Introduction

Recently, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) issued a press release indicating that it had made substantive technical changes to the calculation of the GSIB score for EU-based Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIBs). According to news reports, the effect of the change will lower the GSIB score and related capital surcharge for some European GSIBs, including one European GSIB that saw its GSIB score increase in 2021 to a level that, absent any changes, would have resulted in an increase in its GSIB capital surcharge. The announced change was rather unusual because it was announced via a press release and without any period of notice and comment. Generally, substantive changes to internationally agreed-upon regulations, such as the GSIB surcharge, are only changed after the public is provided with an opportunity to review and comment on the proposed change. By way of example, in the same press release, the BCBS discussed its climate-related guidance and cryptoasset capital rule proposal, both of which were put out for extensive notice and comment.

The Basel Committee’s Change to the GSIB Score for European GSIBs

The specific change announced by the BCBS will treat loan and related exposures of EU-based GSIBs in different EU countries as though they were exposures within a single jurisdiction. This change is impactful for EU-based GSIBs because one of the GSIB score indicators reflects “cross-jurisdictional activity” and greater cross-jurisdictional activity results in a higher GSIB score and surcharge. Before the change was announced, a GSIB based in, say, France would recognize a loan made to a company headquartered in Greece as a “cross-jurisdictional” exposure. Post the change, this exposure is not counted as a “cross-jurisdictional” exposure. More precisely, only one-third of the exposure to Greece would be counted as cross-jurisdictional. The BCBS press release points to the existence of an EU banking union as the primary rationale for this change. While the goal of a banking union is laudable in principle and provides some support for treating exposures within the EU similarly, a banking union is not tantamount to a single, overarching federal government with identical property rights, laws, and, importantly, bankruptcy codes that would determine the disposition of assets in the event of an insolvency.

Broader Issues with the GSIB Surcharge and Its Application in the United States

The recent announcement by the BCBS raises several important questions about the GSIB surcharge and its application in the United States. This recent action makes clear that international regulators are willing to revisit the GSIB surcharge and make targeted adjustments as conditions warrant. At the same time, this specific change announced by the BCBS is rather narrowly focused and only benefits EU-based GSIBs. All other GSIBs, including U.S.-based GSIBs, all of which are Financial Services Forum members, will see no change to their GSIB scores or resulting capital surcharges. It has been long recognized by U.S regulators that the GSIB surcharge should be reviewed and targeted adjustments should be made if the outcome of the review shows changes are warranted. Indeed, the Federal Reserve’s final rule – published in 2015 – recognized the need for such ongoing review and re-calibration. Specifically, the Board stated that “to ensure changes in economic growth do not unduly affect firms’ systemic risk scores, the Board will periodically review the coefficients and make adjustments as appropriate.”

The process resulting in the recent change to the GSIB score methodology for EU-based GSIBs is highly problematic because it has not been done within the context of broader and more holistic review of the framework that would include all major jurisdictions including the United States. The entire rationale for international bodies like the BCBS is to ensure a degree of consistency in international bank regulation. Making changes to the GSIB score methodology for some jurisdictions without even considering changes for other jurisdictions is contrary to the primary motivation for international capital agreements. Some might argue that the recent changes are those of the “Basel Committee” and do not reflect the views of the Federal Reserve. Of course, the Federal Reserve is an influential member of the Basel Committee. Also, the Basel Committee is a consensus-driven body and while we can’t know all of the inner machinations of that body, it is certainly the case that the Federal Reserve was aware of and took part in the deliberations that resulted in the changes for European GSIBs.

Some may argue that the recent changes are not relevant for Forum members because they are subject to a different (and more stringent) version of the GSIB surcharge and the changes will have no effect on their capital requirements. This reasoning is severely misguided. All Forum members compete with their European peers at all times and in all places. As we have previously discussed, U.S. firms are already disadvantaged relative to their European counterparts due to more stringent and costly capital requirements. The recent changes that will lower the GSIB surcharge for some European GSIBs only further exacerbates existing and substantial competitive inequities on the capital front.

Also, the manner in which the change for European GSIBs was implemented is noteworthy. While there was mention of a review of the methodology that applies to European GSIBs, there was no specific and detailed proposal that was provided for public comment and review. Even now, the specific change to the GSIB methodology for European Banking Union (EBU)-headquartered GSIBs is still unclear because, as the BCBS put it, “in due course, the EU authorities will publish a more detailed description of the methodology and requirements for relevant EBU-headquartered banks to publish the cross-jurisdictional indicators needed to calculate the parallel set of scores.” Had this change been publicly communicated with a proposal and the standard notice-and-comment process, a variety of stakeholders could have weighed in on the proposed changes, including the need to consider broader changes beyond the EU. Such comments could have informed the view of the BCBS and could have resulted in a more fulsome review of the GSIB score methodology with the BCBS as well as its member countries.

