It is expected that bank regulators will soon release a proposal to raise capital requirements for the largest U.S. banks. The proposal is expected to increase capital for the largest U.S. banks substantially, by as much as 20 percent. All of this comes at a time, however, when the largest banks are already exceptionally well capitalized. Indeed, Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell has characterized the capital level of U.S. GSIB banks – all Forum members – as being at “multi-decade highs.” More recently, the Federal Reserve Board in its Financial Stability Report found that “as of the fourth quarter of 2022, banks in the aggregate were well capitalized, especially U.S. global systemically important banks.” In light of the current strong capital and resilience of Forum members it is difficult to understand the zeal to continually raise capital standards for U.S. GSIBs. In this blog we discuss some of the flawed arguments for excessively raising capital and some of the consequences that would come from additional and unnecessary increases in Forum member capital requirements.

Confusing Levels with Changes

A common rational for increasing capital requirements is some form of “strong banks make for a strong economy,” which essentially argues that banks with strong capital positions are in a good position to lend to and support the economy. There is, of course, some truth to that point of view, but no one should confuse the statement that “banks with high capital promote a strong economy” with “banks with higher capital promote a stronger economy.” As a matter of pure logic, the first statement in no way implies the second. More importantly, as in almost all things in life, more is not always better. The examples proving this fundamental truth are too numerous to list and come from all walks of life. A sea wall of modest height along a beach stops erosion and protects the coast from severe storms. Building the sea wall to several stories is prohibitively costly, offers little additional protection, and creates an eyesore that blocks the view of the ocean for everyone. Every economy needs to save to finance investment and grow, but too much savings in an economy thwarts consumption and places a drag on growth. Simply put, you can indeed have too much of a good thing and striking appropriate balance is paramount.

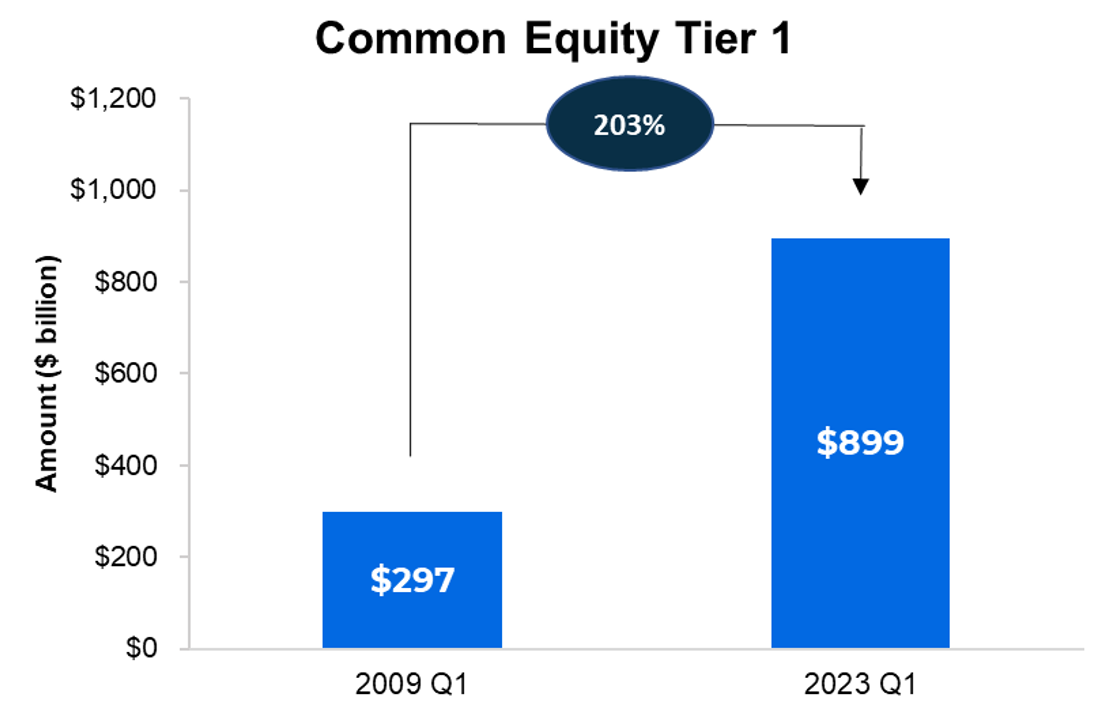

In the context of capital, the right analytical framework is to consider the marginal benefits of increasing capital. Capital, like almost everything else, is subject to the law of diminishing returns. Every additional dollar of bank capital increases bank resiliency, but the next dollar of capital always improves resiliency by less than the previous dollar. At some point you hit the point of “enough is enough” because additional capital adds very little resilience while exacting a cost to the economy in terms of higher borrowing costs and reduced credit availability. U.S. GSIBs have tremendously increased high-quality capital by more than a factor of three in the past fifteen years. As shown in the figure below, common equity capital for Forum members now stands at roughly $900 billion. When evaluating whether more capital will improve the financial system, one has to begin with the current level of bank capital and ask – in light of the current high level, will an increase in capital be beneficial?

