Introduction

Over the last several years there has been a heightened focus on climate-related financial risk in the banking sector. Much of the discussion has been high level and qualitative because of the complex conceptual, data, and modeling challenges at play. Recently, researchers from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and New York University released a research paper that attempts to estimate climate risk in the banking sector. Data-based research that attempts to quantify these risks is welcome because it imposes important and much needed discipline on the problem of quantifying climate related financial risks. At the same time this effort, and efforts like it, should be viewed cautiously in light of its early stages as well as the many significant data, modeling and broader conceptual challenges presented by the problem of measuring climate risk in the financial system. Indeed, a review of the paper’s findings shed important and appropriate light on the high degree of variability and uncertainty in climate risk estimates. Academic research of this kind is in its infancy. Accordingly, the results of this and related research should be viewed with a healthy dose of caution and should not be interpreted as conveying settled or established facts. In this post, we briefly review the paper and discuss some of the conceptual and empirical challenges that are highlighted by this work.

Systemic Risk and Climate Risk: Measurement Challenges

The paper attempts to estimate climate risk by utilizing and further innovating a statistical measure of “systemic risk” – SRISK – that was introduced to the economics literature a decade ago. Ten years sounds like a long time, but in the context of reaching consensus on the` validity of a new empirical measure, 10 years is not very long at all. This is even more true in the case of systemic risk measures because systemic risk is inherently difficult to measure from a conceptual standpoint. These challenges are well known and have been seriously considered for as long as people have been trying to measure systemic risk. And while SRISK is one measure among many that is considered by economists and policymakers, it is far from universally accepted as a measure of systemic risk providing pinpoint accuracy. The climate version of SRISK – CRISK – should accordingly be viewed with an even greater degree of caution and humility. We are still at the early stages of systemic risk measurement and indeed at the earliest stages of systemic climate risk measurement.

Climate Risk Measurement: Conceptual Challenges

The CRISK measure offered by the researchers does present some interesting conceptual questions for climate risk measurement. Put briefly, the CRISK measure attempts to quantify the capital shortfall that would occur at a bank in the event of a significant climate stress event. At a conceptual level, this is an interesting measure, but operationalizing it in practice raises several, important conceptual issues.

First, the measure is heavily dependent on historical fluctuations in the market value of equity. Market values should never be ignored, but market values are also known to be highly susceptible to bouts of volatility that are driven by short-term investor sentiment and not long-run fundamental risks. This feature of asset prices is well known and long ago led Paul Samuelson to famously quip that the stock market had predicted “nine of the last five recessions.” To be clear, market valuations should never be ignored, but there is an open question about how informative they are about long-run, fundamental risks such as systemic climate-related financial risks. Correlations with market values should not be immediately and uncritically identified with fundamental risks like climate risk.

Second, the paper acknowledges that CRISK is solely focused on “transition risk,” by which the authors mean that risk associated with a significant policy shift toward a lower carbon economy, which has negative consequences for certain sectors of the economy. The authors empirically proxy for transition risk by using the market return on a portfolio of fossil fuel companies. The idea is that a policy shift toward a greener economy would result in negative returns to the fossil fuel industry. The analysis then empirically measures the historical sensitivity of bank equity prices to this fossil fuel portfolio.

This exercise is emblematic of much empirical economic research. Researchers have a theoretical concept in mind that they want to measure in the data, but the data are imperfect and some highly imperfect proxy must be put forward to do any analysis. In such cases, we should be careful to consider whether the proxy faithfully and accurately represents the target concept.

In this case, there are reasons to suspect that the identified transition risk proxy may not be fully accurate or adequate. Specifically, the fossil fuel industry could exhibit fluctuations for a number of reasons – such as supply shocks or political instability – that bear no relation to climate risk. Accordingly, the measured sensitivities may reflect sensitivities to factors that are unrelated to climate risk. Moreover, it’s not exactly clear how the fossil fuel industry would adapt – and over what timescale it would adapt – to a green policy transition. For example, fossil fuel industries may innovate and expand into greener technologies that could actually lead to an increase in their equity value. More broadly, the exercise of predicting how transition risk will arise and how it will impact the economy or the banking is sector is speculative by design.

Third, the paper is based on historical statistical analysis. The world learns a lot from historical statistical analysis, but it is important to be fully cognizant of its drawbacks. Predicting the future with the past is fraught with peril and that is especially true when we are considering a transition to a new economic regime that has not been experienced or tested.

