Introduction

Since the onset of the pandemic, the U.S. government has increased the level of outstanding Treasury debt by roughly one-third, or $7 trillion. This rapid and significant increase in the supply of Treasury debt demands a commensurately more robust and well-functioning secondary market for U.S. Treasury securities to ensure that the U.S. government can manage the increased cost of financing the pandemic response. Large bank securities dealers play an essential role in the Treasury market by holding Treasury securities and providing much needed liquidity in the secondary market. At the same time, however, a risk-insensitive capital requirement – the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) – has increasingly limited the ability of these banks to perform this role. In this post, we review some of the facts regarding the U.S. Treasury market, its interaction with the supplementary leverage ratio, and broader implications of a binding SLR for markets and the economy.

U.S. Treasury Markets and Bank Capital: Then and Now

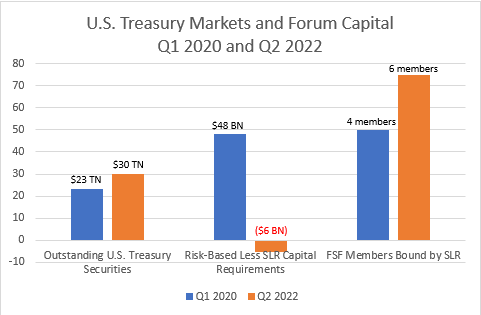

The chart below shows for the first quarter of 2020 and the second quarter of 2022, 1) the amount of outstanding U.S. Treasury securities, 2) the difference between aggregate risk-based capital requirements and the risk-blind capital requirements of the SLR for the eight Financial Services Forum members, and 3) the number of Forum members for which the SLR is the binding capital constraint. Under U.S. bank capital rules, risk-based capital requirements serve as a primary tool to ensure that institutions are adequately capitalized for the relative risk of assets held. Leverage capital – which is calculated the same way regardless of the riskiness of assets – is intended to serve as a backstop. Whenever a Forum member has an SLR capital requirement that exceeds its risk-based requirement, the SLR is no longer a backstop, but the binding capital constraint on the bank’s lending, underwriting, and market making activities.

As shown in the first set of bars, the amount of outstanding U.S. Treasury debt has increased substantially over the past few years, in large part to fund the government’s extensive response to the pandemic. At the same time, there has been increasing evidence that the functioning of U.S. Treasury markets has been worsening. Recent reports point to increasing volatility and rising transaction costs in the U.S. Treasury market. Such reports of a deterioration in Treasury market functioning have become increasingly common since the onset of the pandemic and were raised by several former regulators as a cause for concern during the Forum’s summit on July 18.

A robust market for U.S. Treasury securities is of paramount importance to ensure that the U.S. government can continue to attract capital at reasonable cost to the U.S. taxpayer. In addition, some macro trends in the economy suggest that U.S. Treasury markets are likely to face more and not fewer headwinds in the future. More specifically, the Federal Reserve has already announced that it will be reducing its own holdings of U.S. Treasury securities, thereby increasing the need for secondary market intermediation to absorb the increase in market supply. In addition, foreign investors appear, at least presently, to be less willing to hold U.S. Treasuries. According to data from the Federal Reserve from the first quarter of 2020, 33 percent of U.S. Treasuries were held outside the U.S. As of the first quarter of 2022, only 30 percent of U.S. Treasuries were held internationally. With more sellers and fewer buyers, the demands on market makers in the Treasury market will be heightened for the foreseeable future.

Bank Capital and Treasury Markets

Forum members and other large banks comprise the vast bulk of market making capacity in the U.S. Treasury market. Accordingly, capital constraints that disincentivize market making for large banks have a direct impact on the functioning of the entire U.S. Treasury market.

As shown in the figure, back in 2020, risk-based capital requirements for Forum members were, in the aggregate, $48 billion higher than capital requirements as prescribed by the SLR. Under risk-based capital rules, U.S. Treasury securities held in the banking book have a zero-risk weight meaning that no additional capital is required to support the holding of a Treasury security. Treasury securities that are held explicitly for trading are subject to more complex trading book capital rules, but the resulting risk weight is relatively low owing to the fact that Treasury securities have no default risk and generally low price volatility. Under the SLR, however, a $100 Treasury security must be supported by $5 in capital. When SLR-based capital requirements are higher than the risk-based requirements, the SLR requirements become the “binding constraint” and banks must effectively maintain $5 in capital for every $100 in Treasury securities. Accordingly, a situation in which risk-based requirements are comfortably higher than SLR requirements is more conducive to supporting secondary market trading of Treasury securities. Finally, it should be noted that while aggregate risk-based requirements were higher than SLR requirements in 2020, it was still the case that four of the Forum’s eight members had SLR requirements that were higher than their risk-based requirements, thereby putting some pressure on their dealing activities.

