Introduction

Each year, the Federal Reserve conducts a stress test of the nation’s largest banks. The results directly determine their capital requirement. When people hear about the stress tests, they naturally think that the stress test results are driven by measurable, concrete factors that contribute to a bank’s risk profile such as exposures to commercial real estate loans or complex financial instruments. While those things matter, the Federal Reserve’s projections for revenues and expenses also play a critical role. In 2024, projected non-interest expense was the single largest driver of the stress test results for Forum members. Projected expenses are, quite unfortunately, one of the least transparent aspects of the annual stress tests. Moreover, expenses are not themselves drivers of risk in the banking sector that should have a first-order impact on capital requirements. This year’s stress test sheds light on the exceedingly opaque nature of the stress tests that contribute to unnecessary and costly volatility in bank capital requirements. The stress tests would be significantly improved with increased transparency as well as a re-evaluation of the process for projecting revenues and expenses in the stress tests.

Expense Projections and the 2024 Stress Tests

Each year, the Federal Reserve’s stress test projects loan and securities losses over a three-year horizon for the nation’s largest banks. These projected losses are driven by the specific exposures that each bank has on its balance sheet as well as the severely adverse stress scenario that is hypothesized by the Federal Reserve each year. A bank with large exposures to a sector that the Federal Reserve decides will be subject to a large shock in the stress scenario will experience elevated projected losses. These losses should be the key driver of risk that would then inform the results of the stress test.

Because the stress scenario is assumed to unfold over a very long, three-year, horizon the stress testing procedure must also project and account for revenues and expenses. Over a three-year period, one can’t simply assume that revenues and expenses are zero as net income before loan loss provisions (revenue less expense) adds to the capital base that is eroded by any projected loan and security losses.

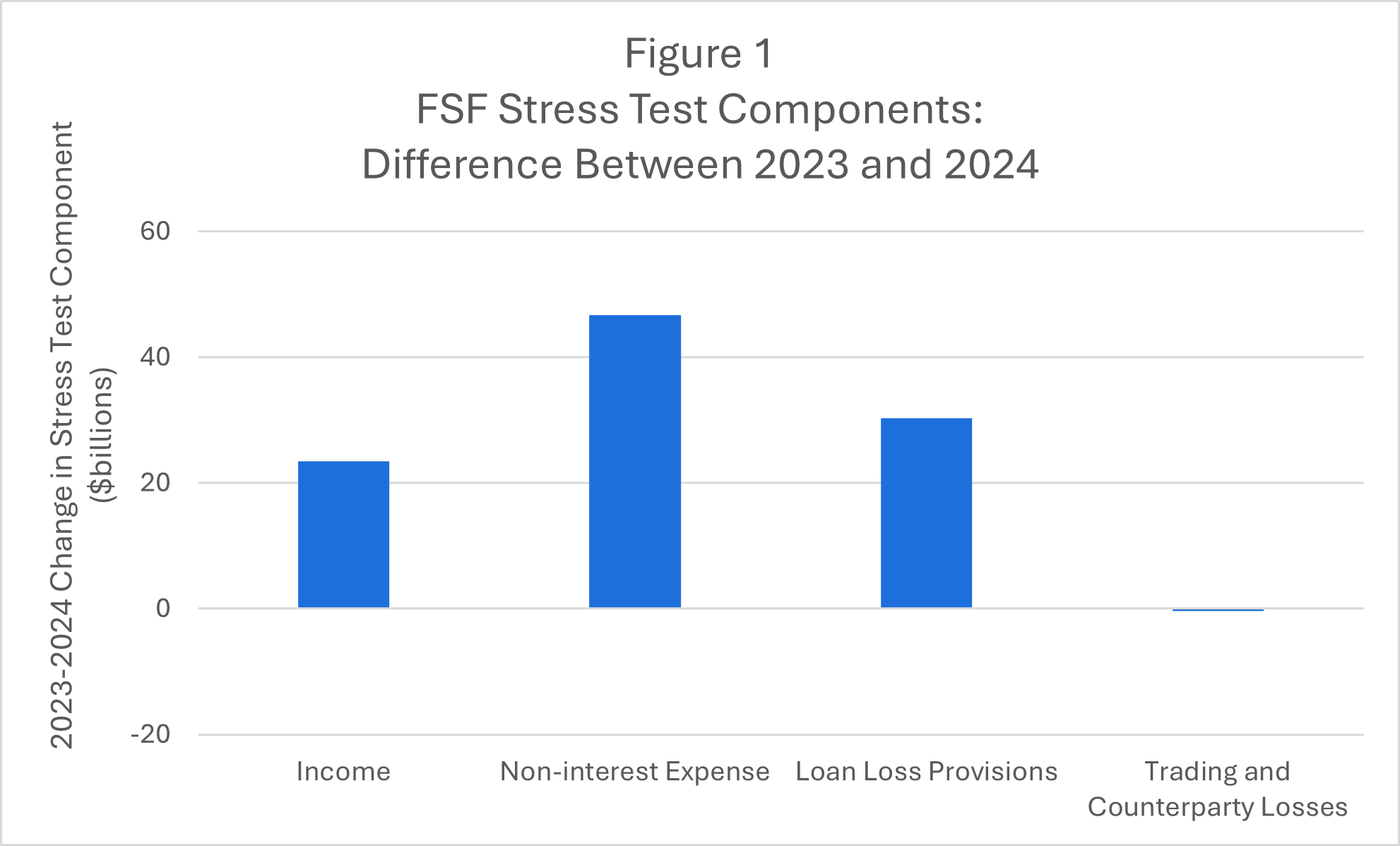

Below, we show the change between 2023 and 2024 in the most significant components of the stress tests: income, non-interest expense, loan losses, and trading and counterparty losses.

