Introduction

In a recent blog post on the banking agencies’ Basel III Endgame proposal, Wharton Professor Peter Conti-Brown made a number of sweeping assertions about how the Federal Reserve Board should execute its mission that are inconsistent with the Federal Reserve Act and the Federal Reserve’s long-standing practice and that would substantially weaken the Federal Reserve as an institution. In this post, we examine three specific claims made by Conti-Brown and discuss how they are antithetical to both the historical practice and fundamental mission of the Federal Reserve.

The Federal Reserve is Not an Appendage of the Presidential Administration

In his post, Conti-Brown asserted that the Federal Reserve should simply approve the Basel III Endgame proposal because it (supposedly) aligns with the views of the current presidential administration. Specifically, he writes “we must resolve the question of bank capital through a political process— and the voters elected a Democratic president and his appointees to make these decisions.”

This statement appears to suggest that the Board is little more than an extension of the current presidential administration. Nothing could be further from the truth. In terms of both its monetary policy and financial regulatory missions, there is nothing in the Federal Reserve Act or in the 111-year history of the Federal Reserve to suggest that this is the case.

The Federal Reserve Board is just that – a Board comprised of seven individuals that come from the 12 different Federal Reserve districts and serve lengthy 14-year terms to insulate themselves from short-term political pressures. Indeed, the Board structure of the Federal Reserve is one of its key design features. The drafters of the Federal Reserve Act were wary of the prospect of a centralized decision-making body that was influenced solely by Washington politics. The resulting Board structure was a compromise designed to ensure, as stated in the Federal Reserve Act itself, that the Board benefits from a diverse range of views that give due regard to “financial, agricultural, industrial, and commercial interests, and geographical divisions of the country.”

The idea, however, that the Federal Reserve should act as a wing of the administration is not new, though it has been thoroughly discredited. Before 1936, both the Secretary of the Treasury, as Board chair, and the Comptroller of the Currency served as Board members. The outsized influence of administration officials on the Board has been correctly viewed as being a key source of organizational dysfunction that precipitated a series of policy blunders that exacerbated the Great Depression. The Banking Act of 1935 rectified the situation by removing both the Secretary of the Treasury and the Comptroller of the Currency from the Board.

Finally, the Federal Reserve Board’s darkest historical episodes are fundamentally tied to an all-too-cozy relationship with the administration. Both the Fed-Treasury accord that resulted in overt government control of interest rates from World War II to the end of the Korean War as well as Former Fed Chairman Arthur Burns’s infamous attempt to use monetary policy to re-elect a sitting president show just how dangerous it is to let the Federal Reserve be guided by an unquestioned allegiance to any presidential administration. Indeed, much economic research has shown that across the globe and over time, central banks that operate free from the strictures of executive political control are best able to achieve their mandates and serve the economy.

