Introduction

Earlier this week, the Federal Reserve held a conference to consider the state of the capital regime for large banks. The event was excellent for several reasons. First, the event openly recognized the need to review, reconsider, and reform the large bank capital regime. Fifteen years post-crisis, much of the large bank capital regime has gone unexamined and has not kept pace with the realities of the banking sector or our economy. Second, the conference engaged a wide array of stakeholders with views from academics, industry experts, and former regulators. The conference neither unapologetically rationalized the existing framework, nor reflexively argued that the entire framework was faulty. Rather, the conference took a hard, introspective look at a capital framework that was engineered well over a decade ago and asked important and tough questions about how it can best serve our economy for the future.

In this post, we provide some specific reactions to the conference that we hope can add to the public conversation about the future of the large bank capital regime. For the sake of brevity, our reactions are targeted and limited. Interested readers are invited to check out the entire conference on YouTube for the full presentations and discussions.

Leverage Reform

One panel considered the case for leverage ratio reform. The panel broadly recognized the need for leverage reform given the significant changes to the economy and financial system since the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR) was introduced in 2015. Namely, post-COVID the level of bank reserves and U.S. Treasuries in circulation has expanded massively, making the SLR increasingly binding for large banks. The level of safe assets in today’s economy simply was not contemplated in 2015. Consequently, leverage ratios have moved from their intended roles as “backstops” to “frontstops,” dis-incentivizing a host of important bank activities such as intermediation in the U.S. Treasury market.

One comment from the panel is noteworthy. Some commentary suggested that leverage ratios are needed because “risk-based requirements may be wrong.” This statement is undoubtedly true because all risk assessments are inherently uncertain. But the prescription that “we need leverage ratios” simply does not follow as a result. While risk-based requirements “may” be wrong, it is also the case that the capital requirement implied by a leverage ratio is “certainly wrong.” Accordingly, and somewhat glibly, two wrongs do not make a right. What then is the answer? If the risk assessments underlying risk-based requirements are uncertain and imperfect, regulators should invest time and attention to regularly review risk-based requirements in an open, transparent, and data-based manner. Constantly striving to improve a risk-based capital regime is always better than outsourcing capital requirements to an anachronistic and undoubtedly incorrect capital requirement.

The Evolution of Capital

One panel was devoted to the general question of “how did we get here” from a capital perspective. As discussed, the large bank capital regime that we have today was engineered well over a decade ago. And like most things in life, it has grown and changed over time for reasons that are, in many cases, unanticipated and unintended. Taking regular stock of the regulatory regime and asking, “how did we get here” and “does this still make sense today” is an excellent exercise that should be repeated with regularity.

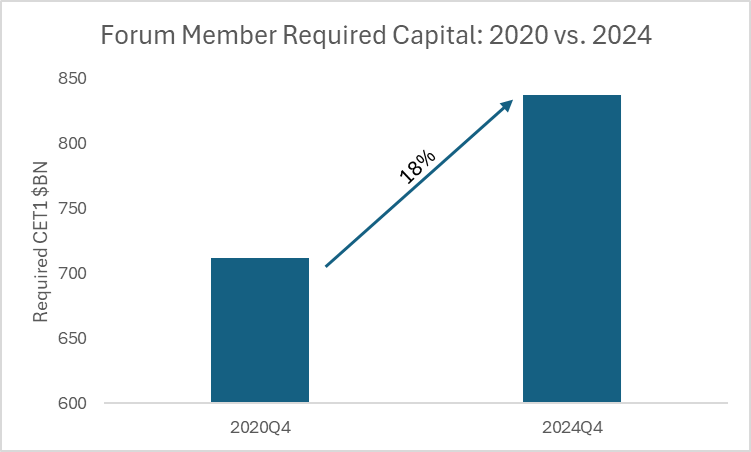

One critical point made during the panel relates to the current level of capital among large banks and the oft repeated refrain that reform should be “capital neutral.” An important fact to consider is that between the fourth quarter of 2020 and the fourth quarter of 2024, capital requirements for Forum members grew by eighteen percent, or by $125 billion. This observation is critically important to consider in the context of calls for “capital neutrality.”

As far back as 2019 Federal Reserve officials, including Chairman Powell, have publicly stated that large bank capital levels are “about right.” Against this backdrop, capital requirements for the largest banks have grown steadily. As a result, when suggesting that capital reform be “neutral” it is important to ask, “neutral relative to what capital level?” Simply calling for “capital neutrality” in an environment of steadily rising requirements is, at best, an incomplete prescription.

