decline of 40 percent in one year, 50 percent in another and 35 percent in yet another would demonstrate a consistent and healthy amount of dynamism in the stress test’s key inputs. We assess this measure of dynamism by comparing the standard deviation in the peak to trough scenario path for each of the aforementioned scenario variables over two periods: 2011-2016 and 2017-2023. A finding that the volatility of scenario paths had declined significantly in the later period would signal a decline in dynamism.

In Figure 1, we present the ratio of the volatility of scenario paths for each key stress test variable over the 2011-2016 and 2017-2023 time periods. A value of 1.0 means that the scenario path was just as volatile in the 2011-2016 period as it was during the 2017-2023 period. A value larger (smaller) than 1.0 means that the scenario path became more (less) volatile over the 2017-2023 period relative to the 2011-2016 period. As shown in the Figure, stress scenario volatility is somewhat mixed. Some variables, such as EU Real GDP and BBB Corporate Bond Yields are significantly more volatile in the later period than the earlier period while other variables such as CRE Prices, Stock Prices, and the Unemployment Rate are somewhat less volatile in the later period. Averaging across all variables shows that stress scenario variables are more volatile (1.36) now than they were in the past. Accordingly, a case can be made that the Federal Reserve’s stress scenario process has indeed become more dynamic in recent times.