Consensus is the Norm on the Federal Reserve Board

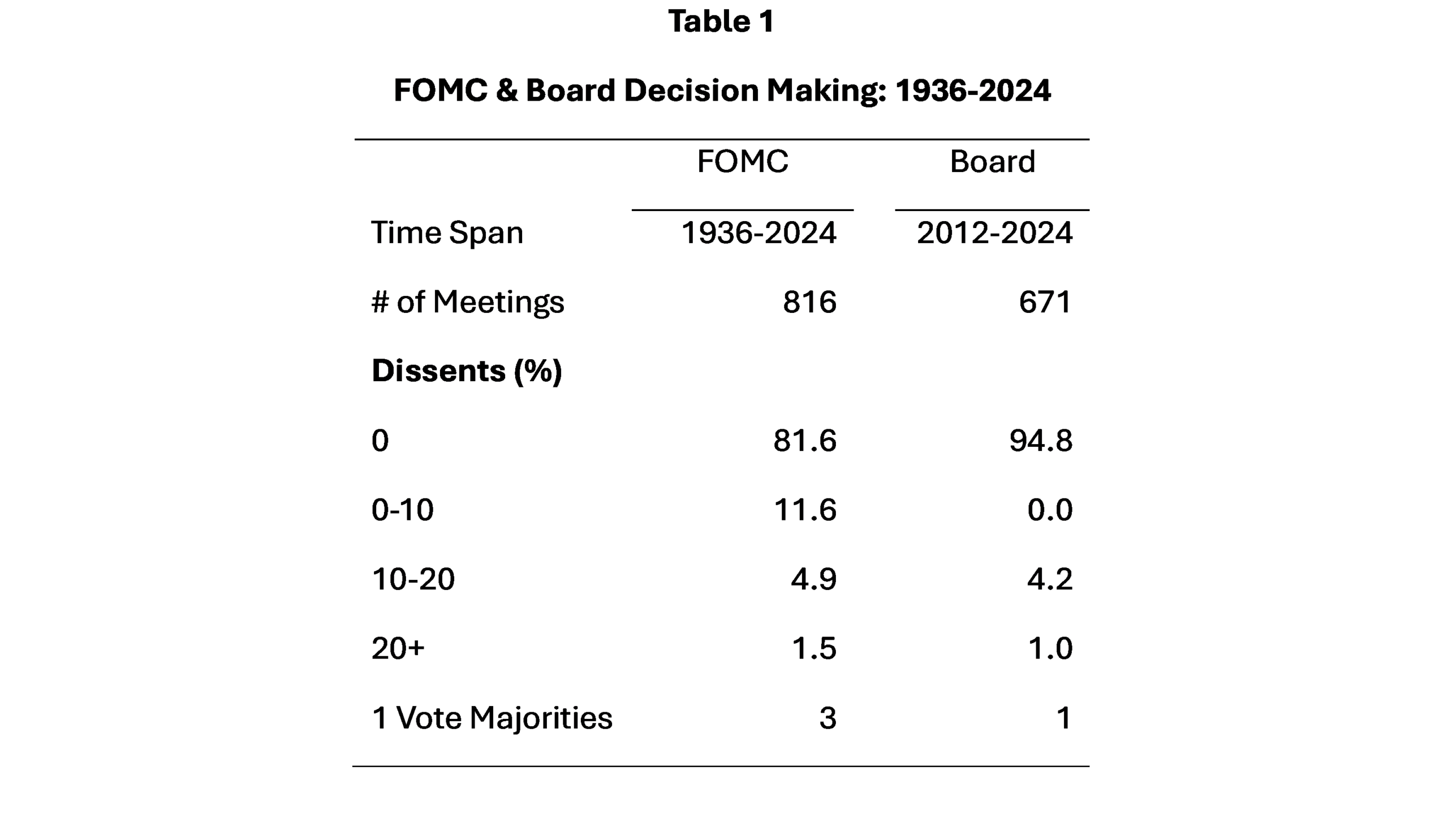

Conti-Brown goes on to suggest that the Board should operate on a simple majority wins, winner-take-all basis. Specifically, he writes “the standard that [Vice Chair for Supervision] Barr must face is the simple arithmetic of winning a bare majority of his colleagues.” Such an approach would belie the 111-year history of the Federal Reserve as a consensus-driven body. In Table 1 below, we demonstrate this point by documenting the consensus-driven nature of Federal Reserve Board votes and Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) interest rate decisions since the 1930’s.

The public data on FOMC policy decisions stretches back to 1936 while available data on Board votes only stretches back to 2012. Board votes comprise any vote taken by the Board such as a vote on rule proposals, enforcement actions, and other regulatory matters. In Table 1, we document the percentage of dissents that have occurred at each Board and FOMC vote. We analyze the percentage of dissents rather than the raw number of dissents because the size of the Board (and the FOMC) varies over time. As an example, on a full Board with seven members a single dissent would be recorded as 1/7=14.3%. Obviously, no dissent is recorded as zero percent.

As the data in Table 1 clearly demonstrate, consensus is the overwhelming norm. Of course, dissents can and do occur. Dissent is a healthy and natural part of the policy process, but most often the Board works collaboratively towards a consensus without dissent. From 2012 onwards, dissents have occurred on Board votes only five percent (5.2) of the time. Relatedly, a single vote majority on a Board vote only occurred once in 2018 when only three Board members voted on a proposal (2-1 vote). The data for the FOMC are similar. In the entire history of the FOMC there have only been three occasions on which a vote passed by a one vote majority and a single vote majority has not occurred in over 50 years (1973).

The results of Table 1 are not surprising to those who closely follow the Federal Reserve. Indeed, even a casual review of any of the memoirs of past Fed Chairs such as Ben Bernanke, Alan Greenspan, or Paul Volcker would quickly show that the Chair views his or her primary responsibility as one of building consensus on the Board rather than simply “counting votes” to get to a majority. The strong culture of consensus at the Federal Reserve is perhaps its greatest asset. It serves as a shining example of the best kind of policymaking and should not be jettisoned in favor of a strictly partisan decision-making process that yields to short-term political pressures at the cost of making long-term, durable public policy.

The Federal Reserve Board is an Evidence-Based Institution

The most egregious and dangerous assertion made by Conti-Brown is that because the “right” level of capital is a matter of debate, the Federal Reserve should simply abdicate its responsibility and do the bidding of the administration. More specifically, Conti-Brown writes “setting the appropriate level of capital is a judgment call, a line-drawing exercise that depends largely on how one tolerates and interprets risk. That very fact—that the right level of capital will not and cannot suddenly occur to all experts—means that we must resolve the question of bank capital through a political process.”

This sentiment is both extremely dangerous and completely misunderstands the approach that the Federal Reserve takes to executing its charge. First, the simple truth is that there is no substantive policy question the Federal Reserve confronts that is not subject to considerable doubt and uncertainty. What is the right level of interest rates to promote growth and stable prices? What is the best way to organize and regulate the payments system? What is the right level of bank capital? If the standard is that every time the Federal Reserve confronts a question without a concrete and indisputable answer it should defer to the administration, then the Board would indeed have very, very little to do.

Thankfully, the Board does not operate this way. Rather, the Federal Reserve, across the entire 12-region system, employs thousands of experts: economists, supervisors, lawyers, and a range of other professionals who work tirelessly to grapple with these inherently complex questions. The Board then works with these experts to formulate data-based policy that is informed by evidence that is regularly shared with the public through speeches, testimony, public reports, and rule proposals. The public – including all members of Congress, bankers, non-financial industry representatives, and public policy groups – then has an opportunity to review the evidence and provide feedback to the Board that informs the policymaking process.

This public accountability is a hallmark of informed, responsive, and responsible policymaking. As is often said, “light is the best disinfectant.” In the case of the Basel III Endgame proposal, a key concern is that the evidence, data, and transparency that has been provided to support the proposal is not in line with previous practice or the demands of such a sweeping reform. The suggestion that the Board should somehow devolve into a black hole star chamber that treats every important policy decision as a political “line-drawing exercise” is a threat to the very legitimacy of the institution.

Conclusion

The Federal Reserve Board is one of the world’s greatest policy institutions. Its reputation is well-earned from decades of transparent, evidence-based policy making that focuses on the long-term without being driven by short-term political pressure. While it doesn’t always get it right, the broad and consensus-based nature of the Board’s decision-making process is perhaps its greatest asset and should be protected at all costs from those who would rather the Board subjugate itself to the short-term whims of the political process.