Chronic and Acute Problems with the GSIB Surcharge in the United States

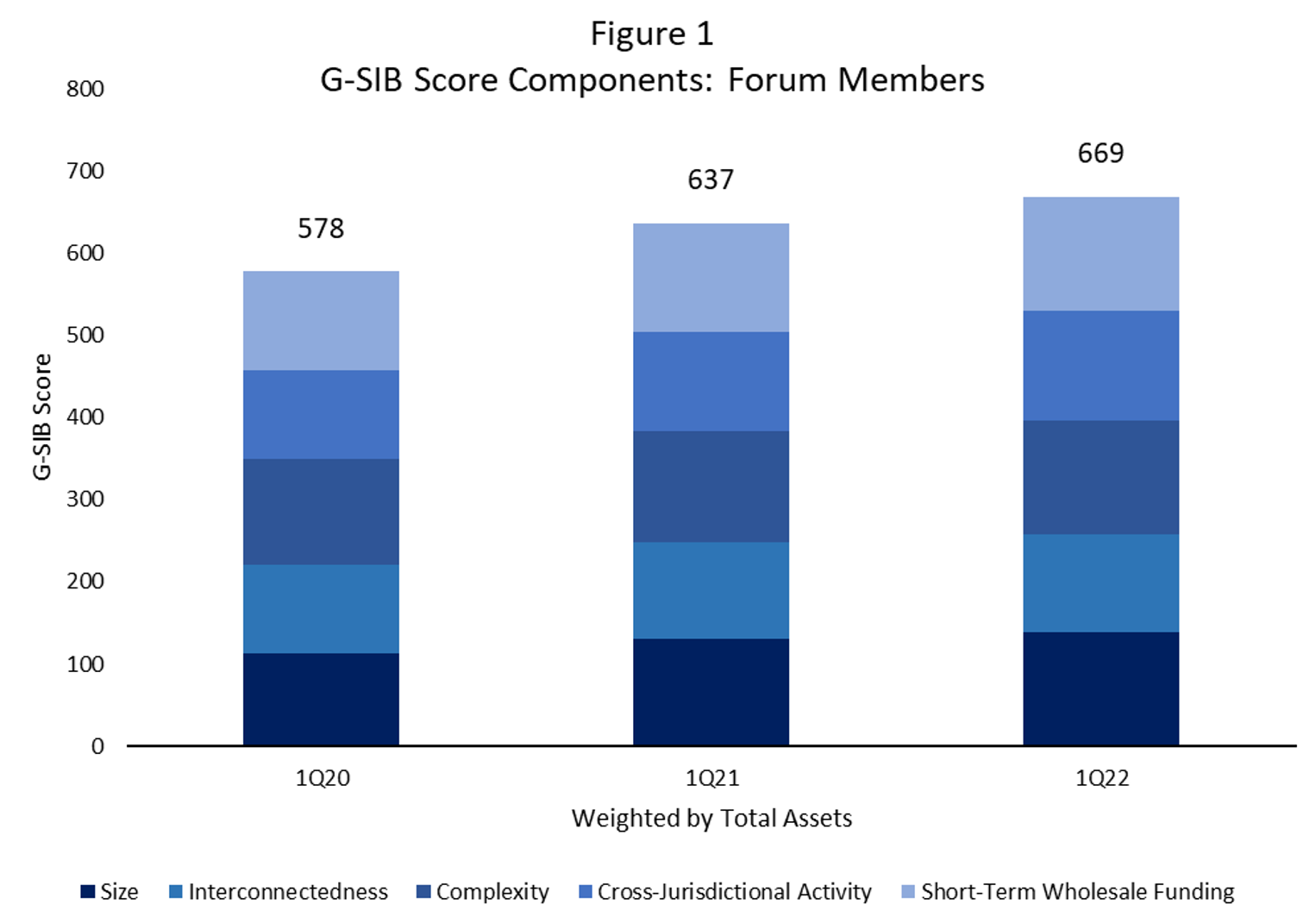

Further, the U.S. GSIB score and surcharge are plagued by well-documented chronic and acute problems that are long overdue for redress. On the chronic front, as we have discussed, the GSIB surcharge fails to account for economic growth (a problem that does not plague the non-U.S. version of the GSIB surcharge) so that Forum members are subject to higher and higher capital surcharges as the economy grows. On the acute front, as we have also discussed, the massive macroeconomic stabilization policies of the Federal Reserve and the rest of the U.S. government have resulted in an unprecedented increase in the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet that continues to put upward pressure on Forum member GSIB scores and surcharges despite the fact that an increase in holdings of bank reserves and U.S. Treasury securities (which have funded the government’s fiscal COVID response) actually reduce rather than increase systemic risk. Figure 1 below documents the large increase in GSIB scores that has taken place during the COVID pandemic, underscoring the severity of these chronic and acute problems. Accordingly, there is every reason to engage in a review of the U.S. GSIB score methodology. Making changes to the GSIB score methodology for some firms and not others is even more problematic in light of the well-documented and serious deficiencies of the U.S. methodology.

Source: Federal Reserve Y-15

Conclusion

Recently announced changes to the GSIB score methodology for EU-based GSIBs agreed by the BCBS and its members further weakens the competitive standing of large U.S. banks relative to their foreign competitors. Moreover, the GSIB score methodology is ripe for reconsideration in the U.S. Making changes to international banking regulations in an uncoordinated manner erodes the value of international standard-setting bodies such as the BCBS. The Federal Reserve should quickly move to open a review, subject to public review and comment, of the U.S. GSIB score methodology to ensure that international financial regulation is globally coordinated and promotes a healthy and competitive playing field for all.