CRISK: Some Observations on the Findings

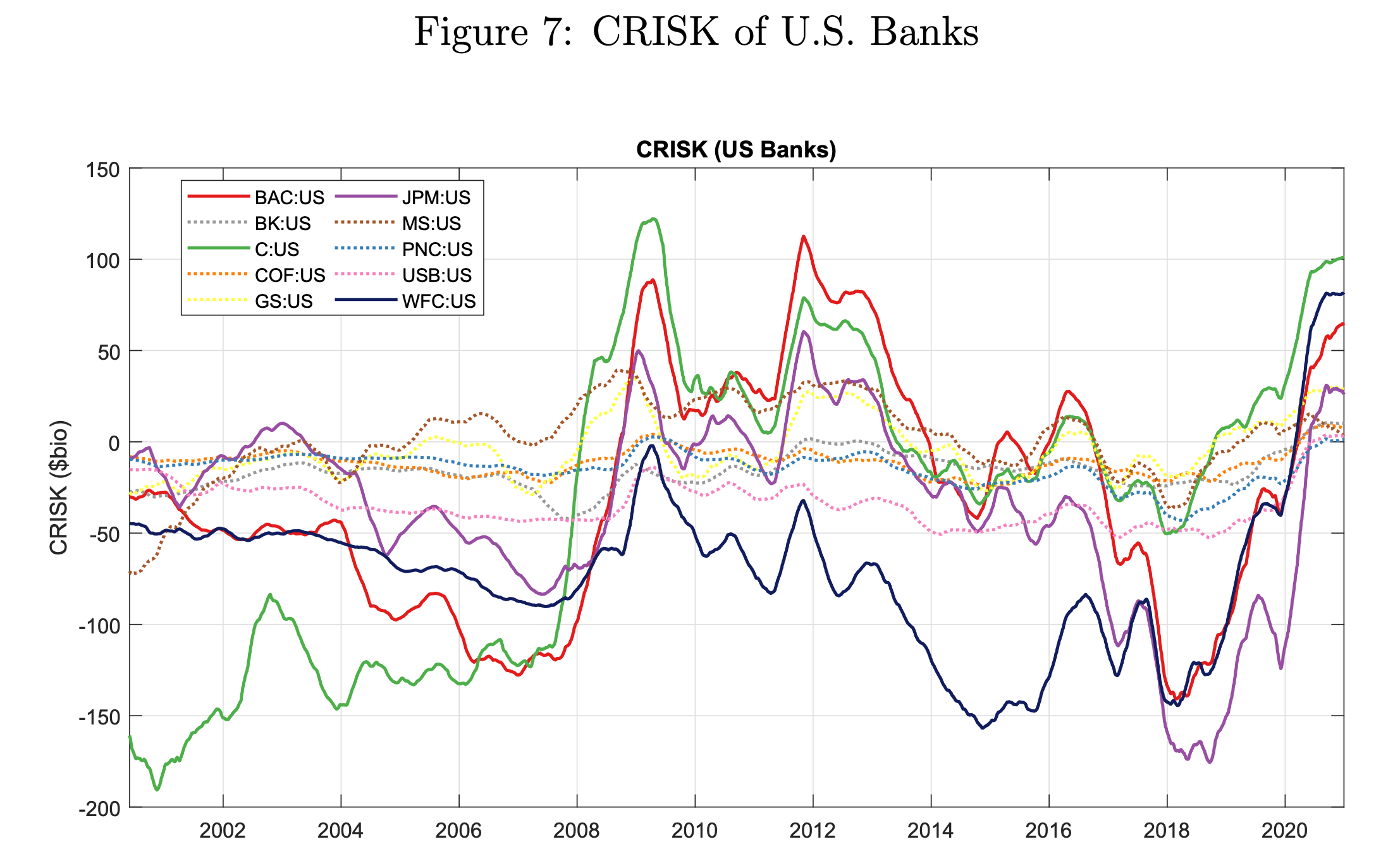

Despite the conceptual and measurement challenges that abound, the research is worthwhile as a means of exploring an interesting question in a systematic fashion. Below, we reproduce the estimated CRISK figure for large U.S. banks and make some observations on the findings.

Recall that the CRISK measure is attempting to measure the capital shortfall that would occur in the event of a systemic, transition-related climate event. Accordingly, a CRISK value of zero implies that a bank has no systemic climate risk, a positive value indicates that a bank would experience a capital shortfall if the systemic climate event is realized, and a negative value implies that a bank would enjoy a capital surplus if the systemic climate event is realized.

The first thing to note from the figure is that the estimates are quite volatile. For some banks the measure ranges from negative to positive $150 billion. Also, these results are “smoothed,” which means that the estimates vary even more in the underlying data and the researchers have averaged the results to suppress the amount of variability in the results. The volatility in the results likely owes to the heavy reliance on financial market values. In reality, it seems doubtful that systemic climate related financial risk varies so much as it should be related to the fundamental risk and business profile of a bank. The variability in these (smoothed) results clearly communicates the noisy and early-stage nature of the climate risk measure.

It is also interesting to note that for all the banks above, the estimated climate risk is often close to zero and more often negative than positive. This means that, according to the analysis, a bank would often experience a rise in its equity value in the event that the hypothetical climate risk event were realized. This finding should also convey the complexity associated with trying to measure systemic climate risks with available data. Some have noted that the estimated level of CRISK for some banks in 2020 is elevated. It is simply not appropriate to evaluate the estimated CRISK measure in 2020 without taking into account the large degree of variability in CRISK over the entire sample period. The broader frame puts the 2020 estimates into appropriate context as being the product of early-stage academic research.

Finally, the fact that the estimated CRISK is often negative and fluctuates from negative to positive over the sample period may hold some lessons on the nature of climate risk in the banking sector. Banks are intermediaries; as such, they may be well positioned to benefit from transition risk as they channel resources to those industries that are adapting to a low-carbon economy. Banks’ fundamental role as intermediaries may actually work to limit their overall climate-related financial risk.

Conclusion

All good research raises more questions than it answers. The present paper does that by rigorously exploring an important economic question. Measuring systemic, climate-related financial risk is important and should receive more attention. Putting quantitative discipline on the problem will, over the long haul, improve our understanding of climate risk and its economic impact. At the same time, we must recognize that we are at the earliest stages of understanding — let alone measuring — climate-related financial risks. Estimates of climate risk from this and related research should not be taken as an accurate or incontrovertible measure of climate-related financial risk. The available data and methods are too new, untested, and imperfect. We should continue to learn from this research while at the same time underscoring the significant conceptual and measurement challenges that remain.