Fast forward to 2022 and the situation is demonstrably worse for the Treasury market. As of the second quarter of 2022, Forum members, in aggregate, have SLR capital requirements that are $6 billion higher than their risk-based requirements. Now, six of the Forum’s eight members are bound by SLR requirements rather than risk-based requirements. As a result, at a time during which the need is acute for more robust and better functioning Treasury markets, risk-insensitive capital requirements have worsened the challenges faced by dealers seeking to provide liquidity and continuity in this critical financial market.

An Old Problem with a Straightforward Solution

The concerns around the binding nature of the SLR are not new. Back in 2020, the Federal Reserve temporarily modified the SLR for the expressed purpose of “easing strains in the Treasury market.” Later, when the Federal Reserve let the temporary changes to the SLR lapse in March 2021, it committed that it would “soon be inviting public comment on several potential SLR modifications.” In the 15 months that have passed, no proposals have been released, the SLR has continued to become more binding, and underlying conditions in the Treasury market have deteriorated.

Deteriorating Treasury markets and increasingly binding SLR requirements have not gone unnoticed. Recently, the Group of 30 – a group of global policymakers, including the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and the Secretary of the Treasury (as an advisory member) – issued a status update on the U.S. Treasury market. The report squarely addresses the SLR and finds that:

[A]s Treasury debt continues to grow rapidly and market-making capacity remains limited and concentrated, the Treasury market almost surely remains highly susceptible to dysfunction under stress, and potential sources of stress are forbidding.

while also noting that,

“[t]he liquidity of the Treasury market under stress is reliant on a small number of very large broker-dealer affiliates of U.S. global systemically important banks (U.S. GSIBs). In large measure because of the massive expansion in recent years of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet (and the accompanying expansion of central bank balances on bank balance sheets), risk-insensitive leverage ratios (notably, the Supplemental Leverage Ratio [SLR]) have become the binding regulatory constraint on the allocation of capital for most of the banks whose dealer subsidiaries are the largest providers of liquidity to the Treasury markets.”

In addition, the report makes a clear recommendation about how to alleviate the problem created by the SLR. Specifically, the report recommends that “banking regulators should adjust leverage and risk-based capital requirements to ensure that leverage requirements are backstops to risk-based requirements rather than binding constraints on bank behavior.”

Shell Games and Broader Implications of Capital Reform

The need to recalibrate the SLR is widely recognized and long overdue. Moreover, while there has been appropriate focus on Treasury markets, we should not lose sight of the basic fact that risk-insensitive capital requirements are problematic for assets and markets well beyond the Treasury market. The holding and intermediation of any asset is negatively impacted by capital requirements that do not account for risk – corporate lending, the intermediation of municipal debt, and a host of other activities are inappropriately disincentivized by risk-insensitive capital requirements. In a complex world, painting every activity with the same brush, by its nature, cannot lead to an efficient or effective outcome.

Finally, some have suggested that that one way of “solving” the problem with the SLR would be to arbitrarily raise risk-based requirements to offset any reduction in capital that might occur in recalibrating the SLR. Any such reverse engineering of risk-based requirements would be misguided and would represent a classic case of the “cure being worse than the disease.” Risk-based capital requirements should be just that – based on underlying risk and fundamentals. Currently, regulators are in the process of reforming the existing risk-based framework as part of the Basel III Finalization process. Accordingly, regulators have every opportunity to assess the adequacy and effectiveness of risk-based requirements. Simply re-labeling leverage capital as risk-based capital for the narrow purpose of maintaining an arbitrary level of capital in the banking system would undercut the entire purpose of the risk-based system and result in raising the cost of all credit products while easing the cost of financing the U.S. government.

Conclusion

A smooth running and robust market for U.S. Treasury securities is important for the U.S. government, the U.S. economy, and the world economy. The SLR is now binding on large banks and the U.S. Treasury market is being adversely impacted at a time when it can least afford it. Over 15 months ago, the Federal Reserve pledged to seek public comment on ways to deal with the unnecessarily binding nature of the SLR. The time has come to move forward on SLR reform to ensure it plays a role as a backstop without unnecessarily restricting credit to any sector of the economy. SLR reform should come quickly and should not be done in a way that makes the current problem permanent in the guise of “modified” risk-based requirements.