Source: Federal Reserve Y-9C

Thankfully, economists have been actively considering this issue for some time. A recent study by PwC examined the academic literature on the “optimal” level of bank capital, finding that existing and already high levels of bank capital at the largest U.S. banks are in line with the findings of academic economists. As stated by the authors: “the optimal capital range is 12-19.5%, with an average of 15.5%. This figure aligns closely with the actual tier 1 bank capital ratios of 15.5% and 15.2%, as of the fourth quarter of 2021 and 2022.” A blanket pronouncement that increasing capital is justified based on the notion that “strong banks make for a strong economy” is conceptually flawed because it confuses the argument that robust capital levels are important with the argument that increasing capital levels will be beneficial while ignoring the already robust level of capital for our largest banks. Further increases in capital for the largest U.S. banks are unnecessary and will exact an unnecessary and avoidable toll on the U.S. economy.

The Conceptual Switcheroo of “Reduced Variability”

The pending capital proposal was originally motivated by regulators in an effort to reduce the variability of capital requirements across banks while providing greater transparency. Indeed, Governor Philip Jefferson of the Federal Reserve recently gave a speech where he cited this as a key rationale for the new capital proposal.

However, addressing capital variability does not require or justify requiring banks to maintain more capital.

First, it has been reported that the capital proposal could raise capital requirements by as much as 20 percent. There is absolutely nothing about reducing variability in capital requirements that would be expected to result in a material increase (or decrease) in capital requirements. Capital variability is reduced by removing outliers that result in either very high or very low capital requirements. If both extreme highs and lows are removed, the overall level of capital should remain largely unchanged. Arguing that the main motivation for revising capital requirements is to “reduce excess variability” while those revisions are expected to increase capital by 20 percent is a conceptual switcheroo.

Second, significant variability in capital levels of individual banks is largely driven by the use of internal bank models for computing required capital. Different banks employing different assumptions in their models, rightly or wrongly, will result in differing capital requirements. The use of internal models for capital purposes is almost entirely an issue for European banks and not U.S. banks. For over a decade, U.S. bank capital requirements have been determined through the use of “standardized” approaches, which prohibit the use of bank internal models. Accordingly, there is very little scope for U.S. banks to generate variability in their capital requirements because they are largely prohibited from employing the kinds of internal models that are regularly employed by European banks. Accordingly, the goal of reducing excess capital variability must be achieved largely through the regulation of internal models employed by European banks.

The Fallacy of “Long Transition Periods”

When confronted with the clear and obvious costs of further capital increases, some respond by stating that the costs can be managed because banks will be given “a long time” to come into compliance. This argument is both incorrect and disingenuous because it ignores recent experience with capital regulation.

When capital requirements change, bank analysts and other market participants immediately assess the impact on the banking sector and hold banks to these new and higher standards. In turn, banks move expeditiously to comply with the new and higher requirements to demonstrate their overall strength and resilience. The fact that the rule allows for more time to comply as a regulatory matter is simply irrelevant.

This fact was clearly demonstrated during the earlier stages of the post-crisis Basel III reforms. Specifically, research from the Federal Reserve showed that banks began complying with the requirements for Basel III even before the Basel III rule had been finalized in the U.S. As the authors put it, “bank responses we estimate take place well before the Basel III rules started to come into force after 2014.” The importance of this point cannot be overstated. The well-documented fact hat banks were “pulling forward” new capital requirements even before the ink was dry on the final Basel III requirements clearly shows that any claim that a “long transition period” will blunt the costs of increased capital regulation is without any theoretical or empirical basis.

Conclusion

Forum members have collectively more than tripled their capital levels over the past fifteen years. The events of the past few years – whether the pandemic or the regional bank turmoil – have clearly demonstrated the strength of Forum members’ capital positions. Consequently, there is no compelling reason for a further significant increase in capital for Forum members. Moreover, regulators have yet to provide any clear or convincing case for any capital raise for the largest U.S. banks. Arguments that have been provided such as “strong banks make for a strong economy” or “the revised capital framework will reduce excess capital variability” either ignore the already robust level of capital or are at odds with the fundamental facts surrounding the planned hike in capital. Unnecessarily increasing capital will necessarily result in large costs for the economy in terms of increased borrowing costs and reduced access to credit without any significant improvement in resiliency. Finally, the notion that stretching out the timeline for compliance will ameliorate these large costs ignores well-known and well-documented realities of how quickly the financial sector adjusts to new regulatory requirements. Regulators and the public should carefully and seriously consider the level of capital for U.S. GSIBs and the economic impact of any further increases before proposing any new requirements.