Source: Federal Reserve Board Stress Testing Disclosures: 2023-2024

As can be seen in Figure 1, the single largest change in the key stress testing components was a nearly $47 billion increase in non-interest expenses. In addition, income rose by roughly $24 billion while loan losses (provisions) increased by roughly $30 billion, and trading and counterparty losses were effectively unchanged.

The data in Figure 1 speak to the significance of expense modeling and projections to the stress tests. Since Friday, June 28, 2024, Forum members have publicly announced that the stress tests will increase their stress capital buffer, or SCB, by roughly 0.4 percent on average. Much of this increase can be traced directly to the increase in projected non-interest expense displayed in Figure 1.

Given that a bank’s SCB is an integral component in its overall capital requirement, and that capital requirements at banks have a measurable impact on the broad economy, at this point, we should pause and think a little bit about exactly what is going on here. First, what exactly are “non-interest expenses” and second, do they really have any information content about a bank’s risk level that should inform its capital requirement?

Non-Interest Expenses Explained

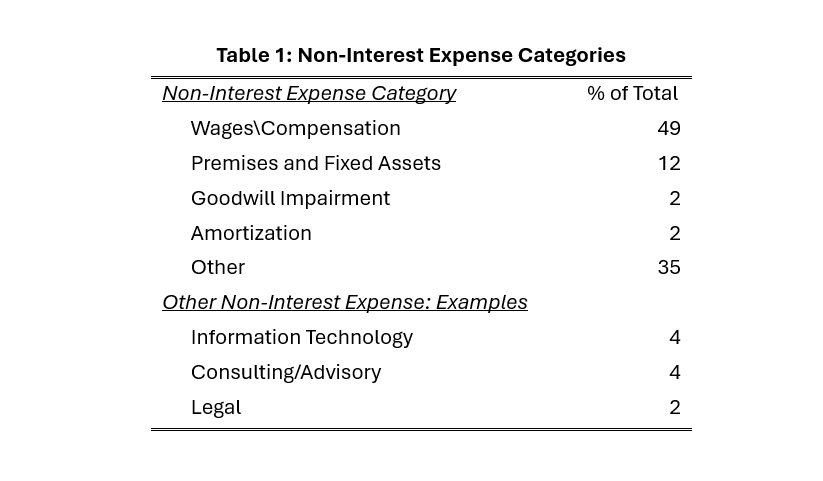

As the name suggests “non-interest expenses” are those bank expenses besides interest payments made by banks on their deposits and other debt instruments. As an aside, interest expense is typically not broken out separately, but is considered as part of “net interest income” (interest income less interest expenses). Table 1 below shows the main components of non-interest expense as detailed in Federal Reserve research and also provides a few illustrative examples of non-interest expenses.

In light of the constituents of non-interest expense, is there any reason to expect these expenses would be a driver of risk in the banking sector? Any reasonable analysis would clearly indicate that this is not the case. Accordingly, it is hard to understand how the single largest driver of the 2024 stress test results could stem from an increase in costs associated with things like consulting fees, real estate expenses, and the like.

Finally, one last conceptual issue with projected non-interest expenses. Apparently, the stress tests assume that non-interest expenses will rise in a stress event. But roughly half of non-interest expense is accounted for by wages. In a period of financial stress, wages are likely to fall and not rise as financial activity grinds to a halt. Even if wages don’t rise, the idea that they would increase markedly is counter to any standard economic theory of supply and demand in the labor market.

Stress Testing Opacity and Non-Interest Expense

As discussed, non-interest expenses are projected in the stress tests due to the very long, three-year, horizon of the hypothesized stress scenario. How exactly then are these expenses projected? The short answer is that nobody, except Federal Reserve staff, knows the answer to that question. Moreover, if loan or security losses are projected to increase, one can at least observe whether a bank has a rising exposure to those assets or whether the scenario posits a particularly challenging economic environment for such assets – as in sharply declining commercial real estate prices. In the case of non-interest expenses, what specific economic indicia would portend sharply rising wages, consulting fees, real estate costs, or IT costs? These sorts of costs are largely unrelated to financial and economic risk, suggesting that the related projections in the stress tests are largely discretionary without being tied to any clear indicators of risk or distress. The resulting projections then naturally result in overly volatile stress test results unrelated to financial risk.

On June 26, 2024, the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Monetary Policy held a hearing entitled “Stress Testing: What’s in the Black Box.” In that hearing, the Forum and several other experts testified on the concerning nature of an opaque regulatory process that levies capital requirements using non-public, quantitative models that cannot be reviewed, examined, or audited by the public. This year’s round of stress tests adds another clear data point underscoring the urgent need for greater transparency in the stress tests. When stress test results and resulting capital requirements are driven by opaque projections for expenses largely unrelated to financial risk, the entire basis for stress testing is called into question.

Conclusion

The increased severity of this year’s stress test results are being driven by opaque projections for certain expenses that are not generally tied to any reasonable notion of financial risk. As a result, we are witnessing an injection of regulatory volatility via undisclosed and opaque models into regulatory capital requirements that do not serve the public interest. The stress tests should be reformed to be more transparent to the public so that policymakers and the broader public can evaluate whether the stress tests reasonably and realistically assess the riskiness and capital adequacy of our nation’s largest banks.