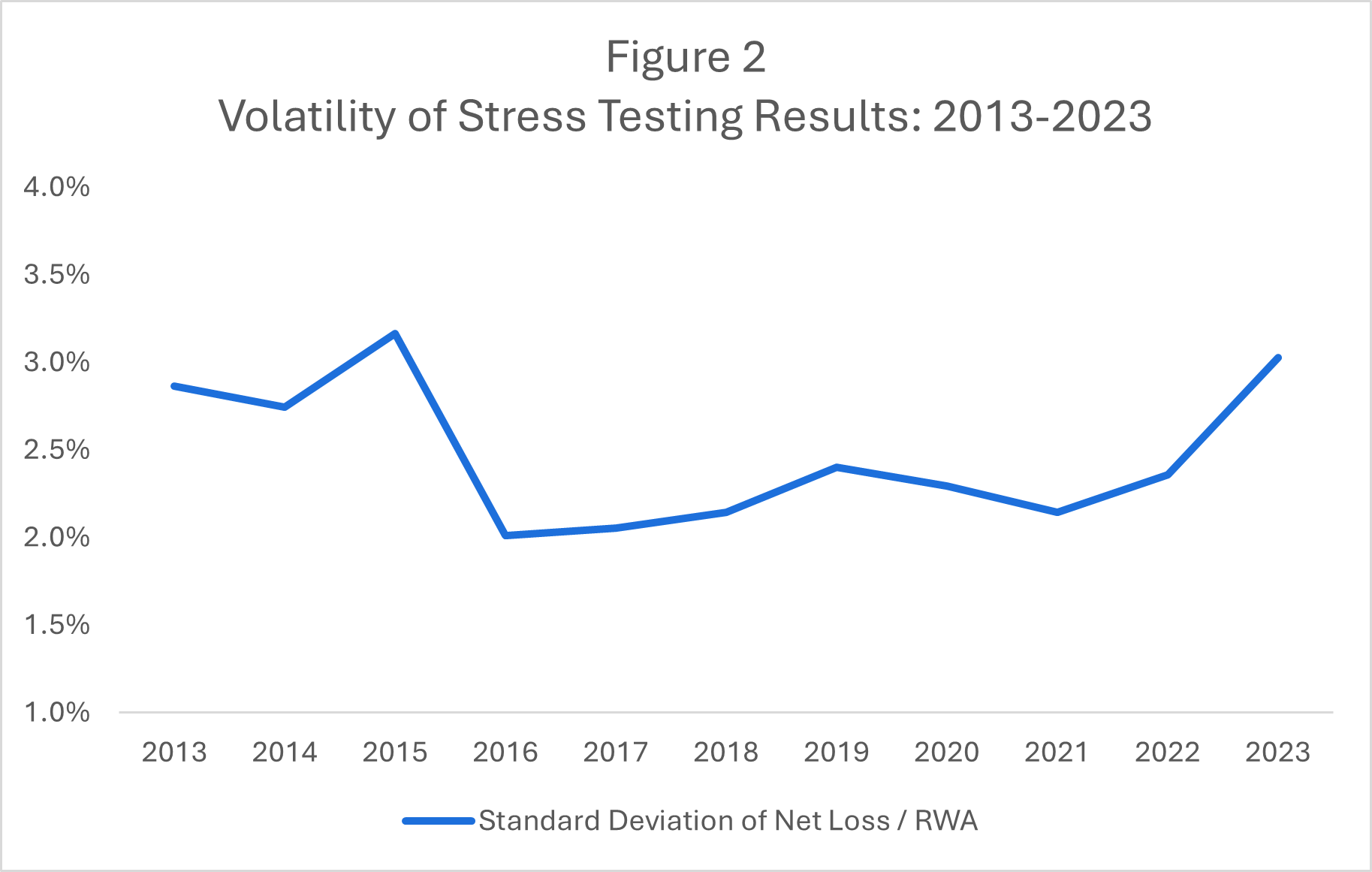

On the output side, we consider the variability in the results of the stress tests. The easiest way to assess output variability would be to compare the variability in stress capital buffers (SCBs) from one year to the next. Given the SCB was first implemented in 2020, we only have a small time series of SCBs so we consider a useful proxy – the ratio of each bank’s stress test losses (losses net of income) to its risk weighted assets. As before, a stress testing regime in which all banks are converging to a constant loss ratio (SCB) – say 4 percent – from one year to the next would signal reduced dynamism while a regime that shows significant variation from one year to the next, 4 percent in one year, 3 percent in another and then 4.5 percent would indicate a healthy degree of dynamism.

In Figure 2, we present the volatility in our SCB proxy (net stress test loss/RWA) for each year from 2013-2023. As shown in the chart, the volatility of stress test results hovers around two to three percent from 2013-2023 with no clear and significant pattern either up or down over time. Notably, the volatility is as high in 2023 as it was in 2013. Also, the average stress test loss relative to RWA tends to be about one percent, so a volatility of two to three percent is quite significant. Of course, one may claim that the volatility in stress test losses is simply a product of variation in the population of banks subject to the test – some banks have decidedly different risk profiles and business models than other banks and that results in different stress loss results. That is undoubtedly true, but a more fine-grained analysis of stress losses that controls for bank characteristics would be a significantly more complicated and opaque undertaking that would invite other questions. A perusal of actual SCB results over the past few years supports the finding of this analysis. Just looking at the difference between the 2022 and 2023 results shows that changes of 50 to 100 basis points in a bank’s SCB are not uncommon. Against this backdrop, it is puzzling to understand exactly what data, analysis or evidence underpins the claim that the stress tests are becoming less “dynamic.”

Changes to the Stress Tests Have Raised Capital Requirements for Forum Members

Another claim referenced in the paper is the view that changes to the stress tests that occurred in connection with the implementation of the SCB rulemaking have reduced capital requirements for Forum members. This claim is demonstrably false. Indeed, the Federal Reserve’s own analysis regarding the impact of the rule on the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) for Forum members clearly stated that “for GSIBs, the largest and most systemically important firms, the draft final rule would lead to an aggregate increase in CET1 capital requirements of approximately $46 billion, on average, a seven percent increase in their current aggregate CET1 capital requirement.”

The above point is exceedingly simple and clear. Forum members face higher capital requirements today because of the SCB final rule than they would have faced had the SCB rule not been adopted. Period. End of story. There is no sense in which the SCB rule reduced capital requirements for Forum members. The opposite is true. Of course, some may have hoped that the SCB rule would have increased Forum capital requirements by an even larger amount but that is a different matter altogether.

Conclusion

The Federal Reserve’s stress testing is far from perfect and could benefit from a number of changes to improve its risk sensitivity and transparency. A lack of dynamism, however, is not a problem for the stress testing regime. In this post we analyzed publicly available data on the stress tests from 2011-2023 to quantitatively analyze the claim that the stress tests have become less dynamic over time. Analyzing both the inputs and outputs of the stress tests between 2011-2023 shows no diminution in dynamism over time. Relatedly, the stress tests have also not resulted in lower capital requirements for Forum members. Rather, and quite to the contrary, Forum members’ capital requirements increased as a result of the change to the stress tests that occurred with the implementation of the Federal Reserve’s Stress Capital Buffer rule.