GSIB Surcharge

One panel was devoted to a requirement for Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIBs), the GSIB surcharge, which is an important capital requirement for Forum members. There was a clear recognition on the panel that since the GSIB surcharge was adopted in 2015, GSIB surcharges had “drifted” steadily upwards for reasons that were well-understood back in 2015. Policy inertia has resulted in a GSIB surcharge that no longer reflects any reasonable notion of “systemic risk” and is out of step with today’s banking and financial system.

Two points from the panel are worth emphasizing.

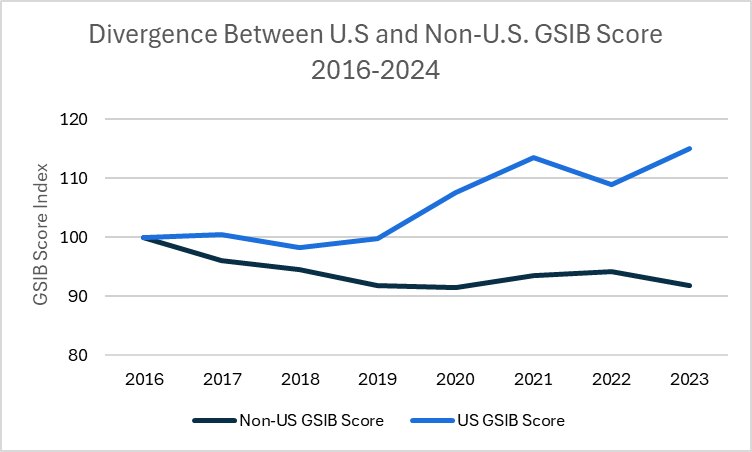

First, the U.S. is an outlier relative to the rest of the world. In 2015, the U.S. implementation of the GSIB surcharge was calibrated to be more stringent than the international standard. Over time, this excessive stringency has increased due to policy inaction. Moreover, there has been little to no discussion or rationalization of the increase in stringency relative to the international standard since 2015.

Second, the current structure and calibration of the GSIB surcharge will continue to result in mechanically rising capital levels for Forum members (U.S. GSIBs) until the framework is reformed. This is an issue we have raised in previous posts as well as a more detailed research paper. In particular, the gap between the capital requirements for U.S. GSIBs and smaller banks is wide and will continue to widen until the GSIB surcharge is reformed. Given the events surrounding the regional bank turmoil of 2023, it is entirely fair to question whether a widening of the gap in capital between U.S. GSIBs and other banks is sensible policy. Finally, it should be noted that GSIB surcharges are continuing their unabated upward march. Specifically, several Forum members will see increased GSIB surcharges beginning in January of 2026 given the mechanical and backward-looking nature of the GSIB surcharge rule. Regulators should consider halting any oncoming increases to GSIB surcharges until after the GSIB surcharge rule has been reformed.

Stress Tests

Like other elements of the large bank capital regime, the stress tests were born during the crisis under a specific set of stressful and unique circumstances. Since that time, little has been done to reconsider and rationalize the existing system. Recently, however, the Federal Reserve has embarked on an important project to reconsider and reform the stress testing process. The effort should be applauded and supported.

One issue that was discussed on the stress testing panel was the use of so-called “Pillar II” capital requirements to implement stress testing requirements as is done in the UK and Europe. In a nutshell, Pillar II requirements are essentially capital requirements that are determined through supervisory discretion with some input from the banks being regulated.

The Pillar II approach was described by some as a more nuanced and flexible approach to using stress tests to calibrate large bank capital levels. This reasoning is highly problematic. Such an approach is at direct odds with the reform program that has already been announced by the Federal Reserve to provide more transparency on the stress tests. Also, a Pillar II approach preserves, and indeed would codify, a key flaw with the existing stress testing program: opacity. Capital requirements that are prescribed by supervisors based on their own private view of a bank’s resiliency, no matter how well informed, are inherently opaque. And opaque regulation invites policy volatility as policy views change with changes in political and regulatory leadership. Finally, even if banks themselves have some insight and agency in the setting of such Pillar II requirements, the public is kept completely in the dark. As a result, the information provided by the stress test would become significantly less informative and useful to the public.

Conclusion

This week’s capital conference at the Federal Reserve marked an important step forward in modernizing the large bank capital regime. In the marketplace of ideas, this conference provided much food for thought that will surely prove helpful to regulators as they chart the course ahead. Now, the onus is on the regulatory community to take these ideas and move forward deliberately and expeditiously with capital reform. As this happens, regulators should continue their public outreach to assess their progress and strive to ensure safety and stability while promoting economic growth.